Written by Jim Duncan

Written by Jim Duncan

Photos by Duane Tinkey

Painter Brent Holland’s studio in downtown’s Fitch Building is cluttered with the props you might expect of a self-portrait artist: anatomical charts and human skulls, mirrors and Shirley Temple dolls. Then there are the seemingly superfluous jade plants.

“Jade is an interesting plant,” he says. “I keep it around to remind me that the more you abuse it, the heartier it gets. Some of us are like that, too.”

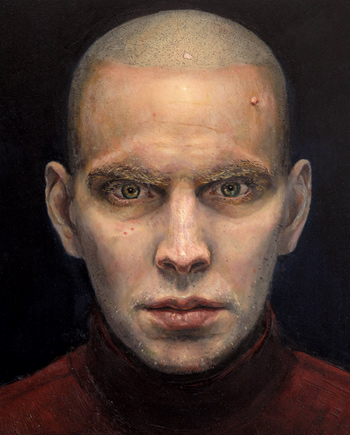

Throughout art history, most self-portrait artists have represented their subjects realistically. Some of Chuck Close’s self-portraits can’t even be distinguished from the photographs he used as models. Other artists flattered themselves. Albrecht Dürer sent his images to various women he wanted to court, looking remarkably like Jesus in some. From Rembrandt and Goya to Van Gogh and Yan Pei-Ming, though, a more intriguing style of self-portraiture emerged from artists who depicted themselves psychologically—depressed and confused, warts and all. Holland parks his easel with them.

“I don’t make happy paintings,” says Holland, an associate professor of integrated studio arts at Iowa State University who lives in Des Moines.

When Holland is standing next to one of his self-portraits, it’s hard to see that the artist and his subject represent the same man. Holland has a boy-next-door demeanor, looking like every student’s favorite teacher. His self-portraits reveal flushed, hairless and stretched skins bulging ominously with sinews, vessels and bones. How did he come to see himself this way?

“The transition to this kind of self-examination came from an existential crisis I experienced—personal baggage that I wrestled with, to address my identity, culture, family traditions and the discomforting nature of reconciliation,” says the Springfield, Mo., native. “Self-portraiture was the most immediate remedy.”

Therapeutic or not, it can arrest viewers.

“If you were only judging Brent by his somewhat maniacal self-portraits, you would be misled. He is a very engaging, articulate and funny person,” says Susan Watts, owner of Olson-Larsen Galleries, which represents Holland. “There is a definite intensity to him, which is probably what drives him to take on the frightening task of self-examination with such fury.”

Holland admits his interest borders on obsession. “Before I was married with kids, I would stay out regularly ’til 4 o’clock in the morning—painting in my studio,” he says.

The artist also believes psychological portraiture was an inevitable progression of his painting. “I began with observation-based training, roomscapes and landscapes,” says the 34-year-old Holland, who earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts in drawing from Missouri State University and a Master of Fine Arts in painting from the University of Washington in Seattle. “Then I self-imposed a transition into more abstract expressions of the same observations.”

Nine years ago, a simple daily routine struck him as a natural extension of observation-based painting. “Looking in a mirror is 98 percent self-examination,” he says. “That translates to psychological and emotional self-awareness.

“What does it mean to paint oneself over and over? Is it strange? It’s definitely a probe that brings intellectual weight down upon you.”

Holland has been concentrating on figurative painting and drawing since then. He admits that his ambiguous relationship with his self-portraits could relate to the conflictive duties of painting and teaching: “Academically, you balance being critical while also being experimental. You need to explain what you are doing even as you enter totally new territory.”

“I get angry if I am not painting,” he adds. “Teaching is a necessity, though.”

Recently Holland has become interested in a psychosis that causes people to lose the ability to distinguish faces. He has teamed up with an ISU psychology professor to make presentations about the disorder and how even healthy people can possess a degree of the affliction.

“I am attracted to faces because in many ways they’re the most familiar thing we observe and also the subject we know the least about,” he says. “There‘s an obvious psychological draw.”