Grand View University’s Humphrey Center was built in 1895 with the ornate curves of the Danish Renaissance style, a nod to the Danish Lutheran immigrants who founded the university on Des Moines’ northeast side.

Writer: Michael Morain

The German writer Johann von Goethe once compared two artforms: “Music is liquid architecture, and architecture is frozen music.” If that’s true, the late Iowa architect William “Bill” Wagner produced more hit singles than anybody around.

Over the course of his career, from the 1940s till his death in 2001, he worked for the prominent local firm Wagner, Marquardt, Wetherell and Ericsson, which put its fingerprints on some of the city’s most prominent buildings: Lincoln, North and Roosevelt high schools; the old YMCA; the Scottish Rite Temple and dozens more.

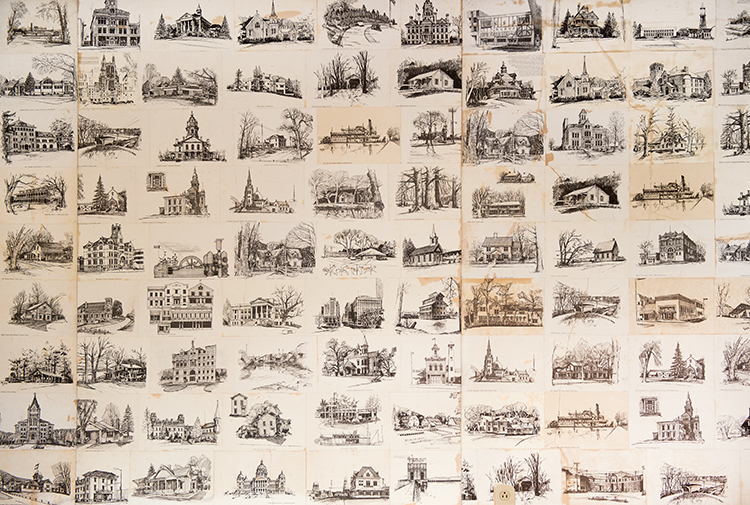

Iowans of a certain age may remember Wagner best from the sketches he drew — 360 in all — for the wall calendars the American Federal Savings and Loan Association published from 1960 through 1989. Each year’s edition featured a dozen detailed pen-and-ink sketches of notable buildings across the state, rendered in Wagner’s confident hand.

“He was always sketching. It was how he described the world to other people,” said Martha Green, who worked as a drafter for Wagner’s firm in the mid-’70s.

The firm had an extensive statewide client list, so Wagner often sketched buildings during his travels. Each sketch took him only a few minutes — and reinforced his motivation to save the state’s best old buildings for the ages.

Known as Iowa’s “father of historic preservation,” Wagner championed the cause decades before the Legislature established tax credits to fix up and maintain old buildings. His personal list of projects included Terrace Hill, Salisbury House, the courthouses in Adel and Marshalltown, and the relatively humble homes of famous Iowans like Carrie Chapman Catt, Mamie Doud Eisenhower, Herbert Hoover and the Wallace family.

Wagner helped found the Iowa Society for the Preservation of Historic Landmarks and for years organized bus tours to many of the state’s architectural highlights. Over the years, he won many state and national awards, including a fellowship from the American Institute of Architects.

And everywhere, he sketched — in Iowa as well as Australia, China, India, Japan, the Soviet Union and across Africa and Europe. Sometimes he painted watercolors, too, to tuck in with his annual Christmas letters. He also made wedding rings for his friends, including Green and her husband, Jack Porter, another preservation advocate.

“Bill was a renaissance man — architect, painter, jeweler, historian,” Porter said. “He did so many things other than architecture.”

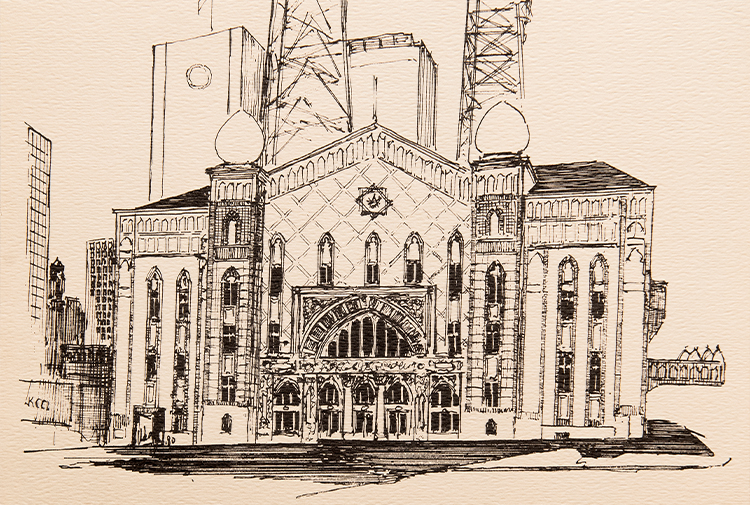

With 4,200 seats, the Za-Ga-Zig Shrine Temple was one of the world’s largest theaters when it was built in 1927 at 10th and Pleasant streets. It became the KRNT Theater in 1946, hosted local and national acts into the early 1970s and was torn down in 1986.

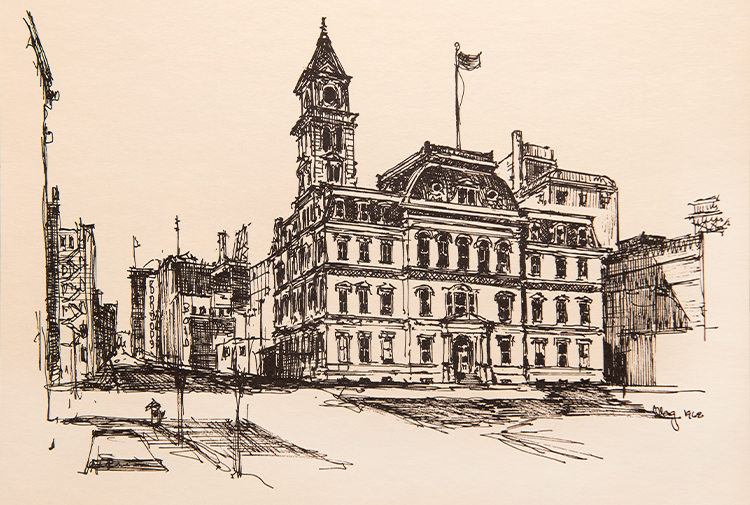

The Old Federal Building at Fifth and Court avenues was built in 1871 to house the U.S. courthouse and post office. Locals fought hard to save it a century later, but a wrecking ball demolished it in 1968. For years after, “Remember Old Fed” became a rallying cry for historic preservation.

The 1850 home of the James Jordan family on Fuller Road in West Des Moines served as a stop for freedom seekers along the Underground Railroad. It’s now a museum, owned and operated by the West Des Moines Historical Society.

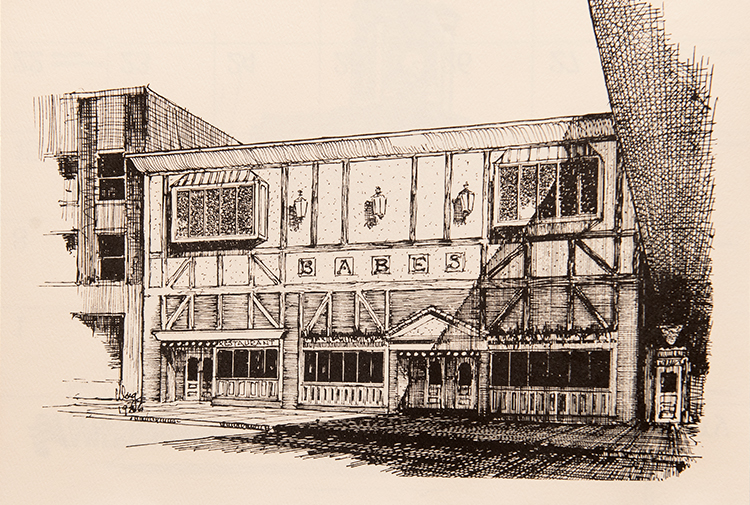

For more than 50 years, Alphonse “Babe” Bisignano presided over his namesake restaurant on Sixth Avenue. It evolved from a taproom into a full-service Italian eatery until it closed for good in 1991.

The Wagner Collection

After Bill Wagner died, in 2001, his family donated most of his sketches, drawings, paintings and books to Dallas County, which opened a permanent display in 2008 at the Forest Park Museum on the south edge of Perry. The museum also houses his collection of presidential autographs, dating back to James Monroe.

Under a grove of oaks out back, visitors can step into the old scale house (weigh station) that Wagner relocated to his home near Dallas Center, before it was relocated again to the county museum. Scores of his architectural sketches wallpaper the room.

The museum’s curator, Pete Malmberg, remembers when Wagner used to stop by. “Here was this guy who looked like Christopher Lloyd in ‘Back to the Future,’ wearing Hawaiian shirts and speaking really, really fast,” he said.

Malmberg said the museum’s collection shows how prolific Wagner was and how varied his interests were, especially when it came to other people.

“He just loved people, from street people all the way up to presidents,” Malmberg said. “He knew everybody.”