Writer: Tim Paluch

Sound check, Sips and the City.

In less than an hour, Walter and Wagner Caldas, 31-year-old identical twins better known as the Brazilian 2wins, are booked to play three hours of music for wine tasters inside Capital Square this hot summer night.

Wagner, who plays ukulele and runs the sound mixer, can’t figure out why Walter’s violin sounds so scratchy on the speakers. After about 20 minutes, they’ve decided the culprit is, maybe, a faulty wireless violin microphone.

“I’m sure we’ll figure it out,” Walter says.

This nonchalant attitude is nothing new for these brothers from the Brazilian slums, who use youthful exuberance and optimism as weapons against any and all challenges: moving to America without knowing the language after a series of serendipitous meetings; living the lives of struggling artists trying to break out in the music industry; even overcoming an aggressive form of cancer that threatened to take Wagner’s life.

To better understand their refreshing outlook, one must first travel back a few decades, and south a few thousand miles.

Life in the Favela

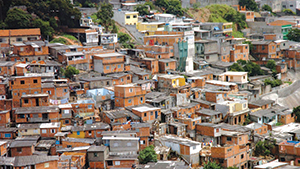

The longest bridge in the Southern Hemisphere connects Rio de Janeiro to Niteroi, a city of half a million people in southeastern Brazil. Niteroi is a financial and commercial center, with modern buildings and shopping malls, but the Caldas family lives in its poorest area—the favela, a Portuguese word that more or less translates to “slum.”

Favelas throughout Brazil are distinguished by their primitive infrastructure and public services, high crime and extreme poverty. Most residents have no diploma. Most boys become men who work a life of hard labor for low wages. They start families and build atop their parents’ homes, often using whatever materials they can find or afford, creating an urban landscape of dirt and brick dotted with pastels and bright colors.

“We had nothing, but at the same time we had everything,” Walter says inside the small apartment near Ingersoll Avenue he shares with his wife, Molly, and new dog, Branca, a gentle pit bull who likes to sleep. He talks over the loud buzz of an air conditioner attached to the wall over the couch, and hums “No Diggity” by Blackstreet as he searches his laptop for photos of home. He shows them off with great pride.

“Everything we are today—the personality, the craziness—is from here,” he says. “Our childhood was everything you could ever imagine. Pure happiness. Freedom.”

The brothers and their friends spent their days running barefoot in the streets, playing soccer for hours, riding bikes down to the water, eating out of the garbage when they got hungry. Kids were everywhere. For a while, the family made trips to a local well for water before their father was able to install a primitive plumbing and water storage system in their home, a small brick structure without glass or screens on the windows.

Wagner says living in the favela is a “beautiful reality” in which people don’t think about money. No one considers themselves poor.

“There, you are just living,” he says. “If you don’t know what else is out there, you don’t think about what you don’t have. Then when you see what is possible (outside the favela), you start giving importance to things like money. So

sometimes there is a price to pay for having that knowledge.”

As they grew into teenagers, the brothers listened to American pop music—Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston and the Backstreet Boys. They memorized every

word of every song but had no idea what any of them meant.

Walter started an all-boys dance crew called the Big Boys, the only English he knew at the time, and they performed at street parties in exchange for food off the grills.

Around them, other boys fell into drug trafficking and street gangs. “We had a lot of friends get killed,” Walter says.

“My mom used to take us to see their bodies. She would wake us up and show us, and say ‘See why he’s dead?’ And there was nothing, no cops, just a body, fresh on the street.”

Music kept the twins from any chance of a turn toward this life.

Their father, Jonas, was placed in an orphanage as a boy after his mother could no longer afford to take care of him. There he was assigned a trade: furniture maker. He started making wooden toys, then he built his first guitar, then his first violin. But as his family grew he couldn’t afford to work on his craft, so he drove a truck full time for more than a decade, scratching together enough money to open a shop in a garage next to his tiny home.

Eventually, he started fixing instruments for an orchestra that had sprung up in the favela as a way to help keep kids off the streets. In exchange, his twin boys took lessons. The program took off, and the boys’ natural talent quickly became apparent. Walter and Wagner were the first students to play violin. They joined the orchestra when they turned 12 and began traveling outside the favela to perform.

“And who listens to classical music?” Walter says. “Rich people. So then we started crossing the margins of where we were born and raised to the rich areas.”

The orchestra played for celebrities and dignitaries. The gregarious twins and their high-energy takes on revered classical music stood out. After a performance in Rio in 2006, a National Public Radio producer spent the day at the family’s home to tell their story.

The brothers began to imagine a life outside the favela.

“Art in general, it takes you somewhere, somehow,” Walter says. “It gave everyone a vision of the world they didn’t have, including me.”

Thousands of miles away, in a place they’d never heard of called Iowa, someone heard their segment on NPR.

Making It In America

In the summer of 2006, the World Food Prize announced its laureates, people recognized annually for leading advancements in the quality or availability of food in the world. The three winners that year each played a prominent role in transforming an infertile region of Brazil into productive cropland.

As Ambassador Kenneth M. Quinn, the World Food Prize president, and his team were planning the organization’s fall event honoring the laureates, he heard the NPR segment on the Caldas twins.

“I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, what an interesting story,’ ” Quinn recalls. He decided to bring them to Iowa to perform at the ceremony. The World Food Prize helped the twins get visas and paid for their travel and three days’ stay at the Hotel Fort Des Moines.

Backstage, the twins wondered why all the other performers were so tense. “We figured out what to play like 10 minutes before,” Walter says. They weren’t nervous and didn’t rehearse. The brothers traveled more than 5,000 miles to play just 2 1/2 minutes of music—Walter on violin, Wagner on ukulele.

“They dazzled. They had the energy of youth; they just had this verve to them,” Quinn says. “You could just see it and feel it in the room.”

Benjamin Allen, then the president of the University of Northern Iowa, approached them through a translator after their performance and, on the spot, offered them a full scholarship to study music at the university.

“We thought it was just talk,” Walter says. “A month later we started receiving stuff in Brazil from UNI, everything in English, with pictures of dorms, and I was like, ‘Oh my God, we’re really going.’ ”

They hid the brochures and letters and found help filling out all the applications and paperwork before telling their parents they were moving to America. “They were afraid for us,” Walter says. “They were thinking we were just going to another favela, in the United States.”

Neither could speak or read English. People in Brazil made them signs written in English asking for help getting to their gates and to taxis, which the twins held as they walked through airports.

English classes on campus were more difficult than they expected. “We couldn’t even ask for help. We could never tell

the teacher, ‘Hey, I didn’t understand a word you just said,’ ” Walter says. He learned the language and adjusted to American life a bit better than Wagner, who often missed home and felt self-conscious about his language.

But they never let each other get low enough to regret their decision to come to America. “Having each other was a big part of it,” Walter says. “We never let each other feel sorry about anything in our lives.”

At every challenge, they brought with them the carefree attitude toward life—a mix of unbridled optimism and naiveté—one learns growing up in the favela. Even as they struggled with classes and the language, the brothers danced at clubs, gave hugs to strangers, made dozens of friends and became known around campus as “the Brazilian twins.” They soaked up the attention.

At a bar one night, the brothers met TC VanHooreweghe and became fast friends, spending time with his family at holidays. “It sounds cheesy or cliché, but they are so magnetic,” VanHooreweghe, now the Brazilian 2wins manager, says. “When you are around them, people get out of their comfort zones. They break the ice immediately and you can see a person change.”

Music became more important than class. Both are musical savants and only need to hear a song once before they can play it themselves without ever reading the music. The brothers performed at university events, but also started the band, the Brazilian 2wins, where they put their own classical spin on the popular music they grew up loving back home.

Shows were high-energy, frenetic, a mix of covers and original music. Walter and Wagner bounced and danced around stage with their violin and ukulele (and backing band, a drummer and bassist), interacting with the crowd between songs. The Brazilian 2wins grew popular around Cedar Falls and Waterloo, then started touring throughout Iowa and the Midwest and eventually found success on the college market.

They dropped out of school and became full-time musicians. Both met their future wives. The dreams of those two boys in the slums of Brazil memorizing Michael Jackson and Justin Timberlake songs were coming true.

The 80/35 Music Festival booked them to perform at the 2015 festival, which would put them in front of a crowd of thousands. The downtown Des Moines concert would be the most important show of their careers.

A few days before the show, Wagner stepped out of the shower, wiped the steam off the mirror so he could shave, and saw a lump on his chest.

‘Just Another Crazy Adventure’

Thirty minutes to show time at Sips and the City, and the brothers are changing into their ivory tuxedo jackets and eating Jimmy John’s sandwiches in a makeshift dressing room near the elevators and bathrooms of Capital Square.

Wagner removes his shirt to show the scars. Near his left shoulder, a radiation burn. Below his right collarbone, a chemotherapy port remains implanted in his chest. He went through 31 brutal rounds of chemo over nine months once doctors discovered the tumor: a very rare, very aggressive form of cancer called Ewing’s sarcoma.

For about a year, Wagner had suffered from pain and numbness in his hands, fingers and arm. Doctors thought it was a nerve issue and performed surgery on his ulnar nerve. The pain remained, then worsened. He started taking painkillers. He stopped sleeping.

He and his wife, Tracy, began to fear something more ominous was causing the pain. When they saw the lump last July, fear became reality. Doctors performed a day’s worth of tests, then sat them down in a room at University of Iowa Hospitals and delivered the news.

“My wife started bawling,” Wagner says, “but I said, ‘OK, so what do we do now?’ I immediately went there. I knew I was in a different game now. I have a way of simplifying everything in my mind, and the worst thing that could happen to me in this whole deal is for me to die. People die every day. I won’t be the first or the last person to get cancer.”

Treatment needed to be aggressive. If the cancer spread to his bones, Wagner’s chances of survival shrunk significantly. Doctors told him they would likely have to amputate his left arm. They even set a date for the surgery, Sept. 3. Wagner thought he would never play the ukulele again, so he went home and downloaded music to teach himself the piano.

In addition to his wife, Wagner told only Walter, and the Brazilian 2wins performed at 80/35 in what the brothers knew could be their final show together. In photos, Wagner can be seen shaking his hand, in pain but trying to hide it. Walter says he looked at his brother throughout the performance and saw him as happy as he’d ever seen him onstage.

The first chemotherapy floored him. “I thought I was going to throw up to death,” Wagner says. All his hair fell out. His beloved afro peeled off like a wig. He spent nine months in treatment, rotating between 48-hour and five-day chemo drips.

“It was our whole life,” Tracy Caldas says. “At one point we thought like it was nine years and not nine months.”

Fans raised more than $30,000 online for him. The cancer responded well to treatment. Doctors canceled the amputation.

Through it all, he kept the upbeat, positive attitude, viewing the entire ordeal as “just another crazy adventure,” a bump in the road on the way to their American dream. This was not an act. He played practical jokes on his friends and family and recorded videos of himself dancing in the hospital hallways. His friends back home in the favela shaved their heads in solidarity and sent photos.

Every time Walter, back home in Des Moines, would feel his mind creeping to dark places, he called Wagner, who would cheer him up from his Iowa City hospital bed.

“There is something you have to know about us to understand this reaction,” Walter says. “We are very happy and try not to ever worry, and we believe in energy, and believe that negative energy brings more negative energy brings more negative energy.

“It’s just the way we grew up,” he adds. “It drives our wives crazy.”

The band played on in Wagner’s absence, but he made a surprise appearance at a Waterloo concert once treatment ended in the spring, walking onto the stage—still bald, and thin—with his ukulele while Walter sang “Lean on Me.”

He goes back for tests every three months—the first one came back clean—and knows the chance of the cancer returning is as high as 40 percent. But still he is undeterred.

“Most people get depressed, and that’s why I think they lose,” he says. “They get afraid and it overwhelms them. I never look at the negative stuff. I am gonna make it. It’s just cancer. If it comes back, I will beat it again.”

The brothers cut the tags off each other’s new jackets and walk out to the small stage. The crowd is starting to swell as they begin playing a 10-minute improvised version of the Daft Punk and Pharrell Williams song “Get Lucky.”

The chorus begins with these lyrics: “We’ve come too far, to give up who we are.”