In “Bridge Study #2,” Olivia Valentine interprets the structure of a downtown Chicago bridge by overlaying the photograph with handwoven bobbin lace. Other materials in the work are ink, paper and pins on board.

Writer: Vicki L. Ingham

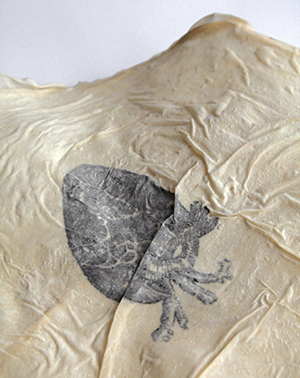

Firat Erdim, a phyllo dough maker and a tattoo artist in Turkey collaborated to create “Yufka Yurek,” a 22-inch square of phyllo dough tattooed with a heart.

You’d be hard-pressed to suggest something that Olivia Valentine and Firat Erdim couldn’t make into art. Some thread? She’s done it. Rocks? That’s his. Tattooed phyllo dough? Yes. In fact, that creation ended up as part of an exhibit in Illinois, shipped from where the artists were living in Turkey at the time.

“They have an interesting conceptual component to their work,” says Des Moines artist Christopher Chiavetta, who has a studio across the hall from Valentine in the Fitch Building. “They’re dealing with different perspectives of looking at the world. I find that interesting, because it makes me look at where I am, where I am existing, in a different way.”

Connecticut native Valentine and Turkish-born Erdim, both 38, met in 1996 at New York’s Cooper Union, where they studied architecture. Valentine left after two years to pursue a BFA in photography at the Rhode Island School of Design and began using crochet to create large-scale textile constructions. She later earned an MFA in studio art from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Erdim received his bachelor’s degree in architecture from Cooper Union and his master’s from the University of Virginia. In addition to teaching architecture, his artistic practice has included drawing, installation, performance and sculpture.

Erdim’s “Hisar Study” series puts a creative spin on gabion construction (wire cages filled with rocks or concrete), more typically used for erosion control on steep slopes or in gullies.

After they married in 2003, teaching positions, fellowships and grants often sent them to different states and even different countries—one of the challenges for academic couples is finding suitable jobs in the same place. Now, however, they have a chance to put down some roots. In 2016, they accepted tenure-track positions in the College of Design at Iowa State University, and they’ve bought a house in Des Moines’ Sherman Hill neighborhood—a strategic choice, Erdim says.

“There’s a larger community [in Des Moines] of people involved in various art and design practices,” he explains, “and we didn’t want to limit ourselves to the university community as newcomers. Everybody’s been really friendly, really open, really nice.”

Exchange of Ideas

Although they pursue different interests, the two share a fundamental outlook that encourages a constant exchange of ideas and techniques, communicating often, “even if we’re not in the same country,” Valentine says. “Drawings of Firat’s are string constructions with pins, and a lot of my work is string constructions with pins.” His drawings refer to structures, as do her textiles. “There’s a continual intellectual and visual dialogue,” she adds.

The communion of minds doesn’t extend to shared studio space, however. While Valentine’s studio is housed in the Fitch Building, Erdim has set up shop a few blocks away, in Elevencherry at 11th and Cherry streets. “As much as we can get along,” Valentine says, “our acoustic sensibilities are sometimes different.”

In Valentine’s “Punto in Aria (Pilaster),” an installation in Chicago, Mylar balloons top a tatted column anchored to the floor with pins.

Messiness is another distinction between their ideal work environments. “Most of what I do involves some kind of dirt or mess or spray,” Erdim says. “Olivia’s work requires a much cleaner environment.”

That work includes the painstaking technique of making bobbin lace, which Valentine taught herself in 2008. Valentine’s father was a city engineer, and as she was growing up, she loved drafting and drawing plans with him. When she began to crochet large-scale textiles, she saw the patterns “as architectural drawings, church apses, Gothic city plans within these textile structures that I was making.”

She learned that bobbin lace is made by twisting and crossing sets of threads and pinning them to a paper pattern, and the discovery was a revelation: “It’s a very direct way of taking a drawing and

translating it into a textile structure that is then a physical object, and those relationships became instantly apparent and very exciting to me.”

In addition to weaving large-scale lace constructions, Valentine has followed the idea of lace as a fabric edging into more abstract meditations on edges. One result was a series of photographs she created in 2013 while in Turkey on a Fulbright fellowship. With a camera on a tripod set for multiple exposures, she photographed herself walking along the edges of mountains and fields in Cappadoccia.

“I didn’t go to Turkey with the idea of walking along the edge of a mountain to create photographs,” she says. “I went thinking I was going to learn the relationships between a specific type of textile I was studying, oya, and landscape and architecture in Cappadoccia.”

That curiosity led to a series of walks that Valentine describes as “a bodily performance” involving a head scarf edged with oya, a Turkish lacework: “To me, that edge along the mountain became synonymous with the edge of the head scarf, which is a border between a private and public space, an interior and an exterior display.”

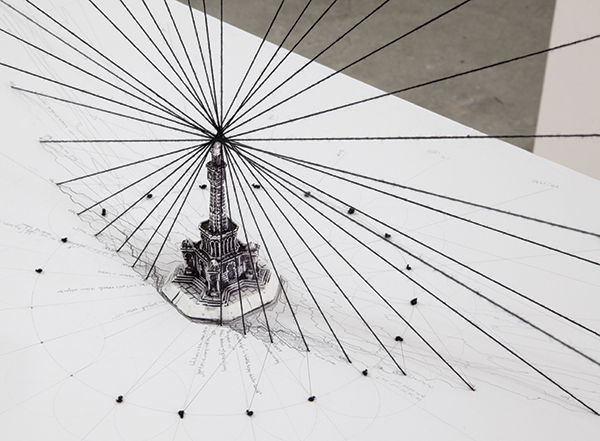

A miniature souvenir model of the Konak Clock Tower in Izmir, Turkey, anchors this reconstruction of Erdim’s performance in the plaza itself in 2013. Playing on the idea of time-keeping, he used the actual clock tower as a sundial and recorded the shifting shadows in a drawing, along with conversations with journalists, undercover police and passers-by.

Materials and Context

The wide-ranging scope of Erdim’s artistry results partly from where he happens to be and partly from what materials present themselves. “Say there’s a whole pile of good rocks,” he says, and he’s in Chicago or Turkey. The materials and context ignite a conceptual process that leads to a physical expression—in the case of the rocks, “Hisar Constructions,” a series of columns of stones or rubble encased in crocheted “cages” of various shapes and placed in landscape and gallery settings.

“I don’t think of a product and make it,” Erdim says. “That’s not usually how I’m thinking about things. There’s always a kind of back and forth, the product is feeding back into the process. Most of the time in my work it’s rare that something is just once. Usually it’s a series of things.”

As an example, during the couple’s stay in Turkey in 2012 and 2013, the Gezi Park protests erupted. (Erdim was a visiting faculty member at Izmir University of Economics at that time.) “That affected both of us pretty strongly,” Erdim says. A heightened awareness of what is allowed or forbidden in a public space stayed with him when a teaching position took him to Segovia, Spain, in 2013.

There, the streets and plazas were always crowded with people walking, talking or participating in political, religious or holiday processions. “There was constantly a kind of occupation of the street through these processions,” he says. “I felt very much like an outsider watching these things happen, and I wanted to participate but I’m not Catholic, I’m not Spanish.”

So in 2014 he decided to walk the streets in his own kind of procession, using the church bell towers that punctuate the city as his navigational guide. He took photos every few minutes to mark his progress and then used the photos to create large pencil drawings (up to 130 inches wide) that suggest the experience of the city’s topography.

He continued the project in Rome (2015), and this past summer extended it to the Camino de Santiago, a network of early Christian pilgrimage routes in Spain.

Creative Collaboration

In addition to their individual pursuits, Valentine and Erdim have engaged in creative collaborations on projects ranging from the ephemeral to the ecological. When a tattoo artist and a phyllo dough maker moved into the Turkish covered market where Erdim and Valentine had rented studio space in 2012-2013, Erdim thought it would be interesting—and kind of a joke—if he could put the two of them together. They ended up shipping the tattooed phyllo dough (along with their own pieces) to a 2013 exhibition titled “Fleeting,” at the Indi Go Gallery in Champaign, Illinois.

On a larger and more complicated scale, the pair collaborated with several landscape architects to promote the eventual re-greening of an area on the edges of Rome. The project unfolded in 2015 while Erdim and Valentine were at the American Academy in Rome. It involved cooperating with two groups: an immigrant community illegally occupying a vast former salami factory and the Museo dell’ Altro e dell’ Altrove di Metropoliz (Museum of the Other and the Elsewhere), which invites artists to create work in and on the factory structure.

For the collaboration, patterns were incised into the concrete outdoors and planted with indigenous seeds, with the idea that they would initiate a process of ecological succession. Valentine developed the patterns from her study of mosaic floors in Rome.

Getting Involved

Although developing new courses absorbed them during their first year at ISU, both Erdim and Valentine look forward to becoming involved in the Des Moines art community. “There are a lot of strong local site-specific projects here already,” Valentine says, “and we want to see how we and our practices fit into that. I was excited to come back to the Midwest; it’s a great place to make things.”

She already has joined forces with Des Moines artist Rob Stephens on a proposal for a public art project downtown. Although the status of the proposal is still up in the air, Stephens says the collaboration “just naturally seemed to happen. She’s super enthusiastic and very encouraging.”

Erdim and Valentine “are definitely bringing a high level of work to Des Moines,” Chiavetta says. “I think their work raises the bar a bit. It’s good for other artists to be exposed to, and in general it makes the city a more interesting place.”