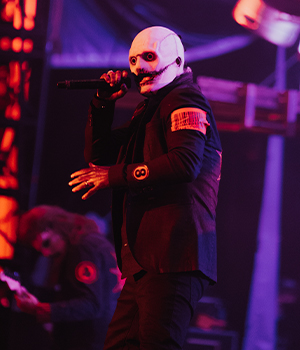

Slipknot, one of Iowa’s most influential cultural exports, was the headlining act at last year’s Knotfest in Indianola. Currently the band is on a 60-stop international tour and also expects to release a new album this year. Front row, from left: Shawn “Clown” Crahan, Jay Weinberg, Craig Jones, Sid Wilson, Alessandro Venturella. Back row, from left: Mick Thomson, Corey Taylor, Jim Root. Photographer: Anthony Scanga.

Writer: Kyle Munson

No heavy metal guitars to be heard on this remote patch of Iowa soil—only the howling winter wind. The sound is no less fierce when you consider it whistles with its own brand of pastoral dread: What wild beast may prowl over the next ridge or lurk among the shadowy timber?

Just ask the resident farmer on these 100 acres, Sid Wilson.

Wilson, 45, has locked eyes with a mountain lion that startled him from no more than 30 feet away.

He spotted the lion “crossing the gravel road with a big red hen in its mouth flapping its wings,” he said in January from the comfort and safety of his kitchen, over a cup of coffee.

The massive cat—looming larger than Wilson’s gentle giant of a 6-foot, 4-inch long, 150-pound Irish wolfhound, Seamus—leapt across the road in a single bound and disappeared with its prey.

Such is modern farming for a man whose day job as a musician in Iowa-bred metal band Slipknot sees him surrounded not by rural wildlife but the festooned, shrieking fauna of the music industry.

Last September, Wilson and his eight band mates occupied a different patch of rural Iowa with their Knotfest outdoor music festival. A throng of 30,000 fans (affectionately, “maggots”) blanketed the rolling hills of the Indianola Balloon Field. There were long lines for food and drink but also two stages full of acts such as Megadeth—a band that helped inspire Slipknot but now was supporting it.

Slipknot—a gloriously mutated hybrid of Kiss theatricality and Metallica thrash—has long since earned its place among Iowa’s most influential cultural exports, a cathartic maggot roar unleashed from the depths of flyover country. The Slipknot nine in their signature macabre masks helped usher in a more visceral 21st-century notion of corn country a few generations and Jägerbombs (and F-bombs) removed from the 76 trombones of Meredith Willson’s “The Music Man.”

“For the longest time, nobody in Iowa respected us,” says lead singer Corey Taylor. “The fans loved us, but the establishment had no time for us. … It honestly just encourages all the kids from Iowa to love us even more.”

Slipknot’s first four albums, released 1999-2008, all notched platinum sales (at least a million copies apiece). The band has been nominated for 10 Grammys, winning one. They also continue to tour; the group performed at least 28 shows in 2021, and more than 60 performances this year will wind throughout the United States, Canada, Eastern Europe, Japan, Chile, and Brazil. A new album also is due out this year.

Physical Toll

While professional headbanging may not match the rigors of the NFL, heavy metal isn’t kind to the aging bodies of a band approaching 30 years in business.

Last fall while swinging a bat against one of his percussion kegs on stage, Shawn Crahan, the 52-year-old Des Moines native known as Clown, tore a bicep so badly it required surgery.

Taylor has endured surgery on both knees, torn MCLs and ACLs, replaced vertebrae and discs, scar tissue on his eyes and scalp, burned legs, broken toes, dislocated shoulders, torn rotator cuffs, and an allergic reaction to a spider bite. Last summer he suffered a bout of COVID-19. “And people wonder why it hurts to get on stage,” deadpans Taylor, 48.

A young Wilson routinely dove 15 feet off speaker stacks into the mosh pit. An awkward stage landing in 2008 broke both his heels. Earlier this year he livestreamed on his @sidthe3rd Instagram account from an orthopedic clinic in Santa Monica, California, as a doctor injected fluid into his creaky knees.

“Everything from the hips down is pretty beat up,” says Wilson, who often shuffles off stage or through long airport terminals with help from a cane.

But the most persistent wounds for Slipknot are emotional. Tragedy has been threaded through success. In 2019, Crahan suffered the death of his 22-year-old daughter, Gabrielle, who had long struggled with drug addiction. Figuratively adrift, he and his wife spent the summer of 2020 living on a houseboat on Saylorville Lake. “We lost a child,” Crahan says. “When that happens, I no longer can pretend about anything.”

Loss of Bandmates

Within Slipknot’s ranks, band members mourned the loss of bassist Paul Gray, who died at age 38 in 2010 from an overdose of morphine and fentanyl, and drummer Joey Jordison, who died last year at 46 of undisclosed causes.

Jordison died eight years after he had left the band. He struggled with the neurological disorder transverse myelitis that took time to diagnose and temporarily robbed him of control of his legs. Wilson had remained in touch with Jordison after the split. “He did find peace, and he did find God,” Wilson says, choking back tears. “That’s probably about all I can say. But I will say that he was my friend to the end—absolutely.”

During Knotfest Iowa, there was no spoken tribute to Jordison or Gray—only a memorial banner that unfurled from high above stage at the end of Slipknot’s set.

Social Media Silence

Taylor today also prefers subtlety on social media. He swore off Twitter two and a half years ago and now delegates maintenance of his @CoreyTaylorRock handle. He occasionally forwards a message to be posted—such as in 2021 when he got dragged into a public beef with rapper Machine Gun Kelly.

“The worst thing I ever discovered is the infinite scroll,” he says.

Appropriately enough, Taylor’s lyrics for the recent dystopian Slipknot single “Chapeltown Rag” imagine social media as a conglomerate modern news source spewing lies.

Wilson by contrast, claims to remain mostly unfazed by his life online. He gets splashed across tabloid news, for instance, as the new beau of metal icon Ozzy Osbourne’s daughter, Kelly Osbourne. Wilson says he’s proud to proclaim his love for her.

At Knotfest Iowa, Wilson qualified as perhaps the creepiest band member. He stalked the stage wearing what looked like a red Jedi robe. His face was hidden behind a golden mask whose mechanical mouth mimics all of Taylor’s vocals. Wilson dreamed up the mask in 2004 but couldn’t make it a technical reality until now.

“I call him Darth Sid,” Taylor says with a chuckle. Or “Sith Wilson.”

The band loves performing now more than ever, Crahan says, “not because of COVID proving it could go away, but because we’ve always known it could go away.”

Their maggots haven’t deserted them. Slipknot’s latest album, 2019’s “We Are Not Your Kind,” sold 118,000 copies within its first week—hitting No. 1 on the charts in the United States and nine other countries. The song “Unsainted” racked up 4.7 million views within 24 hours on YouTube.

Just before Knotfest Iowa showtime, Taylor huddled with the rest of Slipknot and offered not so much a pep talk as a dose of perspective on the surreal homecoming that filled him with gratitude.

“Don’t look at this as a victory lap,” he told the band. “Because this is still a long road for us. There’s still so much that we want to accomplish. … This is just one more step on that journey.”

Guitarist Jim Root, shown here at last year’s Knotfest, is also known as No. 4. Photographer: Bryce Hall.

The 9 masked men of Slipknot: 8 Gen Xers and 1 Millenial

Only two band members—Sid Wilson and guitarist Mick Thomson—apparently still live in the Hawkeye State, among a Slipknot diaspora now spread from coast to coast. The modern lineup, in alphabetical order:

Shawn Crahan, 52, percussionist: Band co-founder Crahan, the “Clown” thanks to his series of spooky masks worthy of Stephen King, maintains a home in Johnston, site of his squash and hot pepper garden, but now lives in Palm Springs, California. The vegetarian has shed at least 80 pounds in the pandemic.

Craig Jones, 50, sampler: The most stoic stage presence of Slipknot crafts electronic samples—such as Al Pacino shouting “Here comes the pain!” from the 1993 film “Carlito’s Way”—to construct a detailed sonic tapestry behind the roar.

Jim Root, 50, guitarist: He and Corey Taylor were fellow members of Stone Sour prior to Slipknot and kept recording and touring with that hard rock band between Slipknot cycles. But Root was dismissed in 2013, and two years ago Stone Sour was put on indefinite hiatus.

Corey Taylor, 48, singer: Taylor, who also leads multiple side projects and has written four books, began living part-time in Las Vegas a dozen years ago and finally sold his West Des Moines home in 2020, spurred by the pandemic.

Mick Thomson, 48: Thomson’s hockey mask is one of the band’s most consistent visual fixtures. “It’s not really going to change too much because I haven’t changed,” he told Guitar World. “I couldn’t imagine having anything else on and being out there onstage.”

Michael “Tortilla Man” Pfaff, , 49, percussionist: The remaining obscure figure in a band that began by disguising its faces and identities, he replaced Chris Fehn, who in 2020 settled a lawsuit against his former bandmates over his earnings.

Alessandro Venturella, 43, bass: The British bassist became the permanent replacement for founding member Paul Gray, who died in 2010.

Jay Weinberg, 31, drums: The youngest member picked up the sticks in 2014. He’s no stranger to replacing landmark timekeepers, having occasionally filled his father Max’s shoes in Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band.

Sid Wilson, 45: Also known as DJ Starscream, he’s the third Sid in his English family, raised in the Des Moines suburb of Johnston when it still rated as a small town. He quips he’s also the third Sid (or Syd) of rock ‘n’ roll, after Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd and Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols.

Flashback 1: July 1998, Axiom Body Piercing, East Village, Des Moines

Slipknot by 1998 had donned its jumpsuits and anonymous numbered identities and was ready to ink its first record deal.

The band signed with premiere metal label Roadrunner Records for what at the time was touted as a $500,000 contract. The band felt so triumphant that they staged a summer signing ceremony in broad daylight on the sidewalk in front of a friend’s tattoo parlor, Axiom Body Piercing—at that time situated in the East Village within eyeshot of the State Capitol.

Twenty-four years later, the band’s forthcoming album will fulfill that commitment to Roadrunner—none too soon for Slipknot.

“The Roadrunner that I fell in love with … has not been an entity for a long time, let alone the people I fell in love with that helped break Slipknot,” Crahan says. “So why would I worry about wasting any of my time on this planet with people that don’t even understand me?”

Taylor says that the band was shorted on its percentage of CD sales by a contract clause that became apparent only later.

Like many acts, Slipknot has diversified its revenue streams with a variety of sponsored merchandise, from boutique whiskey to jigsaw puzzles. Wilson’s head recently was scanned to produce a NFT (non-fungible token, part of the cryptocurrency boom). “We’re king pirates,” Taylor says. “We make our own bread. We do our own thing.”

Flashback 2: Aug. 27, 2001, Peeples Music

Slipknot’s rise at the dawn of the new millennium was met with unsurprising condescension from the music and media establishment at large: This grotesque howl hails from … backwater Iowa?

True to its nature, Slipknot taunted skeptics by naming its sophomore album “Iowa.”

“We brought Iowa with us,” Corey Taylor says. “We didn’t leave it behind—we stayed a band from Iowa.” The anticipated release inspired music stores in Des Moines to open at midnight and sell CDs at the first possible minute for fans who at that time lacked streaming, smartphones, or even a first generation iPod. I roamed the city that night as a journalist and still smile at the memory of Sid Wilson rolling up to Peeples Music on a scooter to purchase his own copy of “Iowa.” (Peeples was located at the northwest corner of University Avenue and 42nd Street, current site of Little Caesars.)

When I shared this memory with Wilson, at first he balked at the word “scooter” uttered in the same breath as his name. He considers himself a connoisseur of more powerful motorcycles. But after reconsidering he laughed to remember he had borrowed a Honda Express scooter from a friend because its model name was the “Iowa”—too appropriate to pass up for his night’s ride circulating among record stores to bask in the excitement of a young band conquering the world.

Flashback 3: August 2010, Sound Farm recording studio, outside of Jamaica, Iowa

Three months after Paul Gray’s death I joined Joey Jordison at a rural Iowa recording studio (now an Airbnb) during a night’s rehearsal with his side project Murderdolls. It was the rural setting where Slipknot recorded its 2008 album “All Hope Is Gone.”

“Life is definitely a lot more precious now,” Jordison said then. “Music right now, really, when I play it, it’s like I’m playing it for all the people that I’ve lost. I think about them all the time.”

Guitars blared indoors as cows mooed softly in a distant dark pasture. Jordison that night reminisced about playing in June 2009 in front of 80,000 fans at England’s Download Festival—a cherished mental snapshot that for him crystallized the fleeting experience of life in Slipknot.

We stared into the rural summer stillness from the back patio. Eventually, Jordison wiped away tears, shook off the melancholy and said it was time for him to go back inside and get ready to rock.

Some 30,000 Slipknot fans, affectionately known as “maggots,” turned out for Knotfest last year. Photographer: Anthony Scanga.

Flashback 4: Sept. 25, 2021, Knotfest Iowa, Indianola

The next generation of maggots is on the rise thanks to Griffin Taylor and Simon Crahan. These sons of Slipknot have launched their own metal band, Vended.

No other platinum act—Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Kiss, Metallica, etc.—has serendipitously spawned its own genetic spinoff, Crahan points out with pride. Both Slipknot dads say they didn’t steer their sons into music. If anything, they filled the kids’ heads full of cautionary tales. Taylor says the weight of expectations means Griffin has it “three times harder than I had it.”

Taylor watched from the wings as Vended took the stage as an early opener at Knotfest Iowa. Instead of Griffin handing his dad bottles of water between songs, their roles were reversed.

“I was bawling my eyes out,” Taylor says. “I was just so ecstatic and proud.”