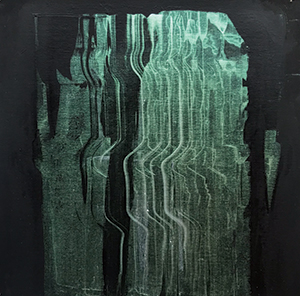

Above: Intricacies of color and pattern emerge in this detail of a painting that Christopher Chiavetta was working on when we visited.

Writer: Kelly Roberson

Photographer: Karla Conrad

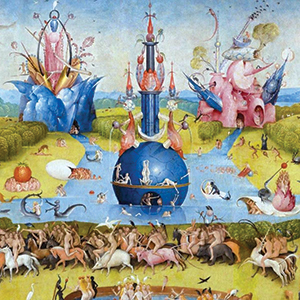

Peer long enough at the triptych “The Garden of Earthly Delights” (see image detail, below), and the prismatic vision of the 15th-century Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch becomes apparent. Here, in his masterpiece, are the ponderings of someone interested in what’s beyond the physical world, a meditation on the afterlife and fantastical forms and beings.

Spend time with the work of Des Moines artist Christopher Chiavetta (pronounced key-ah-VETT-a)

and you’ll notice the similarities between his imagination and Bosch’s pursuit of the unknown. “Bosch and [English landscape painter] John Martin are the two that loom the largest in my imagination,” says the 45-year-old artist. “They have had the most influence, as evidenced by my interest in dramatic and often cataclysmic landscapes.”

Chiavetta’s approach to art traces back to his childhood in Rochester, New York, in the 1980s. Shaped by his Roman Catholic upbringing as well as the Cold War—they “instilled in me at an early age a preoccupation with end-of-the-world scenarios and apocalyptic imagery,” he says—Chiavetta absorbed it all.

“My parents were not artists, and they say I didn’t enjoy speaking very much—I probably didn’t speak until I was 4,” he says. “But I was able to express myself through visual media, and that has remained true my entire life.”

Post-high school and faced with a decision, Chiavetta flirted briefly with the idea of becoming a monk—“it was freedom and isolation,” he says. Instead he decamped to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (now a part of Tufts University). “I have a tendency to work at my own pace, which works for me and against me. I spent a lot of that time staring at my work,” Chiavetta says with a grin.

His time in school cemented a lifelong approach to work that’s as much internal as it is external. “I still go through periods of producing lots of work and then spending a lot of time thinking,” he says.

Making Art Work

Chiavetta left art school after two years and eventually made his way to Georgia State University, fortuitous for several reasons. He would graduate in 2004 with a film studies degree and a minor in Japanese, even as he continued painting, and he would meet his wife, Leah Kalmanson. The two married and moved to Honolulu so she could pursue a Ph.D. in philosophy; the couple also detoured to Japan for a year of her studies. Chiavetta continued to create art and showed and sold his works here and there.

“I remember working on one particular piece in our house, and I had spent a really long time on it,” he says.

“I was working more or less part time and painting more than I was working. I realized that I needed to figure out a way to make this work.”

In 2010, the couple moved to Des Moines; Kalmanson is now an associate professor of philosophy at Drake University. After landing here, Chiavetta pursued art full time, eventually moving from a studio in his home to a spacious one in the Fitch Building.

Those in the Des Moines art community were impressed with what they saw. Susan Watts, owner of Olson-Larsen Galleries, saw Chiavetta’s work in a show in 2014 and was, she says, “blown away. Christopher is a painter’s painter. He is serious and careful with his craft. I consider his work to be very formal. Some abstract artists work very quickly, and the work is more reactive. Christopher is in a different camp—he takes his time with his work. There are many layers, both of material and of concept.”

Contemplative Practice

Rumination still guides Chiavetta and reflects the core of who he is and what he creates. “Art is largely a contemplative practice for me, and I flesh out ideas that come as they may,” he says. “I consider myself a landscape painter, but the landscape I return to over and over is a broad spectrum of things that are seen and unseen: reality, creation, the formless void, unbounded space. Those ideas have always been with me.”

That metaphysical preoccupation connects to the work of Bosch and similar painters. “If I’m going to consider the landscape more than what we see, and consider that something like a mountain [is] more than just this object that we would label, I have to approach it from all angles,” he says. “I make paintings that I think of as portals to other places. I always wanted to make paintings where you are immediately face to face with something, to express something that overtakes us.”

His paintings “are both abstract and very organic to me,” says Jennifer McCrickerd, who’s commissioned a painting from Chiavetta. “He has called them surreal landscapes, and that does a really nice job of capturing what they are. I’ve told Christopher that I’d like to just be able to climb inside of his paintings and experience being immersed in them. His works evoke, for me, a sense of peace and beauty while also keeping me engaged.”

This fall, Chiavetta started working on his MFA at Iowa State University. “I’m pretty solitary most of the time and felt I was lacking the opportunity to learn other things,” he says. “And I started thinking that no one is holding me accountable. I have so many ideas and threads I would like to tie together in a greater project, and school seemed like the logical place to do it.”

The thread that Chiavetta pulled all those years ago in Rochester—that the visual world was the best way he knew to make sense of his time on earth—continues to guide him: “I don’t really feel like I need to chase ideas of success. For me, I have a huge, beautiful studio, I’m making the exact paintings I have been trying to make, I have a gallery that represents me that is incredible, and there are people here who are really excited about the art happening in Des Moines.”

A detail from “The Garden of Earthly Delights” (circa 1500), a triptych oil painting on oak panels by influential Dutch artist Hieronymus Bosch.

Chiavetta’s acrylic on canvas painting “Dragon Red,” 62 x 60 inches.

“Ground of Unknowing,” oil and acrylic on canvas, 62 x 60 inches.

“Green Wind,” acrylic on paper, 12 x 12 inches.

Detail of linear exploration from a work in process.

The large oil on canvas painting “Mineralization,” 60 x 120 inches, is priced at $8,000 at Olson-Larsen Galleries.