Above: Known for her large colorful tapestries, Jamaica-born Ebony Patterson often explores questions of identity, gender norms and the human body. The Art Center will debut “…among the blades between the flowers…,” a favorite of both co-curator Mitchell Squire and Art Center Director Jeff Fleming, in the upcoming exhibit, called “Black Stories.”

Ebony G. Patterson (born 1981), “…among the blades between the flowers…” (2018) detail; hand-cut jacquard-woven photo tapestry with glitter, applique, beads, trim, brooches, feathered butterflies, fabric, silk flowers, and hand-embellished owl on shelf, on artist-designed fabric wallpaper; 10.8 x 14.6 feet. Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections. Photographer: RCH Photography, courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

(Editor’s Note: This story was included in the list of our favorite 2020 print stories. For reference, it was published in September 2020.)

Writer: Christine Riccelli

Every picture tells a story, but so does every person who sees that picture.

And it’s those stories that the Des Moines Art Center hopes to showcase as much as the artwork on display during the exhibit “Black Stories,” which opened over the weekend.

Drawn from the Art Center’s permanent collections, the exhibit features a compelling mix of works—paintings, photos, mixed-media pieces, sculptures, drawings, artifacts—by a wide range of international, national and regional Black artists, including such well-known names as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kerry James Marshall, noted up-and-comers like Jamaica-born Ebony Patterson, and acclaimed Central Iowa-based artists Jordan Weber and Mitchell Squire.

The exhibit promises to be a “celebration of blackness and about turning a predominantly white space into a space where black people, brown people and indigenous people can feel comfortable,” says Weber, a co-curator of the exhibit along with Squire.

Indeed, the driving motivation for the show is the Art Center’s desire to form a deeper and more vibrant connection with the local Black community. From the time the exhibit was conceived more than a year ago, Art Center Director Jeff Fleming says his goal has been to “listen, make sure we were involving the Black community in what we’re doing, and provide an opportunity where there could be partnership and collaboration.”

To that end, Fleming decided to stay out of the decision-making process and invite Weber and Squire to co-curate the show. “They are both incredibly knowledgeable and have come up with some extraordinary ideas,” he says.

Planning for the exhibit began before George Floyd was killed, before the Black Lives Matter movement reemerged, and before many in the white community were jolted out of complacency about systemic racism and the need to end it. While the vision for the exhibit has remained the same, it’s now more relevant, necessary and urgent, those involved with the project agree.

“We would seem tone deaf if we didn’t address what’s been happening in 2020,” Squire says. “The things that have happened—COVID-19, the economy tanking—have affected Black people disproportionately. It would be hard to have a show and ignore that.”

The exhibit “is needed now more than ever so we can have these spaces to celebrate ourselves,” Weber adds. “The vision has become magnified.”

To help bring that vision to life, an advisory committee of 15 local Black leaders and artists was formed to provide “advice, support, participation and guidance,” Fleming says. (See list of members, below this story.)

“The local Black community is very diverse in and of itself,” says committee member Mary Chapman, vice president emeritus of Des Moines Area Community College.

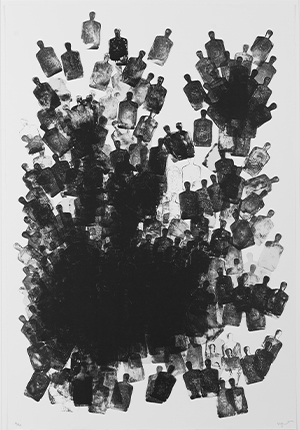

This lithograph by Mitchell Squire depicts miniature silhouettes of the black torso figure used on law enforcement training targets. “From afar, the … lithograph seems to depict a collection of elegant translucent perfume bottles,” the Minneapolis Institute of Art wrote of the work. “Upon closer inspection, the black silhouettes reveal themselves as law enforcement targets … in an arbitrary pile suggestive of a mass grave, the bodies too numerous to count.”

Mitchell Squire (born 1958), “Gladiators” (2013); lithograph on paper, printed from two aluminum plates; 43 1/2 x 28 5/8 inches. Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections. Photographer: Rich Sanders.

“The purpose of the committee is to be intentional in reaching out to these various Black communities not only to [draw] them into the Art Center but to make them feel welcome there. As they share their perspectives and stories, the artworks become activated … and the experience becomes interactive.

“Storytelling is such an art in the Black community,” Chapman adds. “Hopefully the art will inspire personal stories of [visitors’] own memories and experiences.”

A major part of the project involves capturing those personal stories through a variety of means and platforms, such as one-on-one conversations, social media, online forms, interviews, and pencils and paper in the galleries that visitors can use.

The advisory committee will then select stories to appear in a book the Art Center will publish, which will serve as the show’s documentation. “Temporary exhibits come and go and can be quickly forgotten,” Fleming says. “This allows the project to have an extended life, to have a permanence.”

In addition to the book, an array of public programs will accompany the exhibit, all planned by the committee and co-curators. At press time, the committee was brainstorming ideas that could work if the pandemic continued through the exhibit’s run. “We’re trying to figure out what the engagement could look like,” Chapman says. “We want to frame whatever we do in ways that will help keep the conversation going.”

“It’s our strongest desire to have public activities,” Fleming adds. “We just won’t know the specifics until we’re closer to the opening as we’ll need to figure out what is appropriate and safe.

“But it is certainly our hope that we can have these opportunities to engage with one another on a human level.”

Wangechi Mutu is an internationally renowned Kenyan artist whose work has been exhibited worldwide. “Water Woman” is a sculpture of a “nguva,” an aquatic being of East African folklore that’s part human and part “dugong,” a relative of the manatee. In contrast to Western depictions of women with pale skin and light hair, the “Water Woman” siren is “represented by the luminous, charcoal-colored female body, which is a vein of inquiry central to Mutu’s work,” according to the Art Center.

Wangechi Mutu (born 1972), “Water Woman” (2017); bronze; 36 x 65 x 70 inches. Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections.

Sharing Stories

Artworks explore the trials and triumphs of the Black experience.

For “Black Stories,” Des Moines Art Center Director Jeff Fleming gave artists Mitchell Squire and Jordan Weber access to the museum’s entire collection by Black artists and the freedom to decide which works to include and how to exhibit them.

“My intent was to listen to their ideas and not dictate anything in any way,” Fleming says, adding that the co-curators chose “wonderful, potent, powerful works that speak to our moment in time.”

To make the selections, Squire came up with an approach that divides the works into four categories, which, he says, “seemed to coalesce in ways stories of the Black [experience] might be told.”

Such organization “is more or less the way I tend to work,” adds Squire, a mixed-media, installation and performance artist who has had solo exhibitions throughout the country and in London. He’s also a professor of architecture at Iowa State University. “I tend to create an initial structure to the array of things I’m considering.”

Within this framework, the pieces within each grouping will be intermingled when they’re installed, displayed in ways that invite conversation and interaction.

Specifically, the four groups of works include the following:

“In Black and White” consists of works that “tell stories that might be told in black and white; they pull no punches,” Squire explains. “There are a number of artists whose aesthetic is about blackness and telling the story in stark reality.”

For example, Squire’s evocative lithograph “Gladiators” depicts miniature silhouettes of the black torso figure used on law enforcement training targets (see image farther up in this story).

Nick Cave is a sculptor, dancer and performance artist who often utilizes found objects in his works. For his “Rescue” series, he connects rescuing pets and reclaiming discarded objects. “Dogs are associated with loyalty, commitment and protection,” noted the Denver Art Museum. “The inclusion of furniture and an elaborately adorned metal structure accentuate the dreamlike aura that Cave likes to evoke in his work. The dog becomes the benevolent guardian of this self-contained forbidden world.”

Nick Cave (born 1959), “Rescue” (2013); mixed media with ceramic birds, metal flowers, ceramic Doberman, vintage settee and light fixture; 88 x 72 x 44 inches. Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections.

Another group, “In Living Color,” focuses on stories and a vision told through “a vibrant expression of color,” Squire says, pointing to Ebony Patterson’s work, which is titled “… among the blades between the flowers,” as his favorite of this group. A recent Art Center purchase, the stunning woven tapestry (see image at the top of this story) will be on display for the first time during the exhibit.

“I hope it stands for a promise among those blades and between those flowers,” Squire says, specifically a “promise of a commitment by the Art Center to acquire works by younger Black artists.”

He believes that often, “the more recent the work, the more it resonates with the public, especially the younger public.” He adds that he especially hopes “there can be more acquisitions of Black portraiture, which is on the rise. … Viewers may have the knowledge of art history to fully appreciate abstraction, but when you stand in front of a portrait it resonates with you immediately. It can be like looking at a mirror.”

The third group, “In Wakanda,” consists of works that are largely material-based, including sculptures and mixed-media pieces created with found objects. Squire summarizes it as “a material reclamation of the past to move forward. … There is a great versatility and variety of works, and they’re all different aesthetically. But they’re all primarily interested in a future crafted out of the past.”

For example, co-curator Weber’s mixed-media work in the “Wakanda” section, a part of his “Chapels” series, contains earth and marble from the site of the Charleston, South Carolina, church where nine African Americans were massacred in 2015 (see below).

Over the past decade, artist and activist Jordan Weber has focused on social justice issues, historical and current events, and identity in a compelling range of sculptures, mixed-media works, and site-specific installations that have been exhibited across the country. One of his most well-known works is a partially deconstructed police car with plants growing out of the back seat, created in response to the 2015 police shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. His “Chapels” series uses materials from sites of historical significance, such as this one from Emanuel African Church, where a white supremist killed nine African Americans during a Bible study in 2015.

Jordan Weber (born 1984), “Chapels” (series) (2017); marble, earth (Charleston, South Carolina, Emanuel African Church shooting), wood, plastic packaging and resin; 24 x 24 x 4 1/4 inches. Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections.

In his sculptures, paintings and installations, Weber often works on sites of significance—Malcom X’s birth home in Omaha, for example—or uses materials that have historic meaning. His interest in the historic and spiritual importance of objects is driving his curatorial focus for the unnamed fourth component of the exhibit, which will include traditional African artifacts such as furnishings, masks, spears, doors and other items.

“A lot of these artifacts have spiritual histories,” Weber says, adding that many of them will be displayed in a separate, chapel-like room with seating. “We want to provide a space where you can really experience your ancestry or West African beginnings and origins. We want people to be fully immersed in the historical aspect of being African American.

“I think it’s really important right now to delve back into blackness without feeling like … we’re being seen as a threat,” he adds. “It will be a great experience to be among a lot of Black and brown people in Des Moines and be surrounded by our elders and ancestors.”

No matter which artworks resonate the most with visitors, Squire hopes that everyone walks away from the exhibit having a better understanding of the “importance of Black artists telling their stories and that they will tell their stories in good times and bad,” he says. “They always manage to carve out a fresh expression of and for themselves. I think that that fact is an amazing story in and of itself, and provides a singular hope for the future.”

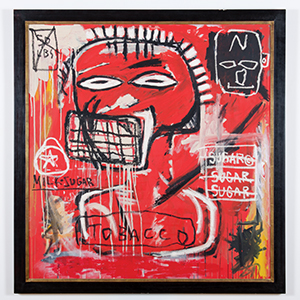

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) first gained notice as a graffiti artist in Manhattan. Within a few years, he gained worldwide acclaim for his neo-expressionist paintings and mixed-media works, which fuse elements such as poetry, historical information, abstraction, figurative images, and contemporary critique. He died of a heroin overdose at age 27. In 2017, a Japanese billionaire bought a 1982 Basquiat painting for $110.5 million.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988); “Untitled” (1984); acrylic and oil stick on canvas; 42 x 40 inches. Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections.

Advisory Committee Members of “Black Stories”

Vickee Adams

Dwana Bradley

Ray Brown

Teree Caldwell-Johnson

Linda Carter-Lewis

Mary Chapman

Angela Jackson

Bo James

Izaah Knox

Mary Madison

Jerrica Marshal

Robert Moore

Negus Rudison-Imhotep

Mitchell Squire

Jordan Weber