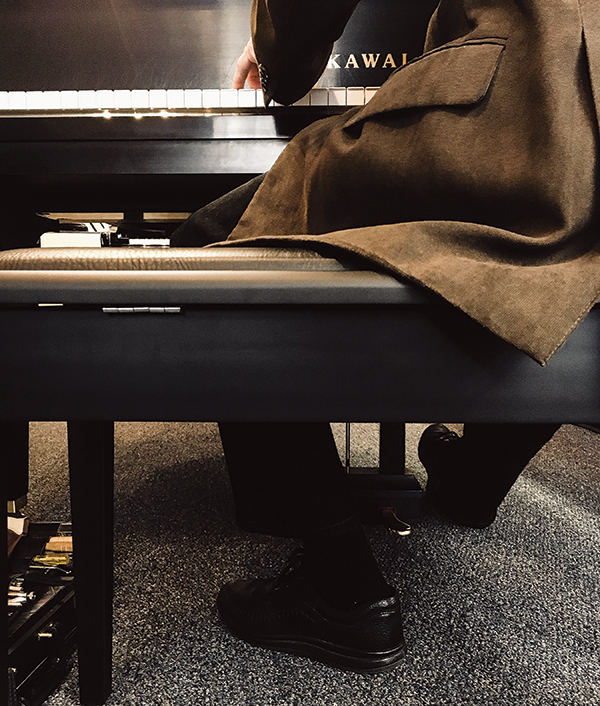

Above: It takes Lorlin Barber around two hours to tune a piano. He says his work is more mathematical than musical. “You learn wavelengths, and you hear beats,” he says. “Listening to those beats and eliminating beats in some situations is what tunes the piano.”

Photographer: Jami Milne

Writer: Jane Schorer Meisner

David Liljedahl

‘Eating Up the Keyboard’

David Liljedahl owes the discovery of his musical talent to Mickey Mouse. “I was at my aunt’s house, and the ‘Mickey Mouse Club’ came on,” recalls Liljedahl, 68, who grew up in Chicago. “I listened and then went to her piano and picked out the entire melody of the theme. My aunt told my mom, ‘This kid should be taking piano lessons.’ ”

Liljedahl was 7 or 8 when he began studying piano. He loved to play—and hated to practice. “I was a brat,” he says. Eventually, his mom hired a teacher who agreed to teach Liljedahl on a probationary basis and started him over in lessons for beginners.

“It was a rude awakening,” Liljedahl says. “He was testing my tenacity and willingness. But he also explained why we were doing things. By the time I was halfway through high school, I was practicing up to five hours a day. I was eating up the keyboard, and I was getting recognition and winning competitions.”

One competition Liljedahl entered while majoring in music at Augustana College in Rock Island, Ill., led to an offer of an apprenticeship with a piano tuner who had fled Germany in the 1940s. At the time, Liljedahl had no idea how the inside of a piano worked.

“I was thinking I could either spend my summer with my parents, or I could hang out with this really neat guy with a lot of history and learn something,” Liljedahl says.

“It was a no-brainer.”

Through that apprenticeship, he learned piano technology—and how to tune the way an old-fashioned master did.

“Anything invented after, say, 1950, he was suspect of,” Liljedahl says. “I was trained to tune by ear, with the tuning fork. Many of the things in my tech kit now he would not approve of.”

After college, Liljedahl taught instrumental music for 15 years in Laurens and Indianola schools and became an adjunct professor teaching percussion and saxophone at Simpson College. Then he returned to Chicago and worked on his master’s degree at VanderCook College of Music, where he was required to play every musical instrument at an upper high school level. To support himself, he played professionally for theater productions—and made use of his training in, as he says, “piano servicing.”

Knowledge of music can benefit a piano tuner, but it’s not required, Liljedahl says: “When I’m listening to two notes, I’m not listening to either one. I’m listening to the relationship and listening for beats.”

In 1994, Liljedahl moved to Urbandale and became head piano technician at Rieman Music, partly to service Steinway pianos, which require some specialized skills. He almost always arrives on the job in a jacket and tie—just as his German mentor insisted when he was an apprentice. His assignments have led to acquaintances with such famous musicians as Roger Williams, Peter Nero, Emanuel Ax and Victor Borge. Liljedahl is one of only five piano tuners within 100 miles of Greater Des Moines who have earned the elite registered piano technician designation, which requires passing a set of rigorous exams.

Liljedahl, who can sometimes wax philosophical, sees servicing a piano as seeking a more perfect way of expression. “It furthers communication of the arts,” he says. “If a piano key doesn’t work, then something is not right. It’s like somebody took a letter away from your vocabulary. The message doesn’t get across. So that’s what I do. I promote getting a message across.”

Lorlin Barber

A Musical Life

Lorlin Barber grew up in Polk County, Neb., the son of a small-town Pontiac dealer. One day, his father announced that the then-6-year-old boy was going to take piano lessons.

“The lessons were part of a trade on a ’56 Star Chief four-door hardtop, red and white,” Barber says. “I was a part of trades on many transactions for cars. Most of the fillings in my mouth are a trade for a ’62 Bonneville.”

Regardless, the piano lessons agreed with the youngster, who also was heavily influenced by his music-loving mother, who worked for Lockheed in San Diego during World War II and had the opportunity to meet many popular musicians of the time. “She knew the Ink Spots and was introduced to Duke Ellington. She knew Count Basie,” Barber recalls. “She had a lot of records that most people didn’t have—jazz 78s. I listened to a lot from her library.”

Later, as a music major at the University of Nebraska in Kearney, the now-66-year-old Barber earned most of his tuition money by playing bass at gigs. But he had no idea where he was going with his music.

“I played around town a lot, I was in opera and I played dates for the theater department,” he says. “But I hated the idea of teaching.”

So he worked as a booking agent in Minneapolis for 12 years, then managed properties in Los Angeles that included studios used by musicians for rehearsals. He played clubs in Boston and taught piano tuning in Cuba.

Barber was rebuilding and refurbishing Steinway pianos in Hancher Auditorium at the University of Iowa when he was persuaded to move to the Des Moines area in 1989. Now the Polk City resident owns his own business, Barber’s Piano Service in Clive, and tunes pianos in private homes and public venues.

“I’ve done Wells Fargo, the Civic Center and Sheslow Auditorium,” says Barber, who’s earned the prestigious registered piano technician designation from the national Piano Technicians Guild. “But the concert work I do is

mostly at Hoyt Sherman Auditorium. I know all the artists at Hoyt Sherman.”

Preparing for a concert is often a daylong job, he says: “You tune the piano in the morning, then they have sound checks and they might have a rehearsal, or they might not. Then about an hour or hour-and-a-half before they open up the doors, you retune the piano. I’ve always enjoyed it, because I get to meet some of the coolest people. I used to sit down and talk with [the late piano great] Roger Williams for an hour before we’d do anything. He had great stories.”

Barber did one especially memorable assignment in downtown Des Moines in July 1993. It was the weekend that the Des Moines Grand Prix was washed out by raging floodwaters. “I was down there tuning a piano on a stage while they were having time trials during the day,” Barber says. “That night, the piano floated down the river.”

With approximately 3,800 customer names in his files, Barber says he’ll keep working until he can’t do it anymore. It is strenuous work, after all.

“Turning a steel cylinder-like tuning pin involves around 166 pounds of tension, and you’re doing that up to 250 times per piano,” Barber says. “I go to the Y four times a week just to keep my strength up.”

Registered piano technician David Liljedahl tightens piano strings by turning tuning pins with a tuning hammer, which is actually a wrench. “I’m intensely focused when I’m cranking my tuning pins,” Liljedahl says, “because I’m listening for different things.” Pianos have an average of between 230 and 250 strings, resulting in more than 25,000 pounds of tension going laterally.

Being a successful piano tuner requires an understanding of mathematics, geometry, physics and acoustics, says David Liljedahl (pictured above at the piano). “You have to like working with your hands and understand tools and how they work.”

Liljedahl says he could be busy six days a week, but he’s gradually cutting back on his workload. “The demand is so great that I started one apprentice, and now he’s got as much work as he wants,” he says. “Another person apprenticed with me several years ago, and now he’s full time.”

Tuning a piano means setting the relationship between the strings. “There is a standard, international pitch, which is A4,” David Liljedahl says. “It should be at 440 vibrations per second.”

Registered piano technician Lorlin Barber (pictured above at Noce) recommends tuning pianos every six months, once in the winter when the air is dry and again in more humid weather.

“When the soundboard takes on moisture, it rises like a loaf of bread so the strings get tighter and sharper,” he says. “The opposite happens in winter when you turn the heat on.”

The soundboard is what puts a piano out of tune. “That’s your amplifier,” Barber says. “It’s like a Roman arch, which is one of the strongest architectural designs.”

Servicing a piano can be a strain on a technician’s lower back as he adjusts the enormous amount of tension in the strings. “Your posture at work is important, and you have to be quick, accurate and stable,” Barber says. “You have to know what you’re doing.”