Written by Mary Challender

Photos by INEZ

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]ands on hips, Alejandra Villanueva stares down the camera. Her shirt is rolled up at the bottom, exposing the message written on her bare belly in bold black letters: 16 and not pregnant.

Out of all the stereotypes about Latina teens, the one of inevitable teen motherhood was the one that had always most frustrated the North High School junior.

She wanted to tell people that her future was going to be different—that she loved singing, for instance, and acting—but she was too shy and nervous. Like many students, she spent most of her time at school hiding in the margins, unremarkable even in her own eyes. “I just saw myself as that one Mexican girl at school,” Alejandra admits.

She credits a class called Urban Leadership 101 and the two teachers behind it, Kristopher Rollins and Emily Lang, with reawakening the potential she once felt was inside her. The class, held at Central Campus and open to all Des Moines high school students, studies social movements and deconstructs how leaders emerge within them. The goal is to motivate students to become activists in their communities. On a classroom billboard, photographs of students in the class are interspersed with photos of famous leaders, such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Bayard Ruston. The message: Your voice can be just as important as long as you’re brave enough and willing enough to take that step.

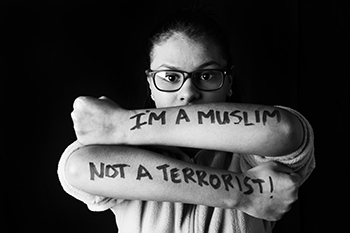

This past school year, while studying various groups oppressed by war, students were captivated by a photo project featuring Syrian refugees who used messages written on their bodies to communicate how their lives had been uprooted. In collaboration with Des Moines photographers Joe Crimmings and Jami Graves, who operate under the company name INEZ, the students decided to tackle a similar project to address stereotypes about themselves and youths in general.

Students were asked to write a short sentence that would help create a dialogue about prejudice. Lang says she was impressed by the thought and honesty that went into the messages the students chose to be photographed wearing. “Some of them took some big risks to expose themselves,” she says. (Some of the photos are featured in this story.)

Making Connections

Rollins, 32, and Lang, 31, met when both were hired at Harding Middle School in 2010: Rollins to teach global studies and literacy, Lang to teach drama. “I saw amazing potential in Emily and Kristopher,” says Des Moines School Superintendent Thomas Ahart, who was then Harding’s principal.

At the time, Ahart was leading a massive effort to improve student achievement at the struggling school. “We knew there was a large segment of our student body that we really didn’t have fully engaged in school,” he says. “They were great kids; we just hadn’t figured out how to connect with them.”

With Ahart’s backing, Lang and Rollins, who later married, began working together on ways to draw in those students. They started with Share the Mic: Community Voices Creating Change, which gave students a regular venue for performing works they or others had written while raising money for a charity they chose.

Next came Minorities on the Move, a two-week summer workshop, which began as an invitation-only program aimed at Harding’s student leaders and now is working to develop the next generation of educators.

As an alternative to traditional literacy programs, Lang and Rollins created Hip-Hop: Rhetoric & Rhyme, a popular elective that seeks to teach Harding students the rhythm and rhyme of effective writing through song lyrics while also investigating hip-hop as a social movement.

Finally, inspired by the annual Brave New Voices youth poetry slam festival, Rollins and Lang launched Movement 515, a weekly after-school program that allows students across the Des Moines area to hone their skills in spoken word performance and graffiti art.

Tupac: Today’s Shakespeare?

At the heart of all four programs is Rollins and Lang’s belief that just because a student may not be a master of the forms traditionally used to measure achievement, it doesn’t mean he or she isn’t literate.

“A spoken word poem is not considered as literate as a five-paragraph essay,” Rollins says. “We’re challenging that a little bit. We’re trying to put Tupac up there with Shakespeare. Some of the role models our students look up to, we’re trying to legitimize them. Who’s to say Queen Latifah is not as valuable as Yeats?”

This past school year, Rollins and Lang added their first offering for high school students with the Urban Leadership 101 class. Alejandra says she likes that the class deals with issues that are relevant to her life. But if she feels braver now—willing, even eager, to step into the spotlight, as she did during the photo shoot—she says it’s not because she’s inspired by the daring of leaders of the past but because Rollins and Lang work hard to create a learning environment where students feel safe taking risks.

“I’m trying to put this in words,” Alejandra began. “I’m happy to be there every day, and when I leave, it’s like I have to do everything on my own and I don’t have help anymore.”

Blurring the Line

Rollins and Lang say they deliberately blur the line between teacher and student in their classes, freely sharing their own thoughts and opinions before asking students to venture the same. They allow students to speak about what’s going on in their lives and communities, in their own voices, even if the words might sometimes be a little rough or the subjects generally considered not appropriate for the classroom.

“We know we come from very different backgrounds,” Lang says. “We grew up white and middle-class and we say, ‘We’re not going to insult you by saying we have the solutions to what’s going on in your lives but we’ll give you a place to talk about it.’ ”

They also hold students accountable. Butts in seats, they admonish students with poor attendance in other classes. Just because you don’t feel accepted in a classroom doesn’t mean you can use that as an excuse to quit learning.

Mario Cruz, 16, who will be a senior this fall at Hoover High School, says Rollins and Lang pour so much energy into the leadership class that he’s able to feed off it for an entire school day. They’ve even inspired him to start writing again, he says, and made him feel “safe enough and brave enough” to perform his work. (See photo, above.)

“It seems they brought out the leadership that was still hiding within me,” Mario says.

Program’s Growth

Today, an umbrella organization called RunDSM (a name inspired by the iconic hip-hop trio Run-DMC) unifies the five programs Rollins and Lang spearheaded. RunDSM is continuing to grow. Teachers have been hired for the upcoming school year to serve as RunDSM coordinators at all five Des Moines high schools and to lead Movement 515 spoken word and street art workshops.

A 102-level Urban Leadership class is also slated to be offered in the new school year. And Urban Leadership 101 students helped teach at the Minorities on the Move workshop in June, with the hope that it will inspire them to want to become educators themselves.

Davonte Binion, 15, who participated in RunDSM programs while in middle school at Harding, is looking forward to taking Urban Leadership 102 in the fall after taking Urban Leadership 101 as a freshman. He says his interaction with Rollins and Lang in the RunDSM programs has not only given him the courage to envision a future as a professional poet and photographer; it’s given him the strength to hold on to that vision when others doubt it.

“A lot of people down poetry, and they say you can’t make a life of it, but I want to make this a career,” says Davonte, a student at North High School. “The same with photography. They say, ‘You don’t even know the skills.’ But I’m going to learn them.”

Like Alejandra, Davonte says it didn’t take him long to settle on the message he wanted for his photo: “Be what they say you couldn’t” (see photo, right). “People are always telling you, ‘This is how your life is going to be,’ ” he says. Now, he says, he’s not afraid to respond, “I don’t want it to be that.”

“It’s an ‘I’m going to be who I want to be’ kind of thing,’ ” he says.