Writer: Jane Schorer Meisner

Photographer: Duane Tinkey

Iowans are about to get a schooling on the hidden talents of a famous native son.

Fifty-five years after the death of two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist Jay N. “Ding” Darling, the breadth of his talents, contributions and artistry is being revealed and celebrated from a new headquarters in downtown Des Moines’ growing Mainframe Studios.

Sam Koltinsky, a documentary film producer, made a commitment to Darling’s grandson to tell the world about Darling and to preserve his legacy. In the process, Koltinsky, 64, has become a nationally recognized expert on Darling, who was best known by the contraction of his last name, “D’ing.”

“I have lived in different places around the world, and I’ve never found anyone like Darling, ever,” Koltinsky says. “He was someone who had the visionary abilities to navigate change using so many different talents.”

Darling was a woodcutter, sculptor, designer and fine artist—and a leader in conservation efforts. In Des Moines, though, he’s best remembered as a longtime editorial cartoonist for The Des Moines Register, where he worked from 1906 to 1949, with the exception of two years at The New York Globe and 20 months in Washington, D.C., where he served as head of the U.S. Biolgoical Survey in the 1930s.

“That man pulled everything from himself intellectually, physically, mentally and spiritually, to make things happen,”

Koltinsky says. “There are very few people who can do that.”

Koltinsky’s work on a documentary about Sanibel Island, Florida, where Darling had a winter home, led him to explore the J.N. “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge there. That led him to meet Darling’s grandson, the late Christopher “Kip” Koss, and become fascinated with his stories about Darling.

In 2012, Koltinsky’s production company, Marvo Entertainment Group, completed its first documentary on the artist, called “America’s Darling: The Story of Jay N. ‘Ding’ Darling.” Later, he worked on cataloging and digitizing nearly 4,000 original printing plates of the cartoons of Darling and his successor, Thomas Carlisle, from The Des Moines Register.

Koltinsky also created a traveling exhibit, “The Hidden Works of Jay N. ‘Ding’ Darling.” That exhibit of artwork

and personal artifacts consumes 2,000 square feet when fully staged.

Now, Koltinsky is director of the newly created Jay N. Darling Center in Des Moines.

The Darling Center

The center could have been established in any number of locations where Darling had his footprint, Koltinsky says. But Des Moines was his longtime home (though he spent winters in Florida).

“Living in Des Moines now, I understand why

Darling kept coming back here and loved it so much,” Koltinsky says.

The center at Mainframe Studios, located at 900 Keosauqua Way, houses Darling keepsakes provided by people from around the country.

“The basis for all this is being built the way Darling would have built something, by bringing people together,” Koltinsky says.

The center will have a grand opening in late spring (the exact date was unknown as of press time). Until then, it is open by appointment from 2 to 7 p.m. Wednesdays through Saturdays. There is no admission charge.

Through the center, a curriculum for young people titled “Our Outdoor Heroes” will be available in early summer. Koltinsky continues to explore establishing a Jay N. Darling Institute, which he envisions as a university-based curriculum whose content will examine Darling’s legacy as the core of programs in journalism, media, ecology, agriculture, political science, law and environmental studies.

An Artists in Studio program will connect artists locally and nationally to study Darling’s artwork. Early this year (an exact date was unknown at press time), works from various artists—including prints, mixed media, murals, watercolors and glasswork—will be showcased on three floors of gallery space in the R&T Lofts, the building where Darling spent most of his career. Historical images from the Register staff also will be displayed.

“We are connecting the past with the present at R&T Lofts,” Koltinsky says.

The Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation is helping to connect Koltinsky with people who will be passionate about supporting the Jay N. Darling Center, says its president, Joe McGovern.

“Sam has a vision, not only to recognize Darling, but to inspire people to follow in his footsteps,” McGovern says. “INHF is happy to play a small part in this project.” INHF is accepting donations on behalf of the Darling center, which is currently working toward establishing a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt nonprofit status.

The center’s collection is impressive, McGovern says. “One of the pieces most meaningful to me is the first Duck Stamp. Darling was able to use his talent as an artist to effect major change for conservation in this country.”

A Treasure of Sketches

When Koltinsky began researching Ding Darling for his initial documentary, he was surprised to learn that the cartoonist had painted watercolors and drawn countless sketches.

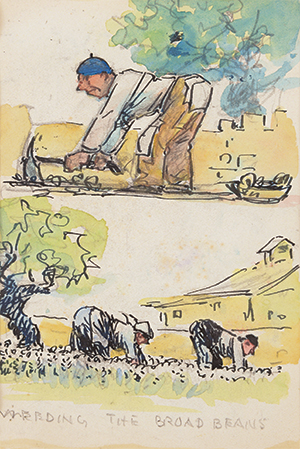

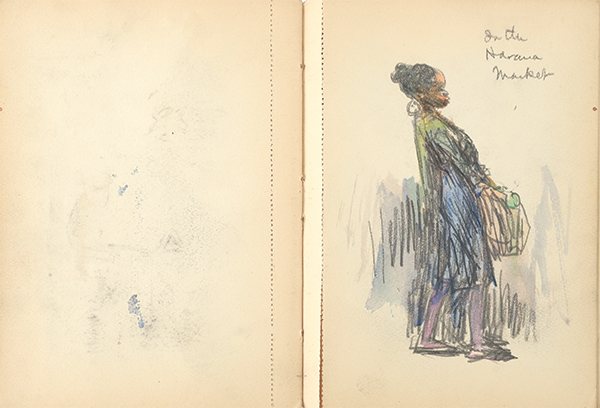

“Darling always had a sketchbook with him,” Koltinsky says. “Always.”

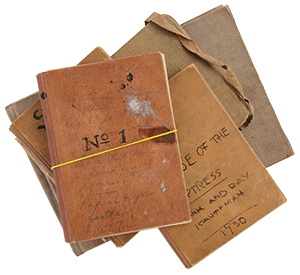

Koltinsky is releasing a collection of Darling’s 4-inch-by-6-inch sketchbooks—some now more than a century old—for public view for the first time. Koltinsky calls them “an insight into Darling’s soul.”

Darling was a world traveler, and he drew sketches of destinations he visited and people he encountered—always with accompanying notes, Koltinsky says.

“Sometimes he would dictate to his assistant, and they would put together a log of their travels,” he says. “That was when he was relaxed and having fun, when he wasn’t under pressure to create.”

Some of the sketchbooks will be viewable in digital format on the center’s website, jayndarlingcenter.org. Koltinsky also plans to show the sketchbooks by appointment and at monthly open houses at the center.

“I like to speak to groups about all that we are doing, and

I like sharing our treasures,” he says.

Funding the Project

Koltinsky has a goal of raising $3 million in the next few years for the operation of the Jay N. Darling Center.

“I’m pretty good at persuading people to write a check for the right cause,” he says. “But I need the community. I need people to join in and help me champion this.”

Koltinsky, who owns the rights to Darling’s works, produced a limited edition of 25 prints of a Darling watercolor that he has sold for $10,000 each.

“There are other works to be released at $299 and up,” Koltinsky says. Darling-inspired items created by other artists will be sold at the center.

Also, the first 10 donors of $100,000 or more will receive one of Darling’s personal paintbrushes that Koltinsky acquired from the artist’s grandson.

“I like the idea of Darling helping to fund his own center and institute through his creativity,” Koltinsky says.

The Many Talents of Ding Darling

Ding Darling’s grandson used to tell Sam Koltinsky that Darling needed to be viewed as more than just a cartoonist.

“So many people know him from his 15,000 or 16,000 editorial cartoons, but there was so much more,” Koltinsky says.

Darling was born in 1876 and grew up in Sioux City. Although he loved drawing and was seldom without his sketchpad, his goal was to become a doctor.

He enrolled at Yankton College, but he was expelled for taking the president’s carriage for a spin without permission. At Beloit College, he was expelled for reasons that may have been poor attendance or failing grades—or the fact that he had drawn caricatures of professors for the college yearbook.

“He gave his parents a run for their money,” Koltinsky says.

After eventually earning a degree from Beloit College in 1900, Darling took a job as a reporter for the Sioux City Journal to earn money for medical school. When he was unsuccessful at snapping a photo of an obstinate trial lawyer, Darling drew a sketch of the attorney instead. That began his cartooning career, and his drawings became a daily feature in the Journal.

Darling rose to national fame at The Des Moines Register, which he joined in 1906. In the 1930s, he also became deeply involved in conservation.

“Ding Darling gained notoriety at a turning point in the conservation movement in this country,” says Joe McGovern, president of the Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation. “He was a prolific cartoonist, but his themes often returned to conservation and natural resources. He was so influential in the movement that he was appointed by President Franklin Roosevelt as head of the U.S. Geological Survey, which eventually became the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.”

Darling has a presence at the Iowa State Historical Museum, says museum curator Leo Landis. “We featured Ding Darling in the ‘Delicate Balance’ exhibit for his nationally significant role in soil conservation and wildlife habitat protection,” Landis says. “He had many contributions, but one that persists and protects habitat is the Federal Duck Stamp Program. Darling illustrated the first Federal Duck Stamp in 1934, and the program continues to generate more than $1.3 million a year.”

The museum has four large original Darling cartoons on display plus a bust of Darling, Landis says: “We also have a 1934 Federal Duck Stamp and illustration of the image by Ding in the exhibit.”

Darling’s fans included presidents from Theodore Roosevelt to Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman. He was close friends with prominent figures, including President Herbert Hoover and environmentalist Aldo Leopold. Such relationships represent what Koltinsky says was Darling’s greatest gift.

Darling, who died in 1962, “was a mastermind at bringing people together, having a vision and partnering through cooperation to make things happen,” he says. “Darling shows us who we can be at our best, when we do work together and cooperate.”

Darling’s sketchbooks are loaded with charming figures like “the baker’s boy” (on the cover), field workers or the woman “in the Havana market.” He sometimes sailed with wealthy friends and captured the water gracefully. For example, a sailboat ghosts along (above right), powered by “a light beam breeze and everything she’s got on her.”

Exhibit

“The Hidden Works of Jay N. ‘Ding’ Darling” traveling exhibit will be at Drake University’s Cowles Library from March 26 to May 31. The exhibit will be accessible to the public during regular library hours.