Written by Barbara Dietrich Boose

Photos by Duane Tinkey

Mary LaHay

Iowa Friends of Companion Animals

Mary LaHay didn’t grow up as an animal lover. Nor had she ever heard the words “puppy mill.” All that changed because of two key events: Her significant other made it clear their prospective marriage was contingent upon their getting a dog; later, they responded to an ad for a puppy in Altoona.

“This dirty man led us to an outbuilding, and you could hear a cacophony of dogs barking. The place was filthy and reeked of dog urine,” LaHay recalls. “I literally had to leave because I was getting nauseated.” The man told them to go outside and he’d bring out some puppies.

“I couldn’t bring myself to touch them. They were covered and matted with dried urine and stunk so bad,” she says. When her husband went to retrieve a puppy that had wandered around the building, she says, “he saw the stacked cages, just loaded with dogs, going crazy.”

The second key event was when the couple acquired their first dog, a Corgi-rat terrier mix, Ruby, from a backyard breeder. LaHay “fell head over heels in love” and had to get another dog. Some online research kept her up one night. At the time, in 2008, Iowa had more than 450 commercial dog breeders who were licensed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, nearly 60 percent of whom had been cited for significant violations to the federal Animal Welfare Act (AWA). Many housed hundreds of adult breeding dogs. Although the number of USDA-licensed breeders in Iowa currently stands at 222, the state still ranks second in the nation for number of puppy mills, with more than 15,000 adult dogs. In 2013, 41 percent of those facilities were cited for AWA violations.

That drove LaHay in 2009 to form Iowa Friends of Companion Animals, a 501(c)(3) organization that seeks to raise awareness and share information about the welfare of companion animals. Its sister organization, Iowa Voters for Companion Animals, is a 501(c)(4) that lobbies for legislative change and increased regulatory oversight. She uses the Utah-based Best Friends Animal Society’s definition to define puppy mills as “facilities that keep so many dogs that the needs of the dogs and puppies are not met sufficiently to provide a reasonably decent quality of life for all the animals.”

LaHay makes clear she is not opposed to all dog breeders. “There are a lot of good breeders out there,” she states. Rather, she wants to expose those who cram dogs into stacked wire cages barely bigger than they are, kept in windowless sheds and susceptible to filth, sores, parasites, diseases and other hellish fur-matting miseries.

“I really thought that when I found out those realities, I’d be able to spend maybe a year working on this and then be done with it,” says LaHay, who in 2011 quit a lucrative job as a territory sales representative for a medical device company to run Iowa Friends full time. “I had no idea I’d run into such opposition.”

No surprise that opposition has come from the breeders themselves. Recent data show that puppy mills generate $17 million annually. The industry has a lobbyist at the Iowa Legislature; a single large breeder in Lee County has his own lobbyist. Other big opponents of increased state legislation include the American Kennel Club and entities that oppose any restrictions relating to the state’s agricultural industry.

Iowa Friends’ cause is focused on protecting pet-animal welfare, however, not that of livestock. The state should look at Illinois, LaHay says, a fellow agricultural giant that is ranked the nation’s best in terms of animal welfare.

“Farmers have a vested interest in making sure their livestock are healthy,” she says. “But in Iowa, that’s not true for these dogs. Unlike cattle and hogs, these dogs are so replaceable and so disposable. A sick, injured, abused dog still gives birth to cute, fluffy puppies, and they are the product. And even if those puppies aren’t healthy, the puppy mill is still able to sell them, because very often that ill health doesn’t show until after they’re sold.”

That’s why the marketplace can’t be counted on to drive bad breeders out of business, and why the issue is also one of consumer protection, she points out. “Most of the people who learn their sick puppy came from a puppy mill feel shame when they realize they contributed to the industry,” she says.

To avoid that, LaHay says before buying a puppy, people should insist on seeing both its mother and where the mother lives. She also encourages people to visit Iowa Friends’ website (wp.iafriends.org), which offers extensive information, photos and videos about puppy mills. Most important, she wants citizens to contact their legislators to support increased state oversight of USDA-licensed dog breeders.

Under current law, the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship can but is not required to inspect federally licensed breeders if it receives a complaint. Iowa Friends wants that to be a requirement. Of the top four dog-breeding states in terms of numbers, Iowa is the only state that doesn’t have that. “If we can have that state oversight, then we can increase the standards because we can police them,” LaHay says.

The standards Iowa Friends is pushing include increasing cage size from six inches longer than its inhabitant to 12 inches; requiring cages to have adequate solid flooring instead of paw-punishing wire; ensuring dogs have access to the outdoors; and requiring each dog to be checked annually by a veterinarian.

Iowa Sen. Matt McCoy, a Democrat who represents the south and southwest portions of Des Moines, says LaHay’s style makes her more effective than organizations viewed as extreme by agricultural interests. He’s introduced legislation, eligible for Senate debate in the 2015 session, supporting Iowa Friends’ goals.

“She’s been a breath of fresh air at the Capitol,” he says of LaHay’s issue-focused, fact-based approach. “She’s an enormously passionate person with a great desire to serve the greater good and protect these animals. And this is not a Republican-Democrat issue; Republicans love their dogs as much as Democrats do. It’s a humane issue.”LaHay’s ultimate goal is for Iowa Friends “to be put out of business.” But until inhumane puppy mills disappear, she says with quiet intensity, “that’s not an option.”

“I’d give anything for this to not be true, for this not to be the big problem that it is,” she adds. “But as long as it is, I will tell anyone who will listen.”

Moses Bomett

Hopeful Africa Inc.

In his talk at TEDxYouth in Des Moines in October 2013, Moses Bomett shared an anecdote about John, an African mosquito net salesman whose product is a critical yet affordable way for people to fend off malaria. His business employed 10, who in turn supported additional family members – 60 to 70 people in total. But when the United Nations swooped in with a donation of 250,000 mosquito nets, it put John out of business. A few years down the road, when people needed to replace their nets, John no longer sold them, and the United Nations had moved on.

“Simply giving donations will not solve the problems in Africa,” the 22-year-old Bomett says. “Working in partnership with local people and organizations is what is needed for long-term solutions, and education is key to those solutions.”

His empowering teach-a-man-to-fish philosophy is at the heart of his nonprofit organization, Hopeful Africa Inc. Since it began in 2008, it has raised more than $40,000 to pay for textbooks, tuition, teachers and even trees and a water catchment system at seven schools in Kenya, Bomett’s home country, all toward the goal of improving educational quality and opportunity.

Bomett’s school experiences, in fact, planted the seeds for Hopeful Africa. He spent most of his first 14 years in Kenya, moving to West Des Moines with his family when his parents decided to seek post-high school educational opportunities in Iowa for Bomett’s three older siblings. Although Bomett had attended a top-ranked boarding school in Kenya, he was struck by Valley High School’s opportunities.

“Our catalog of classes was this thick book. We had all these choices – athletics, arts, music, drama, clubs, activities,” he says. “Why is it not the same back in Kenya? What are we doing wrong? What can I do? All these questions kept rolling around in my head.”

In 2008, a teacher encouraged him to talk about those issues in an Iowa High School Speech Association competition. Although he jokingly claims that he “froze up and lost 50 percent of my words,” the judges liked his topic enough to advance him to the state competition. After he gave his speech at the University of Northern Iowa, he thought “that was it” – until a friend challenged him to come up with solutions to the problems he had described. They created the Hope 4 Africa Club at Valley.

“I looked back to my roots in Kenya, the communities that I grew up in and ways we could help some of the schools there,” Bomett says. “We started with some simple things – selling baked goods, selling T-shirts, organizing basketball tournaments – to raise money to help improve education.”

Bomett’s commitment and vision have driven the organization’s growth since then. “You can see this is his passion, and it’s infectious,” says Cheryl Stouffer. When Bomett’s mother and father returned to Kenya, Stouffer and her husband, Bob, became Bomett’s Central Iowa “parents.”

After graduating from Valley and enrolling at Iowa State University with a triple major in economics, political science and international studies, Bomett started a Hope 4 Africa Club there and, with other volunteers, clubs at Waukee High School, the University of Iowa, the University of South Dakota, Loras College, the University of Minnesota and the University of Missouri.

The clubs and Hopeful Africa have brought textbooks, computers and electricity to classrooms in seven partner schools in Kenya. They have also supported the hiring of eight teachers, critical in a nation where, according to the World Bank, the student-teacher ratio is 47-to-1, compared with 13.5-to-1 in the United States.

“We value what the schools need and what they want to move forward. If it is water, we’ll help them with water. If it is electricity, we’ll help them with electricity,” Bomett says. “I can’t come into your house and say, ‘I think you need X, Y and Z.’ You’re the one who knows your needs.”

In September, the organization changed its name to Hopeful Africa and hired its first full-time employee in executive director and longtime “Hope Team” member Kyle Upchurch. The name change better reflects Africa’s progress and potential, Bomett says. “Some people said Hope 4 Africa implies the continent is hopeless,” he says. “It implies that we’re coming in with this Western savior spirit, which is not what we believe.”

Increasing fundraising efforts in a campaign called “Msingi” – “foundation” in Swahili – will be a priority for Bomett, Upchurch and other Hope Team members.

Financially, the organization presents a good case; according to its 2008-2013 impact assessment report, for every $1 it’s spent on operational costs, it’s spent $7 on programs in Kenya that have benefitted 1,800 students annually. Convincing Midwesterners to invest in Hopeful Africa’s work in a nation on the other side of the globe is no small task.

“In the Midwest, there are not many nonprofits that do Africa-related things,” Bomett says. “When I go to speak – say, at a high school in Ankeny – everyone knows nothing about Africa other than ‘Lion King’ or the images they’ve seen on TV. So it’s a wide-open opportunity. It’s an opportunity for people to do something bigger, to do something great.”

Now a student in Drake University’s Master of Public Administration program, Bomett intends to remain engaged with Hopeful Africa for the long haul. He has traveled to Kenya six times on behalf of the organization.

“I just love it,” he says. “It honestly does not feel like work whatsoever. And it’s amazing when you get to Kenya and see the people you’re helping and get to hear their stories. Our work has a ripple effect that you see among the students and the teachers.”

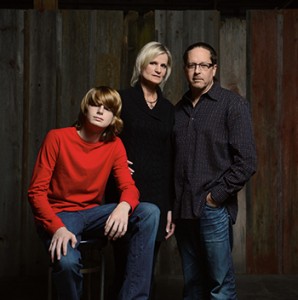

The Stevens Family

Joppa Outreach Inc.

Imagine this past winter: You’re homeless. It’s 5 below zero. You have too many possessions and perhaps a pet that preclude you from spending the night in a Des Moines shelter. If you’re lucky, you have a tent and a sleeping bag, but that won’t cut the dangerous cold. If you’re truly fortunate, you know Joe and Jacki Stevens and the volunteers of Joppa Outreach Inc.

The Stevenses were moved by their faith in the 1990s to deliver food and supplies out of their sport utility vehicle to Des Moines’ unsheltered population. In 2008, they gained an ulterior motive to do so: teaching their then-8-year-old son, Caleb, about volunteerism, entrepreneurship and leadership.

“There are two kinds of people in life – people who watch things happen and people who make things happen,” Joe says. “I wanted to show him that a few people can really make things happen.”

After spending up to 12 hours a day and thousands of dollars to help the city’s homeless, the Stevens family realized in 2008 they needed to establish a nonprofit organization to expand their efforts and give receipts for charitable contributions. They established Joppa Outreach, named for a community described in the biblical book of Acts that accepted all people regardless of their backgrounds. Caleb was appointed Joppa’s supplies manager.

“He was being asked for batteries and organizing feminine hygiene products before he was old enough to know what they were for,” Joe says. “It changed him right away. He wanted to spend his allowance on helping the homeless.”

Joppa’s timing coincided with the city’s move to ban propane tanks, used by the homeless to heat their shelters during Iowa’s bitter winters. After some fires in homeless camps were blamed on the use of propane, the Lutheran Church of Hope Cookie Ministries – which had expanded from distributing sweet treats to meals and propane – decided to opt out of the latter for liability reasons. Joe and Jacki stepped into the void.

“They are tireless workers for the homeless – raising money, organizing supplies, doing outreach, writing letters and going to meetings to advocate for the homeless,” says Diana Clay, a member of the Joppa board of directors.

Now taking up 1,900 square feet in a multipurpose building on the southeast edge of Des Moines’ East Village, Joppa reflects Joe’s background in for-profit efficiency and entrepreneurship. It features a calming intake area for homeless individuals to share their stories and discuss needs; a volunteer/student room; a dual warehouse-education area; a kitchen for weekly meal preparation; and a center where carts are loaded every Sunday with supplies and hot meals. The carts are color-coded for the various routes to homeless camps and “after-care” locations, where previously homeless individuals have obtained permanent housing.

“People have said we’re extremely organized. We want continuous process improvement, so our volunteers can focus their energies on interacting with the homeless,” Joe says.

That’s been the case for Aimee Smith, Joppa’s nutrition coordinator. She oversees three teams that pack coolers, prepare hot meals and collect food donated by Whole Foods Market and Trader Joe’s.

“The first time I went out [to the camps], I had really negative images of the homeless. My husband and I live and work downtown and had had some not-nice interactions with homeless people,” Smith says. “But I realized homelessness isn’t a choice for a lot of people. If they’re laid off from a job and miss a few mortgage payments, a few months later they’re living under a bridge. If you don’t have all your teeth or an address or a telephone, people don’t hire you.”

In addition to delivering meals, groceries and supplies ranging from toilet paper to tents, Joppa can give people a postal address and a prepaid phone. Its winter heat team provides propane heaters and tanks; a transportation team takes people to job interviews and medical appointments. Joppa advocates for the homeless, helps connect them to medical and social services, and – for those who obtain housing – helps with deposits and the first month’s rent. It also offers education programs for schools and youth organizations.

In all Joppa does with its approximately 300 volunteers, its goal is to address unmet needs among Polk County’s estimated 16,000-plus homeless people. Smith describes a chance meeting she and Joe had in a gas station parking lot, on break from that day’s outreach, with two homeless men Joe knew. Seeing the broken eyeglasses one wore, he arranged, on the spot, an appointment for the man to get new glasses.

“Joe has the ability to connect and speak with homeless people, which can be awkward for most people,” Smith says.

In 2013, Joppa’s approximate 500 volunteers delivered 4,799 meals and provided 394 health care assessments and 472 medical referrals. As of June 30 this year, Joppa had helped 162 individuals get off Polk County streets; 91 percent remain housed. The Stevenses also have ways of connecting with individuals and other organizations, many under the umbrella network Street Outreach Coalition, to maximize their impact and avoid duplication of services.

Joppa recently has become more structured. Jacki became its first full-time employee in May, as volunteer services director; Joppa also has a part-time communications coordinator and is seeking to hire an executive director. Joe, who maintains his full-time position as a digital analyst for a Des Moines branding firm, is working on formalizing its operations and fundraising efforts, including its Down and Out Homeless Fundraiser on Nov. 15. And he’s always looking for ways to improve.

“I’m not much for pats on the back. The need is big,” he says. “They say passion is love mixed with anger. We’re passionate and have a vision. We want this organization to be self-perpetuating after we’re long gone.”

Samantha Thomas

Global Arts Therapy

Near a Buddhist temple in rural Nepal in 2012, Samantha Thomas and her fellow volunteers were preparing an art lesson for children when a flatbed truck pulled up with their students. Fifty kids poured out, more than three times as many as Thomas had expected. Then it started to rain.

“The kids are all shouting, ‘Art! Art! Art!’ They were so excited,” Thomas recalls. That’s all she had to hear. She and her colleagues hustled the group into the temple and distributed art supplies and the split rice bags that were the students’ canvases. For the next three hours, “the kids were having the time of their lives,” she says.

That day illustrates how Thomas puts to work her passions for art, cross-cultural interactions and community service. She is the founder and director of Global Arts Therapy, which provides arts education programs and sustainable development opportunities to empower, educate and benefit disadvantaged youths and women in Nepal and Central Iowa.

The seeds for Global Arts Therapy were planted in her childhood on Des Moines’ east side. She attended numerous classes at the Des Moines Art Center, on scholarship, and listened to her parents openly discuss social issues and international affairs. “I was learning politics when I was 5,” she says.

Home-schooled, Thomas completed high school at age 16, moved out on her own, got a waitressing job and continued to make art. In her teens, she was among the first “emerging artists” selected for the Des Moines Arts Festival. After earning an international relations degree from Drake University in 2010, she taught art and English in South Korea. An opportunity during those two years to teach art for nine days in Nepal, through the organization Child Workers in Nepal, changed her life.

“I’m not thinking about inoculations or anything like that,” says the now 28-year-old Thomas. “I just loaded up a big suitcase of art supplies and said, ‘Let’s go do this!’ ”

“This” led to Thomas teaching women and youths in Kathmandu and rural villages to produce art from trash as well as sellable products such as salves, soap and candles. The experience affirmed her belief in the power of art and, after she returned to the United States, persuaded her to take a leap by establishing Global Arts Therapy. She’s worked to develop its programs in Central Iowa and Nepal and networked to promote them.

This past summer, she and two other Global Arts Therapy volunteers also taught a five-week art class to students at King’s College, a business school in Kathmandu.

The students produced art using recycled materials and designed a large installation piece for the college’s courtyard.

“I was much impressed with Sam’s ideas of engaging business students in art and painting in order to unleash their creativity, which leads to innovation – a key component of a successful businessperson and entrepreneur,” said Narottam Aryal, principal and executive director of King’s College, via e-mail. “Upon overwhelming interest and responses from our students, the college plans to continue working with Global Arts Therapy.”

In Des Moines, Thomas and her organization – which has received funding from the Community Foundation of Greater Des Moines and, in August, official status as a 501(c)(3) organization – have taught art classes at the Young Women’s Resource Center, the Iowa Homeless Youth Center and the Willkie House. This past summer, she taught students at a camp in Martin Luther King Jr. Park to make art using materials ranging from oil pastels to coffee filters.

“Sam clearly loved working with our students, and I was amazed by how she so calmly and patiently got 15-plus 6- to 10-year-olds to focus, participate and work respectfully with her supplies,” says Erin Todey, who oversaw the Martin Luther King Jr. Youth Program.

Discouraged and disenfranchised youths have a special place in Thomas’ heart.

“I’ve been there. I attempted suicide at 17 and ended up in the pediatric intensive care unit for nine days,” she says. “At age 17, you can feel like you’re never going to get out of a situation, that you’re stuck. Now I’m trying to be that driving force for other people who are at that point.”

Today, Thomas is “multitasking on steroids,” writing grant applications and planning more programs, fundraisers and trips back to Nepal. Youthful and tattooed, she is fearless about reaching out to business and community leaders and uncomplaining about the heavy lifting of nonprofit work.

“Paperwork is not an obstacle. Two hours and a headache and some alcoholic beverages afterward – that’s what paperwork is,” she says. “An obstacle is not having clean water or healthy food or electricity.”

Proudly displaying a colorful yarn bracelet knitted for her by a deaf Nepalese girl named Rita, Thomas notes, “This is why I get up every day to do this.”

“We have needs assessments and percentages and statistics, but our success is defined in the smiles and in the people we serve daily,” she adds. “If I see a kid who’s really into whatever art they’re doing or a woman in Nepal who says, ‘We’re using the pain salve you helped us make, and we have received relief from arthritis,’ we know we’ve done the right thing.”