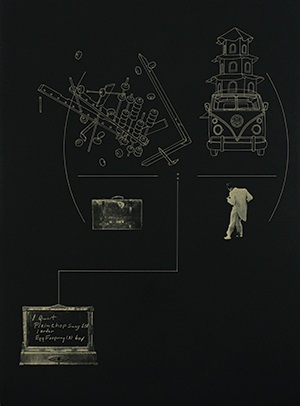

Above: In creating the relief etching “My Father and Dillinger,” artist Phillip Chen drew on a family story revolving around Chen’s dad, who worked at a Chicago restaurant in the 1930s and often served the infamous gangster.

Writer: Michael Morain

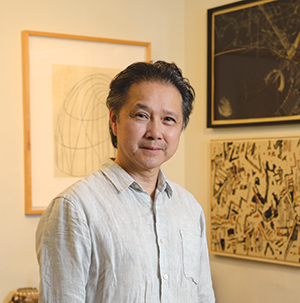

A few years ago, a National Institutes of Health biologist asked Des Moines artist Phillip Chen to create a piece of artwork for the sprawling NIH headquarters near Washington, D.C. The result is a print called “Data and Theory” (right), an image of a strange ceramic jar on an inky black background, which the biologist saw every day at work, pondered often, and liked so much that he discussed it with Bill Gates during a laboratory tour.

The biologist, Peter Kwong, now works at Columbia University but recently persuaded NIH to commission Chen to create another print to celebrate the ongoing development of an HIV vaccine. After 37 years of research and 35 million AIDS deaths worldwide, scientists are on the verge of finding a practical cure.

“This is such an important achievement,” says Chen, who’s been studying progress reports for artistic inspiration. “I’m a little worried, but that’s good. It’s the most difficult project I’ve ever undertaken.”

If anyone is up to the task, it’s Chen. He won a Guggenheim Fellowship this spring, and his elegantly precise artwork hangs in museums and private collections across the country. Like an NIH scientist—or perhaps a forensic detective—he has a knack for spinning new theories from old data, for extracting fresh insights from stale facts. Many of his compositions look as if he unsealed a bunch of evidence from a cold case and then rearranged it, as if to say, “Hey, look—what about this

?”

Chen, 64, grew up on the north side of Chicago and earned degrees from both the University of Illinois and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He taught for several years at both of his alma maters, plus Northwestern University, before joining the Drake University faculty in 1995. Throughout his academic career, he’s always gotten his hands dirty in the studio.

“Not only is he an exquisite technician, but his work has a warmth and a depth and an intellectual curiosity,” says Jeff Fleming, director of the Des Moines Art Center. “He combines marvelous, bizarre found objects in interesting ways.”

Comfortable At Home

Many of those objects clutter the 99-year-old South-of-Grand home Chen shares with his wife, Lenore Metrick-Chen, on a leafy corner of Greenwood Drive. Both work at Drake—he teaches drawing and printmaking, she teaches art history—and their house has filled over the past 20-some years with the slow tide of their confluent interests: ceramics, African folk art, a print by their friend Martin Puryear (whose work also graces the Pappajohn Sculpture Park), a lazy cat named Cosmo, and keepsakes from their two grown daughters, Cora and Shaye. When asked to fetch the Guggenheim Foundation’s official embossed letter, Chen wasn’t quite sure where to look until he plucked it from a stack of papers upstairs.

In this setting, it’s easy to imagine how the artist might spot a connection between a coffee cup and the curve of an African mask or the hand-me-down history of an antique chair. Most of his artwork features odds and ends floating like ghosts through space.

“There are these wonderful, mysterious narratives,” Fleming says.

Chen makes most of his artwork at Drake, in a well-worn studio just west of the stadium. He photographs objects and then prints the photos onto transparencies, which he often overlaps with tracing-paper drawings before sliding the whole collage into a jumbo photocopier that exposes a metal printing plate to light. From there, the plate goes through a chemical bath, a rinse, a rub of ink and, at last, the heavy hand-cranked press that rolls out the final product.

He teaches the step-by-step process to his students and, in doing so, brings “a great sense of creative energy and urgency to the Drake community,” Drake President Marty Martin wrote in an email. “While it’s wonderful to see his talents recognized by an organization as prestigious as the Guggenheim Foundation, it is Drake students who are the primary beneficiary of his talents through his teaching and mentorship.”

Guggenheim Fellowship

As it turns out, Chen is the second Drake professor to win the Guggenheim (after film scholar Richard Abel, in 1993). He is the third Iowa visual artist to win (after University of Iowa professors Byron Burford, in 1960, and Sue Hettmansperger, in 2008), and the 28th Iowan across all disciplines since the foundation handed out its first fellowships in 1925.

Chen flew to New York this spring for a swanky reception with this year’s 172 other new fellows, who were selected from almost 3,000 applicants nationwide. They were joined at the event by fellows from 2008, 1998, 1988 and so on, like a class reunion.

Hettmansperger bought her plane ticket but broke her leg right before the trip. “It just killed me,” she says.

Looking back over the last decade, she appreciates the fellowship’s financial boost—it varies from one person to the next and usually remains confidential—but also the way the fellowship helped her to take more artistic risks and attract more commissions. Coincidentally, she and Chen were both tapped to create artwork for the University of Iowa’s Pappajohn Biomedical Discovery Building in 2016.

She still wonders who was on the secret Guggenheim jury and exactly why they chose her.

“I think I won because I’m concerned with the environment and the future of the planet,” she says. “Art can push a society toward resolutions to various problems, and I think that’s what they’re looking for. If anyone asked my advice about how to apply, I’d tell them to connect their work to some grand theme, to something larger in the world.”

Honoring Family History

Chen certainly does. Some of his artwork brushes his own family stories into the broader sweep of American history.

A print called “Kuo Chung’s Release” (page 82) was inspired by Chen’s great-grandfather, who joined the California Gold Rush and almost drowned when he dived into a river to catch fish and got his ponytail caught between two rocks. His friends cut him free, but he couldn’t return to China until his hair grew long enough to braid into another tail, called a queue, which the Qing Dynasty required until the early 1910s. Men who broke the law faced execution.

Another print, called “My Father and Dillinger” (pages 78-79), was inspired by Chen’s dad, who worked at a Chinese restaurant in Chicago in the 1930s and often served the infamous gangster. Similarly, “Presque Vu” (page 83) honors Chen’s uncle, who ran the only racially integrated restaurant

in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and served legendary jazz musician Cab Calloway whenever he passed through on tour.

Lately, Chen has been looking more broadly at America’s black and Asian—“blasian”—culture. He plans to use part of his fellowship money to visit Louisiana, where Chinese workers were brought in during the late 1860s to compete with former slaves. But instead of competing, the two groups often worked together, intermarried and even developed their own mash-up language.

Printmaking and Social Justice

Chen’s artwork focuses on “printmaking’s ability to proliferate critical pronouncements on behalf of social justice,” according to his Guggenheim application. He writes that his most recent works “address the hateful words and retrograde actions of some of our elected officials,” including “Iowa’s fascist-leaning Representative Steve King, who stated earlier this year, ‘We can’t restore our civilization with someone else’s babies.’ ”

That may seem like a much different subject than the ones Chen explores at the National Institutes of Health, but his intellectual process is the same. To make the print of the ceramic jar at NIH, he made a clay vessel, smashed it, and then used only a few of the broken pieces, forcing him (and the print’s viewers) to imagine, as archaeologists do, how the rest of the vessel might have looked.

It’s all about assembling the bigger picture, the more perfect union, which requires a little curiosity and a lot of persistence, of which Chen has plenty.

Keep in mind: He first applied for the Guggenheim 15 years ago. It took him four tries.

“He’s intrepid,” says Warren Obluck, a local collector who owns one of the “My Father and Dillinger” prints. “Once he sets a goal he really works to achieve it. This won’t be the last thing he achieves, by any means.”