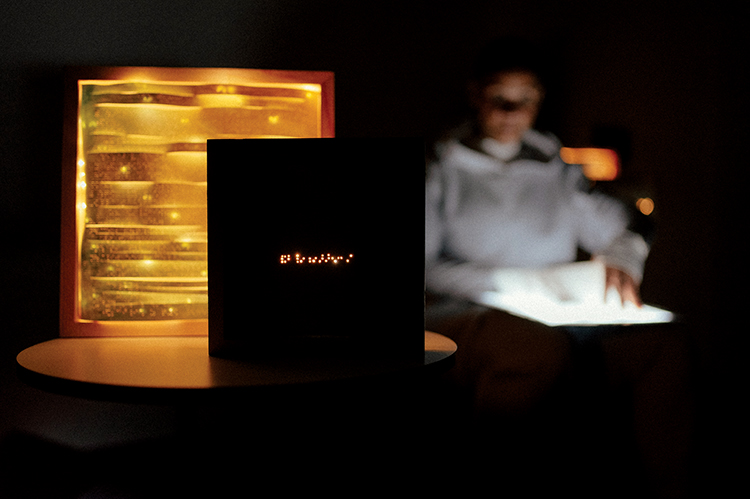

To create this piece, Jill Wells used a light pad and clear Braille labels. Underneath is a 3D black plastic butterfly.

Writer: Lisa Rossi

Photographer: Janae Gray

When Jill Wells is painting a mural, she can be up to 70 feet in the air. There’s traffic moving below her. It’s loud.

And then “things just go quiet and become really peaceful,” says Wells, a multimedia artist and muralist as well as a mentor to underserved artists. “You kind of forget you’re not touching the ground. You are in the air.”

Wells’ artwork is represented in permanent collections around the state, including at the Evelyn K. Davis Center for Working Families and Disability Rights Iowa in Des Moines, and Public Space One and the University of Iowa in Iowa City. To date, she’s created eight large-scale public works. Best known for her colorful narrative paintings, her work investigates “race, history, stereotypes, accessibility and human experiences,” according to her website.

Executing a mural is “extremely physically labor-intensive,” she says, an endeavor that expands her “mental and physical limits.” And lately, Wells, 41, is pushing the limits of the senses, delving into a new future of public art that will incorporate universal, multisensory design, so that anyone, regardless of ability, can experience her creations. That means art that could be moveable for different heights and abilities, has auditory descriptions, and is accessible via touch.

“She is paving a new direction for public art,” says Daniel Van Sant, director of disability policy at the Harkin Institute, where Wells is a fellow. “The hope is all art is inclusive and universally designed.”

This 2020 work shows a combination of three pieces that are digitally overlaid and projected over the artist’s body. The blend of images includes an oil painting atop the Braille found on the Americans With Disabilities Act, a 3D wall tile, and the words “feel, heard, love, seen.”

Dublin Mural

Recently, Wells took her talents to Dublin. She embarked on the project “Dublin LOVE Mural” with her friend, Dublin street artist Chelsea Jacobs, after being inspired by the messages of the Harkin Summit she attended in Belfast in June. The summit focused on helping people with disabilities to achieve their career goals and aspirations.

Together in just six hours, Wells and Jacobs created a mural that incorporated a portrait, lettering and other visuals. The word “Love” is spelled in Braille first and English second, in acrylic paint on the wall. The mural represents “disability awareness, advocacy, the LGBTQ community, education of languages and localities,” Wells says.

The Dublin mural sparked questions about Braille among the people watching it go up, underscoring the power of public art to “have these conversations, to potentially have an intervention for education,” Wells says.

“It’s not a piece where an individual who’s living with blindness can feel and discover exactly what’s on the surface, but my hope is if somebody gives them an auditory description, then they feel represented, seen or heard,” she adds.

Jill Wells, “Black Butterfly” (2022), a baby grand piano with acrylic, oil epoxy, LED and plastic 3D butterflies. The piano is installed at Mainframe Studios and is available for anyone to play.

Experiential Exhibit

In Des Moines, her multimedia art exhibition titled “Feel” was on display at the Plymouth Gallery at Plymouth Congregational Church in May and June. It featured 2D and 3D artworks, which invited viewers to experience them through listening to auditory descriptions of the works, feeling the works (including the Braille pages of the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act), and seeing the LED lighting and visuals. Some of the works from that exhibition were flown to Ireland for the Harkin Summit.

By taking visual art and making it “tactile and inclusive and accessible,” Wells reminds people of something that is often ignored in the disability rights movement, which typically focuses on issues such as access to voting, employment, health care, education and housing, Van Sant of the Harkin Institute says.

“True inclusivity is also about those fun, beautiful things in life,” he says. “For us, that’s something we want to highlight—creating an accessible and inclusive world, access to arts and fun.”

Inviting viewers to touch artwork has resulted in some pieces getting “knocked around,” but Wells says she was “willing to take that risk for the greater good to see if this would be successful, to see if I could replicate it. I want to continue to work with Braille and engage other senses with my artwork, and touch is a big one.”

Part of her pursuit of arts inclusivity is rooted in the experience of her brother. When he was 18, he suffered an arteriovenous malformation rupture, which causes blood to hemorrhage in the brain or surrounding tissues. That resulted in, among other complications, the loss of his sight.

“I just can’t go back, knowing what he needs,” Wells said early last summer while standing in the middle of the “Feel” exhibit at Plymouth Congregational. “I have the ability to do something about it, so I’m going to do something about it.”

Jill Wells, “Green Wave” (2020), oil, Braille, a Braille page from the Americans With Disabilities Act, LED, pine.

Finding Her Voice

Wells began discovering her niche as an artist in high school in Indianola, when the unspoken became verbal through art projects.

Her mother is white, her late father was black, and Indianola was “not diverse at all,” Wells says. “I grew up with a lot of microaggressions, like: ‘Why do you sound white?’ And just being very aware there was nobody throughout my academic career growing up in Indianola who really looked like me, other than my sister, my brother.

“So it was just very normal … to not be aware of certain parts of yourself,” she says. “But you’re still dealing with the fact that other people are trying to figure that out about you.”

She had a good teacher who introduced her to projects to look “through a different lens or have a different perspective. And that medium encourages you to have a conversation.”

That medium was a combination of visuals and the written word. “I’m writing a story on a canvas and starting to use images that tell my own personal experience, and starting to think how images are like words,” she says.

In the forefront is a work titled “Access,” a pine box with clear Braille labels and, in the back, an LED light. The larger piece, called “Lightbox ADA Braille Page 71,” consists of a pine box, oil, paper and LED lights. Wells created both works in 2020.

First Mural

At age 19, Wells created “Running Out of Time” for Creative Visions, which depicted key male figures from African American history with a line of black men running forward, symbolizing the “running out of time,” Wells said in a 2021 TEDx talk in Des Moines.

She told the audience how her mother would not come to see the mural until it was done, at which time she told Wells that the mural site was the same place Wells’ father had died.

Creative Visions used to be a pool hall, Wells explains now, and her father was shot during an argument. He was only 22 years old. “I don’t think it was intended for him,” she says. “What I was told, he was trying to stop what was happening.”

She reflected on the coincidence during her TEDx talk: “Where my feet and my hands have been creating was the same site where my father’s time ran out?”

Learning that her father tried to stop a fight had her reflecting on how it was “a brave thing to do, the right thing to do in a situation like that,” she says now.

“Sometimes the questions we grapple with after the loss of a loved one, they are very complicated,” she explains. “For me, it answered some questions [of] who is my father? Who is this man?”

Torry Simmons, Wells’ mother, says she saw God’s hand at work in Wells’ work on the mural at the same place her father died.

“You never want to think of your husband … dying in that way. It’s joyous to know she was asked to that spot to leave an imprint of positivity,” Simmons says. “I believe that God can bring some really good things out of really bad things, even if it’s decades later.”

What’s Next

Wells’ next focus will be her work as a Harkin Institute fellow, where she will research how to inform future works focused on inclusivity.

Among her explorations will be how to make art more accessible for those with mobility issues, making it come “up or down, come in or out to you—get it where you need to be,” she says.

“I’d like to continue to work towards all the senses,” she says. “I feel like we are living in that day and age. We have all these immersive and augmented realities. … I don’t see it really going backwards. That’s why I’m very excited about it.”