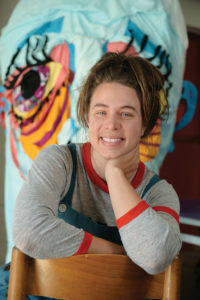

Artist Rachel Buse smiles in front of a large, less happy-looking fabric bust, a work she named “Sad.”

Writer: Larry Erickson

As a sculptor who works in fabrics, Rachel Buse thinks big. Big in concept. Big in scale. It all flows from a big imagination—and a sewing machine.

Her creations are fanciful, colorful, “like I caught exotic creatures and put them in the zoo, out of their natural habitat,” she muses.

Romance lured Buse from Lincoln, Nebraska, eight years ago and led her to Des Moines, where the relationship with musician Jared Vaughan continues happily with less exotic creatures: their cat, Out to Lunch, and dog, Juan Carlos. Vaughan performs in the bands Goldblooms and the Vehnevants.

The 31-year-old Buse (pronounced BOOzie) heads out each morning to a third-floor studio in the Fitch Building downtown, a space layered in fabrics and forms, some finished and others in various states of creative assembly.

A large figure named “Sit” occupies a chair, appropriately.

But Sit’s head is undergoing surgery on the other side of the studio. Another fabric head, fully 6 feet high, hangs slack-jawed in the basement. That sounds ghoulish, but the heads are bright, amusing and in no apparent discomfort. “A lot of reconstructive surgery goes on here,” Buse says

with the eager smile of someone who clearly loves her work.

“I work best very intuitively,” she says. “I grab some fabric, make a shape and see where it goes. Sometimes it’s

just an exploration, making some parts. Later they’ll combine with each other.” That explains the severed fabric limbs and noggins, as well as feet of colors that don’t match their legs.

The pieces have personalities and quirks that clearly delight Buse. Most get described in masculine terms as she looks around the studio: “For a show in Ames, the blue guy went, and the purple guy in the hallway. Sit came, too.”

At shows and frequently at temporary art installations, people are noticing. Des Moines artist Ian Miller had an East Village gallery when Buse was new to Des Moines and gave her a solo show.

“I found Rachel through the gallery, in the thickets of the creative scene,” Miller recalls. “She has a unique style and sensibility, and a curious nature in general. She deserved to be seen.”

‘Visceral Presence’

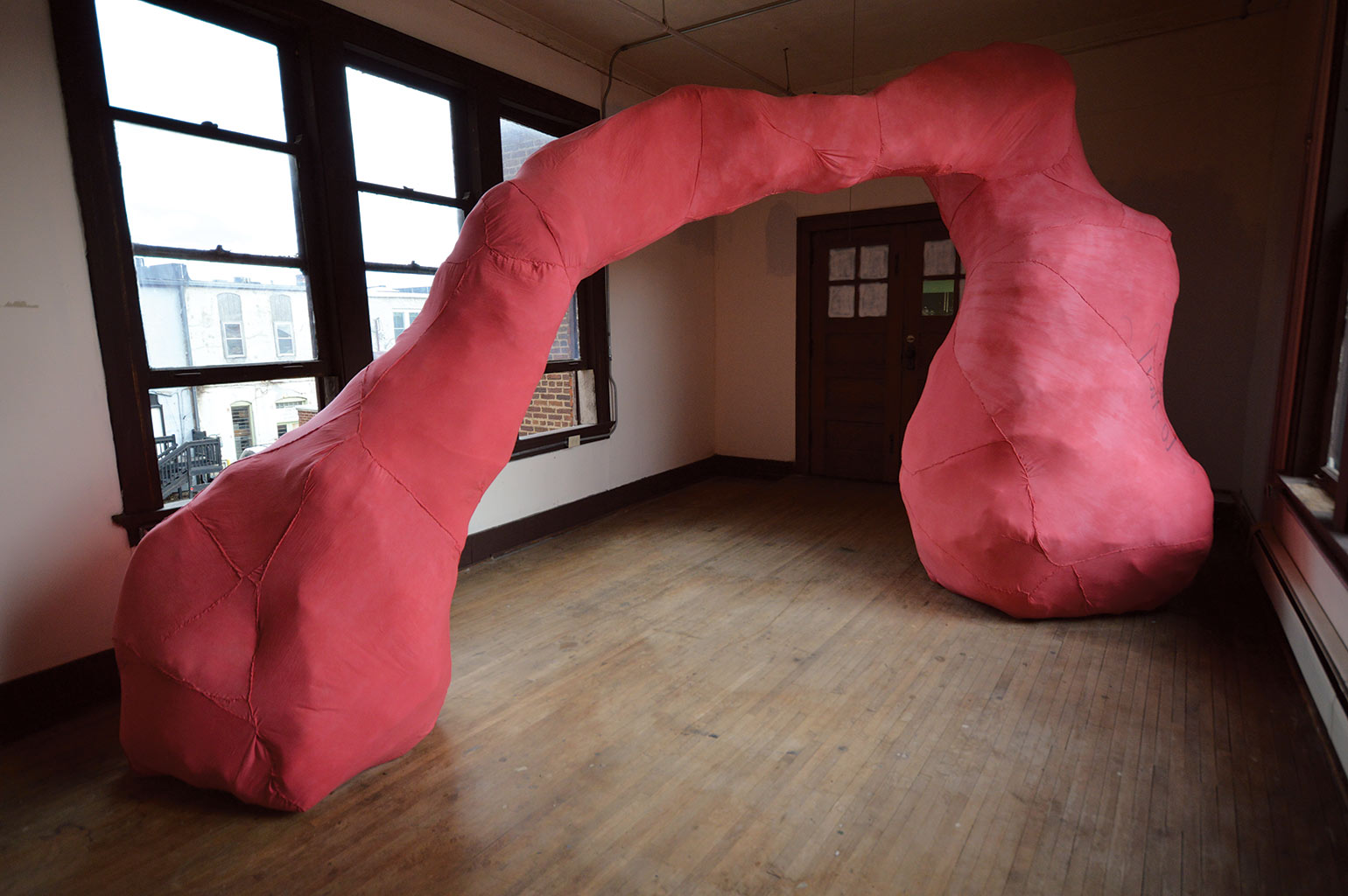

Mat Greiner went one step further, actually living with a sculptural installation that Buse created in his bedroom. Greiner manages the art collective Chicken Tractor, and his apartment becomes a public gallery several times a year.

“It’s one thing to have a painting on the wall,” Greiner says. “But Rachel’s work can become much more of a presence that is felt. She would come in and work on it, often when I was not at home. Coming home each day to this mass that had shifted form and position was very exciting, almost like a new person in my life. It was a visceral, experiential presence.”

And then it went away. Much of Buse’s works have been temporary installations, often created on-site, some in homes but more in commercial buildings and public spaces, such as the Clive Public Library last fall. An Iowa Arts Council grant helps with expenses. Moberg Gallery has helped line up sites and arranged a pop-up show.

Buse says Greiner’s assessment that her art is an “experiential presence” is exactly right. “It’s an invasion of personal space, having something so big in your home or business, but that’s the point,” she says. “It forces you to encounter art, to interact with it, to experience it more intimately than something on a wall or in a big gallery space.”

The creative process is intimate as well. “My grandmother recently gave me tons of textiles,” Buse says, “and they all kinda smell like her.”

She knows, because she works deeply in the materials of her projects, hunkered over the work, experiencing them stitch by stitch. Music soars from a radio on a window ledge, in the bright sunlight of her studio’s southern exposure.

“She works in an almost painterly fashion,” Greiner observes, “working up close, then stepping back to review the effect, then moving back into the artwork.”

Working with fabric, Buse says, “is very healing, really forgiving.” She often sees the fabric as skin, she admits, and reworking pieces as reconstructive surgery. “If I give the work the time, everything else will become clear,” she says, “where it needs to go and where it can go.”

It’s also very absorbing. “I lose all track of time, and at the end of the day, there are parts—something to respond to the next day.”

Material Matters

Buse came to fabric gradually, after exploring other materials while earning an art degree at the University of Nebraska. She had gone to an arts-focused high school in Lincoln and was always intrigued by sculpture, but not in all forms. She cringes as she recalls a welding course: “I was terrified! And I worked freakin’ hard.”

Even then, she was drawn to working in large scale. Welding 6-foot sculptures in metal? “It’s very physical.” Then came lessons on working in plaster, wood and paper.

Paper is similar to fabric in one important regard, she says: “You can go big with very light weight.”

She recalls her early efforts in fabrics, and traces their shapes with her hands, as if embracing the work as she remembers it. “To work large, textiles are great,” Buse says. “You can move it, tear it apart. You can kind of draw with it in the space, and allow it to grow.”

Buse had found her medium, but sculpture was not yet a career. She worked as a nanny for six years before her move to Iowa, then became a docent at the Des Moines Art Center, eventually teaching classes—“a lot of kids’ classes. I sculpted a giant puppy that kids painted. It went to the Des Moines Arts Festival, where thousands of kids embraced and squished it.” When your audience is kids, artwork getting “squished” is a measure of success.

“I met a lot of people through the Art Center,” she says, “and some projects came from those connections.”

She also volunteered in the early days of the Des Moines Social Club and exhibited some installations there. Then there was a 2015 gig with an arts summer camp and a residency program at the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh. “I learned from seeing how kids and their parents responded to art,” she says. “I made great connections living and working with other creative people.

I can’t wait to find another opportunity like that.”

She also has secured her place in the local community of artists. “They’re great,” she says. “Not competitive but very collaborative. … It makes everything stronger and better.”

‘More to Chew On’

As she contemplates her career, Buse has been researching the lives and development of other artists. She finds inspiration in the work of Lee Bontecou, now in her 80s, who pioneered work blending fabric sculpture and painting.

“She doesn’t try to hide how her things are made,” Buse says. “All the seams are exposed, and I try to embrace that myself. It’s seeing how something is made, the artistry of it, and not so concerned about this glossy finish. It’s just kind of yummier to me, with more to chew on.”

Thinking ahead, Buse imagines developing new skills, with different materials. “I think a lot about plastic,” she says, “and concrete.”

She wants to continue working at a large scale and with temporary installations: “If I can pop in your living room for a month, there’s something kind of exciting about that, to be a part of this strange world for a bit, and then it goes away.”

She smiles at how appealing she finds the thought of temporary, experimental work. Her phone is filled with images of installations that have disappeared. That’s just part of her process, part of her style.

“It’s unbelievable to me that I am doing this now,” she says, looking around her studio. “I have this space and I’m the boss and I’m here. In five years I’d like to have that be sustainable and strong, while continuing to develop my work.”