Writer: Michael Morain

Photographer: Duane Tinkey

RICK TOLLAKSON

The Convert

“I had no clue what a water trail was. To me, the water was just something to look at as you bike by.”

That’s what Rick Tollakson thought until one muggy day a few summers ago, when he found himself in a kayak, paddling through a leafy corridor that he never knew existed. The guided tour of Beaver Creek started near 86th Street, up where it meets Northwest 70th Avenue, and finished with a climb up a weedy bank—gear and all—north of the interstate near Merle Hay Road.

“You felt like you were in a different world—and you’re in Johnston,” says Tollakson, president and CEO of Hubbell Realty.

The Des Moines Area Metropolitan Planning Organization had recruited Tollakson to chair its Water Trails Steering Committee, and all it took was that trip down Beaver Creek to turn him into a believer. Since then, he’s spread the gospel during similar paddle tours with other civic and corporate leaders.

Sometimes he even baptizes them. At the end of one trip, when he was pulling his canoe out of the Raccoon River, he lifted the front end a bit too early and accidentally tipped former West Des Moines City Councilman Rick Messerschmidt into the water.

Tollakson felt bad about it, but it served a point. “You’re not going to die if you fall in,” he says. “Believe me, I’ve been in these rivers a few times and I’m still here.”

He’s jumped into some other rivers, too. Tollakson and other steering committee members visited Columbus, Georgia, where kayakers paddle some of the largest rapids east of the Rockies on the longest urban whitewater course in the world. Advocates for a similar course in Des Moines say it could be part of a whole adrenaline-pumping adventure park, with zip lines, climbing walls, and the proposed skate park near Wells Fargo Arena.

“We have to get ahead of the curve,”

Tollakson says. “I can’t say it enough: This could have a huge impact on our ability to recruit new people to Iowa.”

When he and the committee visited Boise, Idaho, a while ago to check out its mechanical surfing wave, he struck up a conversation with one of the surfers awaiting a turn on a weekday afternoon.

“Turns out the kid was from Cedar Falls. And the guy running the wave machine? He was from Marshalltown,” Tollakson says. “We’re losing folks to places like Boise because they have a lot more going on.”

STACI WILLIAMS The Teacher

There was a snapping turtle. There were owls. There were other animals, too, that Staci Williams spotted among Central Iowa’s waterways last summer.

But nothing ambushed her quite like the baby catfish she found. Inside a mussel shell.

“When I opened it up, I don’t know which one of us was more surprised,” she says.

She tells the story with a grin and a sense of wonder that make clear why she used to be a fourth-grade teacher, for a few years in Myrtle Beach, S.C. But a class project on sea turtles led her to conservation advocacy, which led her to a master’s degree in environmental law and policy, and, eventually, to a job with American Rivers.

The nonprofit helps communities reconnect with their rivers to solve both environmental and economic problems. Williams was skeptical at first.

“Could that really spur all of these community benefits?” she wondered. “But it did.”

Her first project focused on North and South Carolina’s Waccamaw River, where little changes led to bigger ones. More recreation (boating, fishing) led to more business (outfitters, restaurants) and more political clout to enact ordinances that encouraged conservation and cleaner water.

American Rivers sent Williams to work on projects across the country—Arizona’s Verde River and Colorado’s Eagle River, among others—but the Huxley native eventually wanted to return to Iowa. She moved to Des Moines and signed on last year as a grant writer and water quality specialist for ISG Engineering and Architecture.

She says colleagues tease her because she is “an odd fit for an architecture and engineering firm.”

But lately her teaching skills have come in handy. She spent the spring presenting water trail proposals to city councils, watershed management authorities and other civic groups. She explained maps, renderings, conservation strategies and other plans for no fewer than 145 sites along nine waterways, which she can rattle off without hesitation.

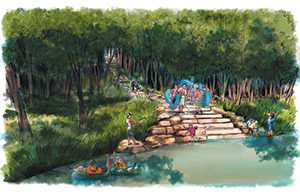

While downtown’s dam debate has grabbed most of the attention, Williams has high hopes for waterways throughout the region. Johnston’s Beaver Creek could become a popular paddling and floating route for families. Pleasant Hill could become a launching site for trips down to Yellow Banks Park and Lake Red Rock.

Everywhere in between, people can use the water trails to swim, paddle, boat, fish or just skip stones. Even sitting on a riverside bench helps people relax and reawaken their senses.

As she puts it, “There’s a reason all those nature recordings have some sort of flowing water and chirping birds.”

Karl Keeler

KARL KEELER The Transplant

When Karl Keeler and his family moved to Des Moines this past winter, his 15-year-old son, Cameron, asked why nobody surfed the Des Moines River.

It’s an obvious question—if you’ve grown up in Idaho.

Before Keeler became the president of Mercy Medical Center in January, he and his wife, Kristen, and their five kids lived in suburban Boise and spent a good chunk of their free time on the Boise River, which starts with melting snow in the Sawtooth Mountains and joins the Snake and Columbia rivers in their westward rush to the coast. Along the way, the Boise cuts through the Idaho state capital, where folks like the Keelers float, fish and, yes, even surf from early spring to late fall.

A daily parade of buses shuttles locals and visitors upstream with kayaks, canoes and inner tubes. “Anything that floats,” Keeler says. “We just used stuff that you can buy at Target.”

The trip downstream usually takes a couple of hours, depending on how many stops you make at swimming holes, rope swings or the come-as-you-are restaurants along the way. When the river hits downtown, it spills through a whitewater park with a dam that engineers can adjust—lower for kayakers and higher for surfers, who glide back and forth on the churn.

Keeler’s oldest son, Jackson, 17, surfed the river all the time with his friends. He was surfing on a mountain lake during last summer’s eclipse.

“When I told people I was leaving Boise for Des Moines, everybody asked, ‘What do you do there?’ ” Keeler says in his office at Mercy. He points to the blue sky out the window: “In Boise, it’s like that every day.”

Boise has some of the lowest salaries in the country, he adds, but that didn’t stop him from hiring talent at the hospital where he used to work. Health care pros with high-demand specialties tend to love the city and its outdoorsy appeal. The ski slopes are just half an hour up the road.

Hiring is a tougher task in Des Moines, where a big part of Keeler’s job is attracting and keeping enough employees to fill Mercy’s 7,500 jobs. River trails aren’t the only solution, he says, but they sure can’t hurt.

“For a Midwest community, this could absolutely set us apart,” he says. “When they said the plan would get going in five years, I thought, ‘Oh, how can we get this done sooner?’ ”

He and his wife immediately supported the water trails plan when they first heard about it at a Greater

Des Moines Partnership dinner. And so did their amphibious kids, who are too young to remember the old “Surf Iowa” T-shirts from the 1980s. Now the idea seems less absurd.

“I still have two huge stupid boxes filled with rafts in the garage,” Keeler said. “We should have given them away before we came here, but maybe now we won’t need to.”

Water Trails Overview

Water Trails Overview

Advocates for Central Iowa’s $117 million water trails project have spent the last few years laying stepping-stones, but now comes the leap of faith: Public and private partners need to decide whether to make any of the plans actually happen.

So let’s back up to see how we got here: For thousands of years, rivers and creeks have supplied Central Iowa with water, food, transportation routes, energy, beauty and all the other stuff that make life possible.

But during the past 50 years or so, most people have disconnected from these waterways to the point that when they think about them—if they think about them at all—the first words that pop into their minds are “flooding” and “nitrates.” Rivers have gotten a lot of bad press since the floods of 1993.

Recently, however, the Des Moines Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) has led various regional efforts to see how Central Iowans can make better use of nine waterways for various environmental, recreational and economic purposes. Those waterways are the Des Moines, Raccoon, North, Middle and Skunk rivers, along with Beaver, Fourmile, Walnut and Mud creeks.

The MPO’s early research led to a slew of brainstorming sessions and public surveys that eventually generated a wish list of more than 80 individual projects scattered among the waterways, which total about 150 miles. Eventually, that wish list turned into the Greater Des Moines Water Trails and Greenways Plan, which the MPO’s policy committee approved at the end of 2016.

With the big-picture plan in hand, the MPO raised $500,000 from public and private sources to hire a pair of engineering firms to conduct field research, estimate budgets and figure out all the other nitty-gritty details that those 80-some projects would require.

The first company, ISG Engineering and Architecture in Des Moines, packed up its gear and mapped out 145 sites throughout the region. The second company, Denver-based McLaughlin Whitewater Design Group, with local subcontractors RDG Planning and Design and the Des Moines office of engineering giant HDR, focused on downtown and proposed a different solution for each of the three low-rise dams. The area around the current Center Street dam would become “a high-energy adventure,” the Scott Street dam would provide “a nature connection,” and the Fleur Drive dam would invite people to “learn and play,” according to the official Water Trails Engineering Study.

The bad news: Water trails aren’t cheap. The $117 million cost would include about $56.5 million for the Center Street dam; $21.5 million for the Scott Street dam; and $28.1 million for the Fleur Drive dam. Those price tags include the cost of riverside amenities. Regional projects outside of downtown would cost about $11 million.

The good news: It isn’t an all-or-nothing deal. If Johnston wants to install access ramps and rinse stations on Beaver Creek, it can go right ahead. Pleasant Hill officials can build picnic shelters along the Des Moines River whenever they’re ready. The downtown projects could start within a year or two if the funding comes together.

Advocates for water trails often compare them to the ribbons of asphalt trails that started unspooling through the metro area 20 or 30 years ago.

Water trails could become popular in the same way, and they have an advantage: The water is already there.