The famous neon sign has drawn generations of music fans to dance at the ballroom in West Des Moines, first under the stars and later under a ceiling spangled with lights.

Writer: Kyle Munson

Photos courtesy of First Fleet Concerts

A seasoned concert promoter who owns a hall in downtown Des Moines and produces events throughout the Midwest sees his opportunity to expand on the west side of the capital city. So he transforms a building at 301 Ashworth Road in West Des Moines into a new music venue.

We could be talking about Tom Archer in the 1930s or Sam Summers today. The timelines of these two music moguls span a century, both winding through the Val Air Ballroom, one of the most beloved, eclectic, rambunctious and enduring entertainment venues in Iowa.

If you moved here only recently, you may not have heard about it, because it went dark during the pandemic and closed after a final punk-rock show in December 2022. But get ready: It’s about to stage a 21st century encore. The ballroom is set to reopen on Leap Day, Feb. 29, and kick off its new life with a week of high-profile concerts. Val Air veterans will spot familiar features, such as the centerpiece 72-by-140-foot maple dance floor and the giant flashy disco ball dangling high above. But they’ll also appreciate the modern stage that looms at the southwest end of the building, double the number of restrooms and a massive new HVAC system to stave off chills or heat stroke, depending on the season.

Best of all, the iconic outdoor neon sign that hangs on the front brick facade has been restored.

Summers, 40, co-owns Wooly’s in the East Village and created the annual Hinterland Music Festival in rural St. Charles. He purchased the Val Air and its 8.5 acres in January 2022 for $1.9 million.

The overhaul’s price tag shot up to $15 million in the post-pandemic economy. Work in the basement alone added as much as $4 million. “It’s like an archeological dig down here,” Summers said last spring while standing on the dirt floor of a 5,500-square-foot basement, which will eventually accommodate a supper club.

And that dig goes deep. During the project, Summers has unearthed stories from the site’s legacy of live music, which started in 1939 when the ballroom opened on the foundation of an unfinished tire factory. In the early years, it was a summertime venue without a roof. In its Big Band and World War II heyday, couples flocked onto the dance floor to glide and twirl to the swing tunes and polkas of Glenn Miller, Lawrence Welk and other orchestral giants.

And that dig goes deep. During the project, Summers has unearthed stories from the site’s legacy of live music, which started in 1939 when the ballroom opened on the foundation of an unfinished tire factory. In the early years, it was a summertime venue without a roof. In its Big Band and World War II heyday, couples flocked onto the dance floor to glide and twirl to the swing tunes and polkas of Glenn Miller, Lawrence Welk and other orchestral giants.

Night by night, decade after decade, crowds filled the ballroom. And the beat went on.

Dance bands gave way to amplified country and rock ‘n’ roll. The Val Air hosted class reunions, corporate holiday parties, wedding receptions — even a leisure suit convention. Recent decades roared with an unusually diverse lineup, from heavy metal headbangers to traditional Mexican ballads to the infamous “Howard Dean scream,” a political flashpoint during the 2004 Iowa caucuses.

Some of the ballroom’s most frequent performers in recent years were the Kansas City rapper Tech N9ne, horrorcore duo Insane Clown Posse, and Norteño band Los Tigres del Norte, often called “the Rolling Stones of Mexico.” From prewar crooners to 21st century kickboxers and cage fighters, the Val Air has seen it all.

The ballroom has survived floods and fire. It’s one of only 19 vintage ballrooms in Iowa that still stand, according to architectural historian Alexa McDowell, who authored the Val Air’s successful 2022 application to the National Register of Historic Places. The ballroom is a “utilitarian” community venue, a “solid representation of the mainstream ballroom,” she noted. “There was nothing ever very fancy about it.”

Utility was what Tom Archer had in mind when he created the ballroom, a spot he called “the poor man’s country club.” It was a place to coax neighbors together onto the dance floor, united by the same steady beat.

Today, by sinking a post-pandemic fortune into the renovation, Summers is ushering the Val Air into its third distinct era as a cultural landmark. Like Archer before him, Summers lives close enough to the ballroom to walk to work, to the building that represents a vision not only for his career but for the entire city.

“To me, a venue is a catalyst for growth in a neighborhood,” he said. “The way we’re doing this [renovation], it’ll be here forever. That’s important to me.”

Val Era 1: Big Bands

Archer, born in 1895, grew up in southeast Nebraska, one of 10 siblings in a strict Catholic farm family. According to family lore, as long as the Archer kids followed the rules and didn’t smoke or drink, each one would receive a gold watch on his or her 18th birthday. Each of the six sons also was given a choice at age 21: a lump sum or 25 acres of farmland.

Archer chose the money to help launch his career and began dabbling in dance promotions during his military service while stationed in Wyoming.

He began his Midwest ballroom chain in 1923 in Sioux City with the Roof Garden, followed by the Arkota (“Archer” plus “Dakota”) in Sioux Falls. In 1931 in Omaha, he opened the Chermot (the second syllable of “Archer” plus “Tom” spelled backward), described as a palatial ballroom and the city’s largest.

The Val Air joined his portfolio on June 6, 1939, with bandleader Ted “Mr. Entertainment” Lewis and a crowd of 2,500. Tickets were 85 cents for men and just a quarter for women.

Archer held a public contest to name the new ballroom. “Val” was for Valley Junction, the area that just a year earlier had dropped its original railroad name in favor of the suburban sound of “West Des Moines.” “Air” was a nod to the ballroom’s lack of a roof, which enabled guests to dance under the summertime stars. (There was less light pollution in those days, but the bugs and humidity were just as apparent.) The Val Air complemented Archer’s downtown ballroom, the Tromar, which had opened in 1937.

Archer was a prominent businessman and tastemaker during the Val Air’s first era. His photo appears in Lawrence Welk’s 1971 autobiography with the caption, “Tom Archer, the famous ballroom owner, who kept pulling me out of the hole all during the thirties. A dear friend.”

Welk, Archer and other ballroom barons of the time nurtured a dance culture across the country. The Val Air held dance classes every Sunday and Wednesday that boasted a roster of more than 100 instructors, not to mention the countless couples.

Archer’s empire grew to include a dozen Midwestern ballrooms in four states. But his family life suffered; he and his first wife — with whom he adopted a son, Thomas Milton — were estranged in 1933 and divorced in 1941. Archer lived in the Hotel Fort Des Moines for years before building a home next to the Val Air on Ashworth Road with his second wife, Frances, a Des Moines native and East High graduate whom he wed in 1953.

Archer served on the board of the National Ballroom Operators Association during the ’50s, when tastes were changing and the first thump of rock ’n’ roll was growing louder. As early as 1952, the association opened the program of its annual convention in Chicago with an editorial titled, “What’s wrong with the ballroom business?” “The lush days of the World War II period are a thing of the past,” the editorial warned. “At first, just like the movie people, everyone blamed television.”

Archer included pithy business analysis of shows in his accounting books, such as this July 25, 1954, summary of Woody Herman and a crowd of 1,926: “Band worked hard, pleased most of the people. A few old regulars complained not enough danceable music. As long as Herman can do this kind of business, let them complain.”

Archer sought to grow the Val Air’s business by expanding its calendar and enclosing the dance floor beneath a tin roof in 1955 — the same year the Tromar was converted to a roller rink.

Val Era 2: Rock ’n’ Roll

According to his family, when Archer watched Elvis Presley shake his hips on ‘The Ed Sullivan Show,’ on Oct. 28, 1956, he felt the quake of cultural change and proclaimed that the end of an era was near. The brash blare of rock ’n’ roll helped transform live music into a spectator sport — not something to accompany dancing but a spectacle to watch while staying rooted in place.

Meanwhile, Tom and Frances Archer welcomed a pair of daughters who grew up in the family business. Patty was born in 1954, and Loyce in 1957.

Six years later, Tom Archer suffered a stroke on a Friday night at work and died two days later, on Aug. 4, 1963. The obituary in the Associated Press noted that “most of the nation’s great dance bands played at his places.” A newspaper headline proclaimed, “Many met their spouses dancing in his ballrooms.”

Frances, 20 years younger than her late husband, took over the business despite the challenges and chauvinists she faced as a mid-20th century businesswoman.

More recently, their younger daughter, Loyce Archer Dunbar, who retired from a career with Carnival Cruise Line, has sorted through boxes of family records and mementos to flesh out her scant memories of her father. She’s also learned more about her mother’s love for Big Band music; Frances Archer frequented the Val Air with her girlfriends before she even met her husband. “Her devotion to the art of my father’s business drew them together,” Dunbar said.

Her mother used to say that if you stood inside the Val Air long enough, you’d meet everybody in Des Moines.

One of Dunbar’s most vivid childhood memories is a fire that charred the ballroom in the winter of 1961. The Archer daughters enjoyed the skating rink the firefighters created in the parking lot after battling the blaze. Dunbar also loved to circle the dance floor with her uncle. She remembers the thrill she felt when she got to pull the string to release the balloon drop on New Year’s Eve. “New Year’s Eve has never been the same for me after the Val Air,” she said.

As the Val Air persevered into the ’70s and ’80s, it hosted rock reunion tours for the likes of Bobby Vee, Tommy Roe and Lou Christie. Ross Peeler began working at the Val Air on his 16th birthday, in 1979, and served the nostalgic baby boomers who filled the dance floor. “By the end of the evening, when we swept up the dance floor, we’d have these lint piles from people dancing,” he said. “It was just lint from their clothes.”

Patty Archer, working with her mother, lavished the musicians with hospitality, serving them homemade dinners — Swedish meatballs, pulled pork, gourmet bread, the works. She took over the ballroom after Frances died, in 1991, and managed it until the family sold it in 1996. Patty died the following year from sepsis, at age 42.

“It was hard for her to give up (the ballroom),” her sister told the Des Moines Register. “She spent her life there.”

A group of locals took over the Val Air for a while until it was sold in 2003 to Pedro Zamora of Detroit, whose Zamora Live company promotes Latino concerts and entertainment nationwide. Zamora, a Mexican immigrant who founded his sprawling entertainment empire in the 1980s in the humble banquet room of a suburban Chicago restaurant, was credited with saving the Val Air from the wrecking ball. Although he didn’t build the ballroom as Archer had done or engineer a complete renovation as Summer is now doing, Zamora worked with various promoters while also producing his own shows to keep the venue active, often catering to the growing Hispanic community.

He and his contacts in the Mexican concert industry will continue to route shows through the Val Air, including one in March. Zamora last year told Billboard that he expected to stay busier than ever in 2023 by producing more than 700 shows throughout North America — dominated by Latin artists.

Val Era 3: Shuffled Playlist

Sam Summers was still a student at Iowa State University when he began his promotions career with First Fleet Concerts, a company he still leads. The first concert he staged at the Val Air was Fall Out Boy, in 2005, long before he bought the venue.

Summers also owns a third of JRS Management, a bar business he founded with his friends Josh Ivey and Rafe Mateer. Together they opened Wooly’s in 2012 in the East Village. They’ve also opened seven Up-Down “barcades,” including the one near Wooly’s and two more on the way. In all, Summers and his business partners manage a staff of about 600.

The Hinterland Music Festival, which Summers launched in 2015, now attracts 15,000 to the amphitheater on 167 acres Summers owns about 30 miles south of Des Moines. (He also farms it, harvesting hay twice each season.)

At the Val Air, VAB LLC now joins Summers’ portfolio of entertainment companies. He said the past year was a busy one, full of daunting challenges, so he looks forward to reactivating the Val Air cashflow.

Even now, the new owner sometimes feels surprised to be in this line of work. Six years ago he was diagnosed with agoraphobia, a chronic fear of open or crowded spaces. That’s not what you’d expect for a nightlife kingpin, but he seems well suited to the behind-the-scenes orchestrations of budgets and venue management.

The Val Air’s modern stage and amenities reduce the ballroom’s capacity from 2,500 to about 2,200. The new Vibrant Music Hall, which opened in November in Waukee and is operated by the industry behemoth Live Nation, can hold 3,500, but Summers is unconcerned. He can still book acts at Vibrant, he said, but the Val Air will have “more of a vibe” thanks to its unique history.

Summers hopes the Val Air will also help him expand his clientele among a broad range of music fans in the streaming economy. He can introduce younger acts at Wooly’s, divert them to the Val Air after they’re more established and feature them at Hinterland when they mature into headline stars.

The Val Air’s upgrades, overseen by architect Pete Goche, include a new insulated roof of gypsum board, foam and drywall, which contains the sound instead of letting it resonate outward as it did from the old tin roof — much to the neighbors’ annoyance. Goche and his consultants figured out how to add the three layers while retaining the original roofline and ceiling height to satisfy requirements for historic-preservation tax credits.

Summers said he’s “proud of every part of the venue.” And Dunbar, the younger Archer daughter, has given it her blessing. She retains the rights to the Val Air name but said the ballroom’s new transition “feels like it will be my final release of it all.”

After the dust settles from the grand reopening, Summers will move ahead with the second phase and add the basement supper club. He’s calling it “Tom Archer’s Poor Man’s Country Club,” a nod to a kindred spirit whose ballroom laid a foundation for his future.

“It really feels like my place,” Summers said. “What I’m investing in this place, it’ll be my place forever.”

Reopening Lineup

Feb 29: Greensky Bluegrass

March 1: Sierra Ferrell

March 5: Flogging Molly

March 6: Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit

March 7: Eli Young Band

March 8: Chase Matthew

March 16: JJ Grey and MoFro

For details and tickets, visit firstfleetconcerts.com/val-air-ballroom

Val Air Visitors

Here are just a few of the artists who’ve taken a turn on the Val Air stage.

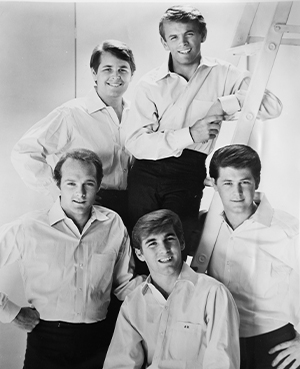

Louis Armstrong, Asleep at the Wheel, The Beach Boys, The Black Crowes, The Black Keys, Cab Calloway, Chubby Checker, The Coasters,Alice Cooper, The Crickets, Lou Christie, Jimmy Dorsey, Tommy Dorsey, Bob Dylan, Duke Ellington, The Everly Brothers, Maynard Ferguson, Ella Fitzgerald, Myron Floren, Benny Goodman, Lesley Gore, Merle Haggard, Fletcher Henderson, Woody Herman, Jan & Dean, Stan Kenton, The Killers, B.B. King, Gene Krupa, Brenda Lee, Jerry Lee Lewis, Guy Lombardo, Marilyn Maye, Glenn Miller, Red Norvo, Peter Noone, Paul Revere & the Raiders, Johnny Rivers, Marty Robbins, Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels, Sam & Dave, Del Shannon, Artie Shaw, Slipknot, The Smothers Brothers, Snoop Dogg, Rick Springfield, Hank Thompson, Jack Teagarden, Bobby Vee, The Ventures, Paul Whiteman, Lucinda Williams, Lawrence Welk, Jack White, Wilco