Above: Many millennials bring a use-it-or-lose-it attitude to old family china, which they lack space to store or time to wash by hand.

Writer: Larry Erickson

Photographer: Duane Tinkey

You can’t take it with you.

That truism often has an even darker corollary: Nobody else wants it.

It’s our stuff, our treasures—the keepsakes of our lives and heirlooms of our forebears.

And as baby boomers are finding as they plan bequests to their kids, the answer all too often may be “No, thanks.”

‘The Albatross’

According to antiques dealer and estate-sale specialist Steve Mumma, boomers and millennials see the world differently.

“We face that difference at every tag sale,” Mumma says, shaking his head wearily. Items that were prized when he entered this business some 30 years ago are largely shunned by young adults today.

“The albatross,” he says, “is that huge china cabinet and dining room set.”

The Victorian era, apparently, just isn’t what it used to be. Instead of the large, dark brown furniture their parents inherited and preserved, young adults today are most receptive to midcentury modern.

Oh, and in addition to the china cabinet, the china has lost its heirloom luster, too. Mumma’s associate at A-Okay Antiques, Peggy Perkins, has a ready explanation: “Young people don’t want old china or glassware because you can’t put it in the dishwasher.”

Another practical reason millennials steer clear of older furnishings, Mumma and Perkins agree, is space. More live in apartments and smaller homes, so that grand walnut dining room set has no place to go.

One aspect of this is remarkably consistent between generations: Most are drawn to things from their grandparents’ era, Mumma says—boomers to the Victorian and Craftsman styles, millennials to the midcentury look.

In addition to changing tastes and space, millennials in general seem less hooked on the sentimental value in preserving pieces of the past, Mumma says.

Preserving family treasures has some urgency, too. By 2030, the U.S. population over 65 will soar by 80 percent from its level in the 2010 census. And by 2030, one in five Americans will be 85 or older, with potential heirs spread out much farther afield than in the past.

Polite Smiles

Dipping a toe into the murky waters of estate planning, I invited my two 30-something kids to scan the treasures of my life and make lists of what splendid items they would like to receive. My daughter likes a painting. Her brother? My old rocking chair and maybe a few random bits.

“OK, what else?” I asked in the uncomfortable silence. Nothing.

“But what about your great-great-grandfather’s ornamental mustache cup? What about this 1870s chair from the family homestead?”

They smiled politely.

Demographics play a role in all this, too. Families are smaller, so heirlooms have to be spread among fewer recipients. Compact pieces have a better chance of staying in the family. Photos, documents and jewelry, for example, are very personal, even intimate connections to ancestors.

Heirlooms preserved by Kent Mauck include treasures paired with photos.

A New Direction

The issue can be emotional, as retirees look at downsizing their homes with no one in sight to accept family treasures. So where does the baby boomer turn?

The primary options have always been:

- Give things away as a gift or bequest.

- Leave it for your heirs to sort out after you’re gone.

- Clear it out yourself, through sales, charity donations or the trash barrel.

Today, there’s even a National Association of Senior Move Managers, created to help seniors downsize their possessions. The group’s list of associates includes Anne Nieland in Urbandale.

Increasingly, retirees are opting to reduce their accumulations through sales, often in tandem with moving into smaller apartments or condominiums. “They don’t want their kids to have to deal with it,” Perkins explains.

The process can be heartbreaking as well as liberating.

When Mumma manages a tag sale, he discourages the client family from attending. “No crying at the pay tables,” he insists, then adds gently, “but it happens.”

Hard choices came with Kent and Shelia Mauck’s decision last year to downsize from a South of Grand home to a condo at the Plaza. With three daughters in college, long-term decisions loomed large.

“We sold 80% of the furnishings, but kept some heirlooms and collections,” says Kent Mauck, 60. Things that appealed to their daughters were put in storage for their future homes. “It’s kind of a time capsule of their youth,” Mauck says.

One clever decision was to photograph the girls’ artwork, awards and other documents in a seamless white box. “It’s their life in photography, and I can see it on my phone anytime,” Mauck says.

When Des Moines native Tenny Dewey’s parents died, he spent many weekends going through generations of accumulation. The process helped him grieve, Dewey says. Emotions ranged from excitement at the discovery of old documents to the pain of sentimental longing. “It was tough,” he says. But it helped that he had permission; his parents had told him to deal with the property in any way that worked for him, as an only child with obligations to his late parents and to his own son and daughter.

“We saved some things from the early 1900s, such as favorite pieces from a Tiffany glass collection, an Oriental rug and some furniture,” he says. His daughter selected some items; his son saved less. The rest was sold in a grand tag sale and on consignment.

Starting Early

This downsizing business isn’t all about seniors. At 36, Susan Hatten has moved four times, always into a smaller space. “Each time I’ve shed multiple items,” she says. Family artifacts and memorabilia are mostly confined to a small chest.

She recalls collections and keepsakes prominently displayed in the homes of older relatives. At her friends’ homes, however, the interest is “more feng shui, more minimalist in style,” she says. “You don’t see the collections.”

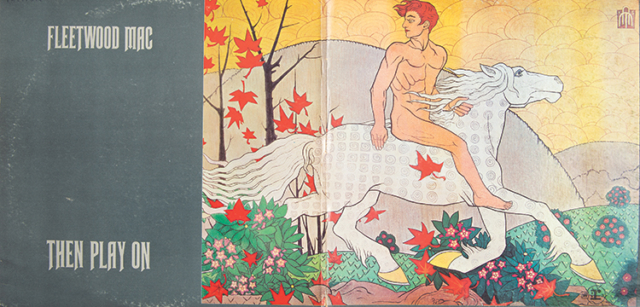

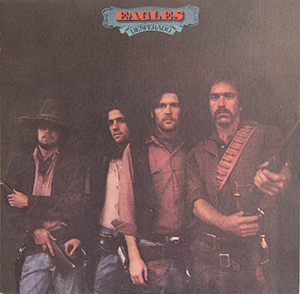

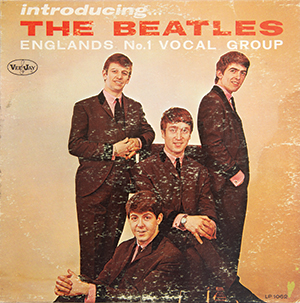

But, she adds, “we may select one of something.” For instance, her father had a massive record collection. She selected just a few album covers and displays them as art. Similarly, her parents received a spectacular wine set as a wedding gift; Hatten kept only the decanter, which reminds her of them and their home without taking up much space in hers.

Hatten says she and some of her friends have honored ancestors by using pieces of their collections and clothing “that fit our lifestyle, and that you can tell a story around.” So an article of her grandmother’s clothing “that represented her in my mind was made into something that I would wear.”

Consider a blazer from a grandfather’s closet: “Why not have a clutch made out of it and carry that to remember them?” Hatten asks.

Another thought, she offers, is to photograph “legacy pieces” and print them in a “memory book,” a service available on multiple websites and social media platforms.

On the Other Hand

Of course, there are always exceptions. At 59, architect Michael Simonson is still collecting on a grand scale. In 2005, he was able to buy his grandmother’s family farm in the wooded hills of Pennsylvania.

“I grew up hearing stories about life there,” Simonson says. His ancestors acquired the property in 1799 from a nephew of Daniel Boone.

Since Simonson bought it, he says, “it’s had a proper restoration—it’s a museum, like walking back in time.” That effect is enhanced by purchases of antiques appropriate to that bygone era and to that region of Pennsylvania.

Relatives had committed oral histories to text and created a catalog of the family’s personal property that has found its way back to the farm, including a spinning wheel, documents, dishes and textiles.

Simonson visits the farm about once a month—“I have a whole set of friends there,” he says—and admits he wonders what will become of it all. His advice to anyone with heirlooms—or farms—to share: “Observe who might have the interest and the wherewithal to maintain it.”

“I think about that.” He pauses, then adds, “I have a nephew who might be interested.”