Above: “A Monumental Journey,” envisioned here, will be built from 25 tons of shiny black bricks. The sculpture’s hourglass form reflects a West African “talking drum.”

Writer: Michael Morain

For years, a small stone marker in a local church parking lot was the only landmark that honored the dozen African-American lawyers who gathered in Des Moines in 1925 to establish the National Bar Association. The organization was founded as an alternative to the almost exclusively white American Bar Association, which had admitted only one African-American member by 1911.

But a new reminder of that historic turning point will be hard to miss. It’s built from 25 tons of shiny black bricks, stands 30 feet tall and, like the group it honors, presents itself as “an immovable object,” says the sculptor, Kerry James Marshall, over the phone from his home in Chicago. “It’s a force to be reckoned with.”

An installation crew has spent the last few months preparing “A Monumental Journey” for its public dedication on July 12 at the pocket park on the northeast corner of Second and Grand avenues, where more than 8,000 cars pass every day, according to traffic officials.

Making ‘the Invisible Visible’

The sculpture’s form was inspired by traditional African drums and is designed to make “the invisible visible,” Broderick Johnson, a former assistant to the country’s first black president, said at the groundbreaking ceremony in November 2016. Even while other cities are figuring out what to do with their Confederate monuments, Johnson says the new sculpture in Des Moines celebrates “that sense of optimism, that sense of turning the improbable into the probable, and the belief that all of our children have the right to a bright future.”

But for more than a decade, the sculpture’s own future wasn’t so bright. The artwork itself is the result of a monumental journey.

In 2006, National Bar Association member and Polk County District Judge Odell McGhee proposed the monument idea to the Greater Des Moines Public Art Foundation. He and other NBA members wanted to honor their group’s 12 illustrious founders—two from Kansas City, five from Chicago and five from Des Moines.

With the NBA’s support, the public art foundation led the slow-but-steady efforts to find the location, the funding and the artist.

The search for a suitable location took several years because at least two proposed sites, up the hill by the Iowa Supreme Court building or down by the riverside federal courthouse, were tangled in red tape and logistical quandaries. Major downtown projects by the river involve the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Fundraising was stalled for a while, too, but the project’s champions eventually raised more than $1.2 million from more than 200 donors.

Perfect Fit

The search for an artist was much easier. Des Moines Art Center Director Jeff Fleming contacted Marshall, whose work he had admired for many years. The artist, now 62, had won a MacArthur “genius” grant in 1997 and has exhibited artwork about African-Americans and the Civil Rights movement in museums around the world. His solo exhibition last year at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York—the museum’s largest show devoted to a living artist—was “neither a political protest nor an appeal for progress in race relations,” according to a glowing review in The New Yorker. “It’s a ratification of advances already made.”

“I thought he’d be perfect,” Fleming says. “The final work is going to be extraordinary—groundbreaking—and significant on an international level.”

Years ago, when Marshall visited the University of Iowa as a guest artist, he saw a campus that looked different from his neighborhood in Chicago or the one in south Los Angeles where he grew up. He laughs over the phone: “I swear I’d never seen so many white people in my life.”

So when he learned that some Iowans are, in fact, black—and that some black lawyers made history in Des Moines, of all places—he was intrigued.

“I’m always up for a challenge,” Marshall says.

One of his initial concepts called for a giant seesaw, like the scales of justice, which visitors could have tipped one way or another.

But he abandoned that in favor of an hourglass form, like a West African “talking drum”—so named for its ability to mimic both the tones and rhythms of human speech. The drums are a centerpiece of the Yoruba people, whose drummers historically used them to relay complex messages over great distances both in Africa and in the United States, where some slaveholders prohibited them.

Marshall decided to cut his sculptural drum across the middle, at its waist, and push the upper half off-kilter. When the project’s engineers told him he could push it even farther, almost to the tipping point, “he loved the idea,” according to Greater Des Moines Public Art Foundation Director Jessica Rowe.

“It emphasizes the graceful or perhaps precarious way that our justice system works,” she says. “It strives for balance but it’s not perfect.”

The drum’s minimalist form also appeals to Marshall because it nods to African art without borrowing the bright colors or busy patterns of folk art. Instead, the sleek sculpture’s manganese black bricks seem to suit the site’s urban setting in the 21st century.

Marshall says he wanted to “pull something out of the past and push it into the future.” It’s a goal he shares with the National Bar Association’s founders, whose names are engraved around the base.

“If somebody doesn’t let you in, you can cry about it,” he says, “or you can make your own group and go about your business, which is exactly what they did.”

he wanted to “pull something out of the past and push it into the future.”

Photo by Cameron Wittig; courtesy Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

The Dedication

Sculptor Kerry James Marshall plans to attend a public ceremony to dedicate “A Monumental Journey” at 11 a.m. July 12, at the northeast corner of Second and Grand avenues. Later that day, he’ll discuss the project during a free lecture at 6 p.m. at Sheslow Auditorium. For details, visit dsmpublicartfoundation.org.

The National Bar Association

“A Monumental Journey” honors the 12 black lawyers who founded the National Bar Association in Des Moines in 1925, at a time when many Iowa workplaces, eateries and restrooms were segregated and lynchings were still common in parts of the United States.

Today, the NBA’s 60,000 members work to promote civil rights, justice reform, economic equity, diversity on the federal bench, and other causes across the country and here in Iowa, where blacks are imprisoned at 11 times the rate of whites, according to a 2017 study by the nonprofit Sentencing Project in Washington, D.C. That’s the third-worst ranking in the country.

It’s worth noting some of the remarkable achievements of the five NBA founders who lived in Des Moines.

S. Joe Brown (1875-1950) was the founding president of the Des Moines chapter of the NAACP and the first African-American lawyer to appear before the Iowa Supreme Court. He defended 30 clients who faced the death penalty; none were executed, and 10 were acquitted.

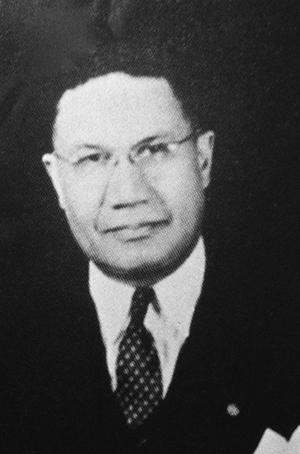

Charles Howard Sr. (1890-1965) was a first-year law student at Drake University when he passed the bar exam and successfully defended a client charged with first-degree murder. Over his career, he saved more than 75 people from execution.

James Morris (1890-1977) opened a law practice after serving in World War I and briefly worked as a deputy Polk County treasurer. He bought The Iowa Bystander newspaper in 1922 and served as its editor and publisher until 1972.

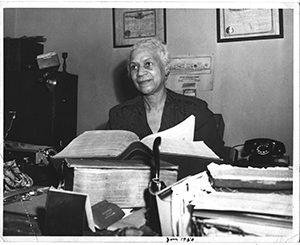

Gertrude Durden Rush (1880-1962) was the second woman to practice law in Iowa, after Arabella Babb Mansfield of Mount Pleasant became the first female lawyer in the United States. Rush founded a number of nonprofits, including the Protection Home for Negro Girls, and was a prolific playwright and composer. She published the hymn “Jesus Loves the Little Children” in 1907.

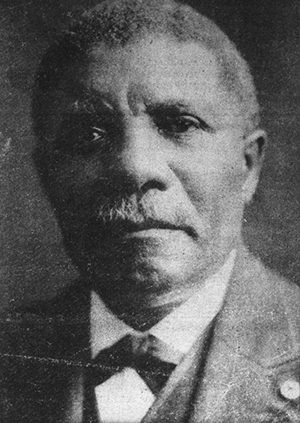

George Woodson (1865-1933) was born to enslaved parents in Virginia, earned a law degree from Howard University in 1895, and opened a law practice in Iowa a year later. He was one of the founders of the 1905 Niagara Movement, a forerunner of the NAACP.

Source: The Iowa Lawyer, the official magazine of the Iowa State Bar Association.