Artist Jim Ochs says he painted the 36-by-61-inch “Tet, 1968,” as a “protest against all wars,” not just the Vietnamese conflict in which he served and from which he drew the painting’s title. Ochs worked on the acrylic and watercolor crayon painting from 1996 to 2015.

Writer: Michaela Mullin

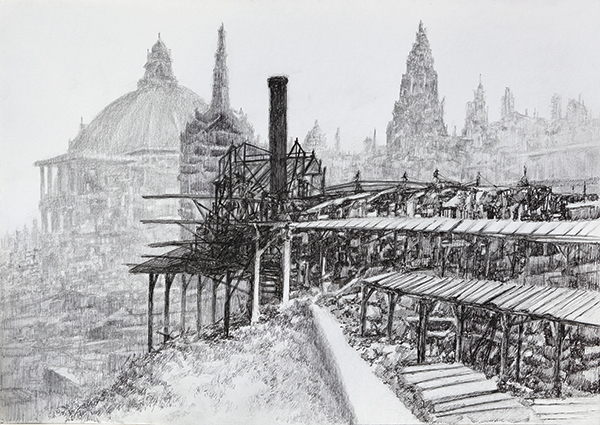

Jim Engler, “Cityview” (detail) (2016); ink and graphite, 12-by-17 inches.

A new exhibit at Polk County Heritage Gallery springs from a conversation between neighbors that might seem as unexpected as the exhibit’s subject: visual art and military veterans.

During a Des Moines Metro Opera patrons’ event at Moberg Gallery last fall, gallery manager Ryan Mullin and Skip Manus, a chaplain with the Army National Guard, were catching up when Manus mentioned something that immediately captured Mullin’s attention.

“Skip said that he knew soldiers who were making art but were reluctant to share it with others,” Mullin recalls. “He told me that veterans are sometimes especially hesitant to expose that creative part of themselves to fellow vets.”

For Mullin, who says “art is about connection,” it seemed that these works and the artists who make them deserve to be seen. It’s important for the public to have the opportunity to interact with the works, Mullin says, explaining that “being open to art and artistic sensibilities helps us make deeper connections than we think exist on the surface—deeper than our misconceptions, prejudices or stereotyping would otherwise allow us to explore.”

Moberg Gallery represents several artists who are veterans, so Mullin was inspired to start planning an exhibit. He decided to also reach beyond the gallery’s artists to include works created by other veterans.

The exhibit, “Worth Fighting For,” is an “interesting format for citizens to connect with and support veterans,” says Manus, the Guard chaplain. “After all, less than 1 percent of the population wears a uniform, and only half of that actually goes to war. Joining is almost never about a political bent but rather to serve the citizens. This show can help connect the dots to the people they were serving.”

Of course, there’s a long history of visual artists in the military—think Jasper Johns’ 1951 conscription into the Army, for example—as well as official war artists in the American military since 1917. Iowa’s own Grant Wood was drafted into the Army as a camouflage painter in 1917.

On the following pages, three artists who are featured in the exhibit share some of their stories and their art.

Jim Ochs

Jim Ochs, “Mr. President” (2015-2016); acrylic on paper, 18-by-16 inches.

After graduating from Colorado State University in 1969, Jim Ochs found himself drafted and on his way to Southeast Asia where the Vietnam War raged on.

As an Army cartographer, he created charts with information obtained by reconnaissance patrol units. Whenever he could, Ochs continued to draw, sketching soldiers, Vietnamese civilians and scenes that caught his eye.

Following his one-year tour of duty, Ochs went to the University of Iowa, where he studied with Mauricio Lasansky and earned an MFA in printmaking and drawing. He still lives in Iowa City.

A 19-year project, “Tet, 1968” (pictured on pages 184-185) is an acrylic and watercolor painting that Ochs began in 1996 as a “protest against all wars,” he says. He adds that the painting, which he completed in 2015, follows in the tradition of Francisco Goya and Pablo Picasso, and their powerful war works, “The Disasters of War” series and “Guernica,” respectively.

He is delighted by the opportunity to exhibit “Tet, 1968,” which reflects the Tet Offensive, a historic assault on multiple sites in South Vietnam that is now seen as a turning point in the history of that war.

“Not all shows want work like this,” he says. The painting’s haunting reaper-like figures and grim violence are set before a horizon of flames—“a burning city in the background,” Ochs says. All of these elements serve to create a field of many types of battle, both global and personal: historic, timely and consequential, as well as physical, psychological and spiritual.

His military experience “has no relation to my work now,” Ochs says. His deep historical, literary and political interests are evident in his new portraits of subjects ranging from Jean-Paul Sartre to Donald Trump (pictured, left). He employs a layered method—often cutting the works into strips and manipulating them—that both covers and discloses texture and color.

These abstract portraits capture the spirit of their subjects as much as the physical image, and they expose a truth of art making—a work could continue to develop indefinitely, but the creator must decide on a moment of completion. Ochs’ outlook on art, as well as life, is reflected in a quotation he loves by his fellow artist in arms, Jasper Johns: “Take something and do something to it, then do something else to it.”

Jim Engler

When Jim Engler joined the Air Force as an 18-year-old in 1954, he had a plan: Enlist, go to college on the GI Bill to study art, and become an artist or professor of art. It was a plan he stuck to: After returning home to Omaha and earning a BFA from the University of Nebraska and an MFA from Drake University, he joined Grand View College (now, University), where he taught art for 34 years.

“All young people should have time for maturing before they go to college,” Engler contends, recalling his three and a half years as an Air Force jet mechanic stationed in Portland, Oregon. “I learned creative problem-solving,” he says, a skill that carried over into his years at Grand View, where he taught a creative problem-solving class.

During basic training, Engler drew caricatures of airmen and drill instructors, and in Portland, he drew cartoons for his base newspaper.

Once discharged, he gave up jet engines for pens and pencils. People often get diverted from the artistic path due to fear of failure, he says. And in his case? “Failing never entered my mind,” he says. “I just forged ahead.”

His graphite and ink drawings appear as stunning cityscapes that feel both historical and futuristic, simultaneously. “These naturalistic drawings use counterpoint [multiple points of interest], and they are very detailed—intricate and fine—with the buildings all scrunched together,” he says.

“Viewers have commented on these drawings,” he says, “noting that they see ruins in the foreground and new or intact buildings in the background.” This juxtaposition creates what is reminiscent of a post-blitzkrieg scene.

However, Engler says, “my artworks are not informed by my time in the military.” The closest he got to the heat of military action, he says, involved an engine fire in a hangar: “I was recognized for being one of the airmen who helped put out that fire.”

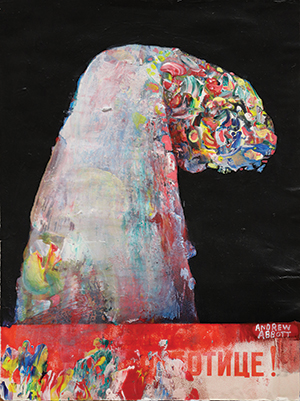

Andrew Abbott

As he was nearing graduation from the University of North Carolina, Andrew Abbott resolved to eventually become a working artist.

However, in 2004, three years after the war in Afghanistan began, Abbott was traveling and following whims. “I was in an adventurous mood,” he says.

He considered joining the Peace Corps, the circus and the military. At age 24, he enlisted in the Army, opting to become a medic rather than a combatant. He prepared for deployment to the Middle East, but his service was confined to California and Louisiana.

During a year in the Army, Abbott created many small works—“a stack of 8 1/2-by-11-inch paintings on paper,” he says.

Abbott’s artworks focus on the figurative within the landscape. In his paintings, which manage to exhibit both radiance and the darkness from which it emits, Abbott often renders the same figure or object in repetition. This very act uncovers the truth, or falsity, of sameness—that no two things are alike.

The New York-based Abbott believes his time studying anatomy and bodily injury as a medic may have influenced what he calls “the transparent and internal aspects of my paintings. In them, you can always see the interior of the subjects I paint.”

When he joined the Army, Abbott recalls, “I had all kinds of preconceived notions about what the soldiers would be like. I soon learned that they are a very diverse group, with a plethora of interests and backgrounds. We all wore the same clothes, but we were a very assorted bunch of people.”

Artists Exhibiting In ‘Worth Fighting For’

Andrew Abbott:

A New York artist, Abbott was an Army combat medic for a year. He works in acrylics, on an array of substrates: military forms, polystyrene foam, printing screens and items he gathers from the streets of Brooklyn.

Mike Amundson: A retired Army officer who lives in Johnston, Amundson studied graphic design in college. He is interested in images that result from the collision of culture and politics. This is his first public exhibit.

Jim Engler: Engler lives just outside Peru, Iowa. A former jet engine mechanic in the Air Force, Engler creates works that are “semi-abstract,” because he is interested in the viewer experiencing the creative journey with him, and assisting him in completing the stories his artwork tells.

Tom Moberg: Moberg is a nationally recognized multimedia artist based in Des Moines. He served as a Navy petty officer at the Naval Destroyer School in Rhode Island, where one of his jobs was drawing training aids for instructors.

Jim Ochs: Based in Iowa City, Ochs was drafted into the Army in 1969 and spent a year in Vietnam. His artwork focuses on media and composition that imbue the subjects with the most power. For example, in creating his work “Aleppo,” which addresses the Syrian civil war, Ochs used Black Cat firecrackers to create an explosion-ravaged surface.

Bart Vargas: Council Bluffs artist Vargas served for six years in the National Guard. His work today focuses on using recycled materials to create sculpture, paintings and installations that probe everything from personal identity to political outrage. To learn more about Vargas, read the story published in the new issue of ia, dsm’s sister publication, here.