Writer: Gunnar Olson

Photographer: Duane Tinkey

When Brad and Erin Gilbert bought their home on Henderson Avenue on Des Moines’ east side, they were excited about the 1920 bungalow—the front porch, hardwood floors and arched doorways, among other features.

“This one just had a homey feel to it,” Brad says.

“That – and the backyard,” Erin adds.

And for $70,000, the home carried a mortgage that was within their means, representing less than 12 percent of their $55,000 annual household income. It was, they believed, a great place to raise their firstborn son, Lucas, then 5 months old. They never imagined that the home would soon become a potential threat to their son’s health.

Brad and Erin, now 25 and 24, respectively, had met years earlier while working at the Pleasant Hill Hy-Vee, when he was a student at Southeast Polk High School and she at East High School. They moved South Carolina for his career, then returned to Iowa to raise their family.

The location of their new home was a convenient midpoint to their jobs, his at Wells Fargo & Co. in West Des Moines and hers at a day care in Pleasant Hill. But shortly after moving into the house in January 2014, the Gilberts started missing work to stay home and take care of Lucas, who was frequently sick with asthma-like symptoms.

At first, they didn’t make a connection between their new home and their son’s symptoms. They blamed day care, attributing his recurring bouts of illnesses to viruses being passed around among the children.

Then in April 2015, more than a year after moving in, the Gilberts took Lucas to the hospital with a high fever, a deep cough and troubled breathing. He had developed a bad case of pneumonia, requiring a weeklong stay in the hospital, with tubes to drain liquid from his lungs.

A chronic disease, asthma is the nation’s third leading cause of hospitalizations among children ages 15 and younger, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Iowa, asthma causes 60 deaths, 12,000 inpatient hospitalizations, 50,000 emergency room visits and 140,000 days of missed school annually, according to the Iowa Department of Public Health.

Such statistics are not an abstraction to the Gilberts; for them, the numbers represent their son. Unknown to them at the time Lucas was being hospitalized, a group of leaders in Greater Des Moines was laying the groundwork for a new program aimed at fighting pediatric asthma where it often starts: in the children’s homes. Called Healthy Homes East Bank, the program is on the forefront of a national movement in the medical profession to work hand in hand with officials from public health offices and other sectors to step out of the clinics and emergency rooms and treat chronic diseases where they often originate: in social and environmental settings.

Big Data

In 2009, Congress helped usher in the age of big data in health care with the passage of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act. The HITECH Act, as it’s called, pumped billions of federal dollars into the creation of a nationwide network of electronic health records.

Six years later, the nation’s hospitals and clinics sit on deep reservoirs of patient data. The question facing communities now is “How do we leverage this data to benefit not only the individual patient but also the population at large?”

This question was the premise behind the BUILD Health Challenge, a grant program established by a consortium of partners including The Advisory Board Co., the de Beaumont Foundation, the Colorado Health Foundation, The Kresge Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

“The power of data and the power of community, put together to solve our health problems—that’s what the BUILD Health Challenge is all about,” Brian Castrucci, chief program and strategy officer with the de Beaumont Foundation in Bethesda, Md., said in a phone interview.

Historically, treating illnesses has been separate from preventing disease and building a healthy community, Polk County Health Department Director Rick Kozin observes.

Sid Ramsey, vice president of business development for UnityPoint Health Des Moines, explains the problem: “The incentives have been misaligned for years. If you think about it, hospitals and physicians and clinics have been incentivized to treat illness.”

But hospitals are undergoing an awakening, he adds, in part due to the intent of the Affordable Care Act to reward medical providers for keeping people from getting sick in the first place to help contain rising health care costs.

“We’re all lifting our heads up and opening the blinders and looking at what people in the public health domain have been trying to tell us” about going beyond treating illnesses inside the hospital walls to addressing the underlying causes in the community, Ramsey says.

Public health experts call these underlying causes “social determinants of health.” While medical researchers know more than ever about the human genetic code, the humble ZIP code has become a reliable gauge of these social determinants. With a ZIP code, you can measure the age and condition of the homes in a neighborhood, average income levels, and the availability and quality of affordable housing, food, health care and social services. Greater Des Moines community leaders would soon learn just how useful this data could be for the 50316 ZIP code.

More Hospital Visits

The first time Lucas was in the hospital, Brad didn’t want people to take photos of his boy, stuck on the hospital bed with tubes in his body. Lucas should be at home, being his energetic self, doing what he loves, Brad says.

“He’s obsessed with baseball,” Brad says. “He will use anything as a baseball bat, even a fishing pole. Every night it’s ‘Play baseball, Daddy!’ ”

In June 2015, two months after his first hospitalization, Lucas returned to the hospital. He had trouble breathing and a bad cough. This time he was diagnosed with bronchitis, an inflammation of the mucus membrane. He was sent home with a nebulizer, a small machine with a breathing mask that administers medication in the form of mist into the lungs.

By now, the Gilberts had begun to suspect their home could be part of the problem, and Lucas’ bouts of sickness were taking a heavy toll. The Gilberts missed work to stay home with him, and with thousands of dollars in medical bills, they were unsure how much their insurance would cover.

“We just can’t get ahead,” Erin says. “We get something paid down, and something else comes up.”

“We talked about moving,” Brad says, “because the problems started when we moved here.”

The parents’ frustration is shared by Lucas’ pediatrician, Stacey Milani of Mercy East Pediatric Clinic in Pleasant Hill. She said the clinic sees many children with asthmatic symptoms, though some are easier to treat than others. She describes Lucas’ symptoms as more persistent and more challenging than most.

“He’s had a rougher course than many,” she says. “Sometimes you feel like you’re churning, because there’s only so much you can do to treat the symptoms unless there’s an underlying cause you can fix. As physicians, we don’t usually go into the home or into the environment.”

Lucas landed in the hospital for a third time in October 2015. It was pneumonia again. He had a high fever, trouble breathing and fluid in both lungs. Brad says Lucas saw an infectious disease doctor, who didn’t find anything.

For Brad and Erin, the three hospitalizations over six months were exhausting. “We didn’t really get answers,” Brad says. “Just ‘He’s sick.’ It was all a question mark.”

But help was on the way.

Healthy Home East Bank

The start of the Healthy Homes East Bank program can be traced to an unexpected conversation with a refugee mother.

Suzanne Mineck, president of the Mid-Iowa Health Foundation, a Des Moines-based grant-making foundation that strives to improve the health of vulnerable populations, recalls being with the young woman at a meeting. The attendees were talking about a recently established program to help refugees connect with primary care doctors, a key relationship for the refugees’ long-term health. Quiet most of the meeting, the young mother turned to Mineck and, with very little English, articulated the deeper issue that Mineck has been working years to address.

“She looked at me and said, first how grateful she was to help her family and other families like hers,” Mineck recalls. “But she said we all needed to understand that she could bring her son to the doctor every day, but if every night she took her son to a home with rodents and cockroaches and no heat, he would never be healthy.”

The young woman’s words were like “a punch in the stomach,” Mineck says. “It was as if someone had shown me a very clear picture of what social determinants of health look like.”

After the meeting with the refugee mother, Mineck called a meeting with Rick Kozin, director of the Polk County Health Department, and Eric Burmeister, executive director of the Polk County Housing Trust Fund. They raised the question: What should they do about this? The three of them committed to doing something, somehow.

Not long after, Kozin learned of the BUILD Health Challenge, which sought to partner with communities willing to move treatments “upstream,” beyond the clinic and hospital, to strengthen public health. Kozin, Mineck and Burmeister hatched the idea to treat pediatric asthma with home repairs. They decided to focus their efforts on a single ZIP code, so they could track progress and, they hoped, demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach.

They approached the region’s three major hospital groups—Broadlawns Medical Center, Mercy Medical Center-Des Moines and UnityPoint Health-Des Moines—and not only did all three sign on to the project as funders, Mineck says, but the hospital groups also agreed to use their patient data to test the hospitals’ assumption that children in poor neighborhoods are more prone to asthma. This degree of commitment from local medical leaders would prove to be pivotal.

Kozin, Mineck and Burmeister queried the data for cases of asthma, plotted the patients’ addresses on a map and isolated the highest concentrations of asthma down to the ZIP code level. The data confirmed that there was a higher prevalence of asthma in Greater Des Moines’ poorest ZIP codes, twice the rate of the state.

“I call it the ‘duh’ and the ‘aha,’ ” Minick says. “It’s obvious, but now we have the data and evidence to back it up.”

For their proposed pilot project, they narrowed the field further by focusing on the 50316 ZIP code, where they knew there was an active network of community champions working to revitalize the three Viva East Bank neighborhoods: Capitol Park, Martin Luther King Jr. Park and Capitol East.

They formed a consortium of 11 community partners, including the three major regional hospital groups, the Polk County Health Department, the Polk County Housing Trust Fund and the Housing Division of the Polk County Public Works Department. Their application to the BUILD Health Challenge was one of only seven nationwide to be awarded a $250,000 grant, in part on the strength of the hospitals’ active participation, and that grant was matched by $250,000 in local funds, plus in-kind donations of organizations’ staff time and existing programs.

The Gilberts happened to live in the neighborhood where this partnership would soon launch a potentially groundbreaking pilot program.

Home Assessment

The Gilberts learned of the Healthy Homes East Bank program last October, during Lucas’ third hospitalization. Expecting their second child, Erin and Brad agreed to participate, and not long after, nurse Carolyn Schaefer of the Polk County Health Department visited their home.

During the home health assessment, Schaefer observed likely asthma triggers, such as a gas range without ventilation to the outside, a bathroom with no ventilation, dog hair, and a roof that was beyond its useful life.

Then came surprising news to the Gilberts. “We were expecting them to come in and tell us what was wrong,” Brad says. “Not to fix it.”

But they were grateful to learn that the prescribed treatment for Lucas’ illness was, in fact, to make home repairs, including new vent fans in the kitchen and bathroom to reduce fumes and moisture, a new roof and gutters to reduce moisture, a carbon monoxide kit, furnace filters for a year and allergen-free pillows. The repairs were coupled with education and a health plan tailored to the family.

By the time of the home repairs, the Gilberts had accrued about $85,000 in medical bills treating Lucas’ symptoms. They have insurance through Brad’s employer. There’s a $10,000 deductible and an 80-20 split beyond that, so the insurance company will be billed for approximately $60,000 and the Gilberts will be liable for about $25,000, nearly half their annual household income.

By comparison, Healthy Homes East Bank spent one-tenth of that—$8,400—on home repairs that, it is hoped, address the underlying cause of Lucas’ symptoms and will keep him from getting sick again.

For the first time in months, the Gilberts felt like they had a clear, feasible approach for treating the underlying causes of their son’s symptoms. When the work was completed in December, Brad says, they felt great relief.

“It’s getting better,” he says, “but it’s not there yet.”

What Would Success Look Like?

As of this writing, it’s unknown whether, or to what extent, Healthy Homes East Bank will be a success.

In the best-case scenario, the project’s organizers will document that the health and well-being of dozens of children on Des Moines’ east side were improved through home repairs that reduce asthma triggers.

But for the consortium behind the BUILD Health Challenge, the project will be dubbed a success if this new coalition in Greater Des Moines also tackles other challenging public health issues.

“It’s not about the disease; it’s about the collaboration,” said Castrucci of the de Beaumont Foundation. “A success for BUILD is not the current project. It’s that once the grant has ended, this coalition stays together and takes on the next issue.”

What could that be? Other chronic diseases that are a heavy burden on the American health care system include heart disease, diabetes, high cholesterol and high blood pressure.

For the players involved in Healthy Homes East Bank, there is a sense that they are already ahead of the curve in terms of collaboration.

“One of the truly unique and potentially groundbreaking elements of this strategy is the hospital engagement,” says Kozin of the Polk County Health Department. “The hospitals need to be applauded.”

Bob Ritz, president of Mercy Medical Center—Des Moines, points with pride to the collaboration that has gone into the Healthy Homes East Bank project. But, he adds, there is more to do.

“Our community needs and deserves more collaboration among all providers, including our health systems,” he says. “It’s simply the right thing to do.”

Gunnar Olson is a journalist with an interest in the works of cities and their residents. He is the communications manager at the Des Moines Area Metropolitan Planning Organization and former staff writer for The Des Moines Register. He and his wife, Sara, live in Windsor Heights with their 2-year-old son, Ellis.

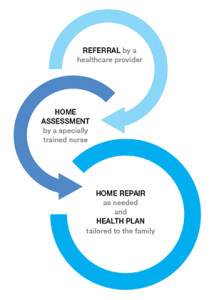

the process

Healthy Homes East Bank is a pilot project that establishes a three-step process for improving the home environment for eligible residents. The steps include:

For more information on the program, visit healthyhomeseastbank.org

or contact Claire Richmond at 515.282.3233 or crichmond@pchtf.org.

the players behind the project

Healthy Homes East Bank is one of seven pilot programs nationwide and the only one in Iowa to receive funding from the BUILD Health Challenge. The $250,000 grant is matched by $250,000 in local funding.

The project is a collaboration of the following 11 institutions in Greater Des Moines:

- Broadlawns Medical Center*

- Mercy Medical Center—Des Moines*

- UnityPoint Health—Des Moines*

- Mid-Iowa Health Foundation*

- Polk County Health Department

- Polk County Public Works Department

- Polk County Housing Trust Fund

- City of Des Moines

- Viva East Bank

- Visiting Nurse Services of Iowa

- Des Moines Public Schools

* Provided the program’s local funding

The BUILD Health Challenge is a consortium of nonprofits, including:

- The Advisory Board Co., Washington, D.C.

- The de Beaumont Foundation, Bethesda, Md.

- The Colorado Health Foundation, Denver

- The Kresge Foundation, Troy, Mich.

- The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, N.J.

The following is an open letter to 2-year-old Lucas Gilbert for him to read as an adult. Gunnar Olson wrote the letter on behalf of the dozens of people and organizations working to help Lucas and others like him.

To the future Lucas Gilbert:

By the time you’re old enough to read this, we hope you still remember the games of “baseball” you played by swinging a fishing pole at whatever “ball” your dad pitched to you. We hope you have long forgotten the hospital stays, the doctors’ visits and the many nebulizer treatments in your living room.

When you were 2, you suffered an array of asthma-like symptoms; sometimes you struggled just to breathe. You developed a deep cough. You came down with pneumonia, bronchitis, lung abscesses. Your parents and doctors treated your symptoms. They grew frustrated searching for the underlying cause.

They came to believe that your house was likely to blame for your symptoms. Like many older homes, it contained several “asthma triggers,” such as excessive moisture, bathrooms without fans and a gas stove without ventilation.

So to improve your health, we fixed your house.

This seems so logical, so simple, that surely you’ll think this is the way things have always been. But in fact, you were the first child treated as part of a potentially groundbreaking pilot program called Healthy Homes East Bank. With national and local financial backing, the program focused on repairing homes to improve public health in the 50316 ZIP code of Des Moines, one of the city’s older neighborhoods, where children have asthma at twice the rate as the rest of the state.

Surprising though it may seem to you now, the Healthy Homes East Bank program represented a remarkable feat for its day. Remarkable, that such a seemingly simple solution was so incredibly complex to execute. Remarkable, for the sheer number of people and organizations, invisible to you as a child, who had to step out of their routine roles and join forces for the betterment of public health. Remarkable, that it could be the beginning of a new level of collaboration among organizations whose actions affect public health.

But most remarkable of all is that it’s remarkable to begin with. By the time you are old enough to read this and comprehend what made Healthy Homes East Bank possible, we hope that such an approach to health care is ordinary and not the least bit remarkable. We hope, instead, that the experiences and the lessons learned will be carried forward, so that our breakthroughs are your everyday practices.

Gunnar Olson is a journalist with an interest in the works of cities and their residents. He is the communications manager at the Des Moines Area Metropolitan Planning Organization and a former staff writer for The Des Moines Register. He and his wife, Sara, live in Windsor Heights with their 2-year-old son, Ellis.