Writer: Sophia Ahmad

How do we come to be who we are? Lives are built day by day, but they hinge on memorable, transformational details—a mentor, a discovery, a dream or a gut check. Many factors shape us, but only a few we recall that define us. We asked several noteworthy people to reflect on what steered them to their life’s path. Their answers, fascinating and enlightening, are condensed here.

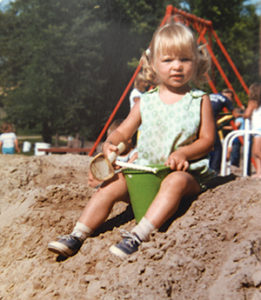

Stephanie Jutila

President and CEO, Greater Des Moines Botanical Garden

Jutila grew up in Cloquet, Minnesota—“the home of Frank Lloyd Wright’s one and only gas station.” For as long as she can remember, she’s been interested in plant life, a passion fostered in childhood

on her family’s 21 acres of land.

I remember being outside from a very young age. Our land felt safe because it was a big piece of property, yet we knew where the house was. We grew raspberries, strawberries, tomatoes, peppers and cucumbers as well as hostas and daffodils. I tried to do everything with plants; I knew that they brought me a lot of joy.

I had a brother who was five years younger, and a lot started to happen in our sandbox. I used his Tonka trucks—combined with things I would discover in the woods, like moss—to help me shape formations in the sandbox. What I do now goes back to the boundaries of that sandbox: It was a blank canvas and I could create. I had a fascination with things that would reflect nature and be inspired by nature.

I worked in a greenhouse until I went to the University of Minnesota. I spent time with a landscape architect in Minneapolis. I was intrigued by the notion that I could work on a garden—I might be there for a week, but after that I would leave. I decided that working on temporary projects wasn’t enough; I needed to work on landscape projects that I could stay with for a long time and that require patience and perseverance.

Jonathan Sturm

Concertmaster and first violinist, Des Moines Symphony

Music has been Sturm’s calling for his entire life. As a high school sophomore, he played his first violin solo with the Virginia Symphony in Norfolk, giving him a taste of the spotlight: “I loved it and hoped to remain in it.” As a student at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Ohio, he recalls, “I began seriously trying to understand how the violin works, how to navigate its space, how to plumb its depths of expression. … They were hard years that contained lots of depression that I could not make the violin sound as I wanted it to. My mother encouraged me often to change careers. But there was some kind of drive pushing me forward in music.” Push forward he did:

1985 brought a pivotal event for me. I was teaching music history at a Jesuit high school in Rochester, New York, making a salary of $3,000 for the year. Because of the teaching schedule, I was not able to hold down another job, and so I was living with the priests in their monastic residence because I could not afford an apartment. I decided to take a Fort Worth Symphony audition. I started practicing, but I was still learning some of the repertoire the night before the audition. The flights and hotel cost $350 or so, which was fully 10 percent of my annual salary. I did not make it past the first round of the audition, and returned to Rochester really angry—not with the process of the audition, but with myself. I said, “I will never take another audition that I am not 110 percent prepared to the best of my ability. There may be better applicants, but not better prepared ones.”

I have kept to that work ethic pretty much ever since, auditions or not. Concerts, lectures, speeches, I try to be on top of every moment of my life. That has paid a better dividend than my talent, I am sure, and it is a message I send to all young people.

Yogesh Shah, M.D.

Broadlawns Medical Center

A physician shortage brought Shah, a native of India, to Mount Ayr, Iowa, in 1994. He moved to Des Moines in 1997 and has specialized in geriatric and memory care as well as global health.

I grew up with extended family in Mumbai. That means that my grandparents, parents, siblings, uncle and his wife, unmarried aunt—we were all under the same roof. Taking care of elders was important. We didn’t have a physician in our family; it was both the family need and the social respect that led me into medicine. In Mumbai, if you get good grades, you can get into medical school. There was a lot of respect in India for physicians and teachers. So I became a doctor. Like many people in the same situation, although I was in the upper-middle class, I left India to come to the United States. If I hear about a good opportunity, I just do it.

Virginia Croskery Lauridsen

Acclaimed soprano and assistant professor of music, Simpson College

Although Lauridsen’s artistic talents were clearly evident when she was a child—she played the violin and French horn as well as sang and acted onstage—she was also a stellar student in math and science. So at first she set her sights on engineering.

I went to Northwestern University for biomedical engineering but quickly realized it was not for me. I was bored. I transferred to theater and realized that that was not for me, either; it was too experimental. So, I went into voice. I wanted to be Julie Andrews—to sing in musicals—but my teachers kept pushing me to opera. I naturally have a really big voice. It’s nothing I did; it’s what God gave me.

I auditioned for the Chicago Symphony Chorus, which was a big deal. I started in an unpaid position as a second alto but then was offered a paid soprano chorus position. To sing as a soloist with the Chicago Symphony when I was 21—I think at that moment, I realized that I could have a career as a singer. At that moment, there was nothing I loved more; I sang with a joy from my heart.

China Wong

Owner, Salon Spa W

Before going into the salon business, Wong worked in the finance industry in Chicago. Her father, a first-generation American and self-made businessman, and mother “felt that I had arrived; that was the dream they had for me.” But Wong soon discovered that their dream wasn’t her dream.

I knew right away that in corporate America, even though it was a well-paying, great job, I was missing something that filled my heart. I really wanted to be an entrepreneur, but I didn’t know what to do. I needed a passion. I was yearning for that opportunity to create a concept from zero to 100.

One day, I went out to lunch with friends from the office, and the whole time, we talked about blow-drying hair.

I was telling them about the Mason Pearson brush and special blow dryers. One friend bought some of the products we spoke about and came bouncing into the office the next day saying, “Thank you, I like how nice my hair looks!” There was something in her that was so confident. It made me feel really good. …

So I enrolled in the Aveda Institute in Chicago and moved from my Lincoln Park apartment with a rooftop deck into a 325-square-foot studio. My bed touched my dining table, which also touched my dresser. I went to school during the day and bartended at night to make ends meet. I wanted to save every single penny I was making to invest in opening my own salon.

Alfredo Parrish

Senior partner, Parrish Kruidenier

Parrish grew up in Camden, Alabama, where he attended segregated schools prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Good teachers and his Presbyterian minister served as positive role models during his youth, he says. His teachers “pushed us to do our homework and they all took an interest in the fact that if we didn’t do well, they would care,” he recalls. “I didn’t want to disappoint them by failing.” Likewise, his minister “helped me by helping me read a lot. He loved to read and I had a knack for wanting to read, and it was a pivotal point for influencing me.” His parents, though, provided the strongest influence.

My parents put me on the straight and narrow. My mom always had this great quote: “Remember, you’re not better than anyone else, but no one else is better than you.”

They were teachers at Camden Academy, where I went to school. It was a mission school, funded by the Presbyterian Church in the North. Eventually, the states took the schools over, and that’s when they could begin to control the teachers and the activities they were involved in. My parents wanted to make things better for minorities in the South. People respected them in the community and listened to things they had to say.

Both of my parents got fired from their teaching jobs in 1966-67. My mom taught second grade, and she was fired for organizing a student protest against segregation. My father taught science in the fifth grade and he was an elementary school principal. He got fired for running for the Board of Supervisors in his county as a black man. Even though they were treated unfairly, they respected people as human beings. Watching how they interacted with people was always a good marker for me. After they were fired, my mom went to New York to become a housekeeper to make a living. My dad did whatever he could to make a living.

At the time, I was in my junior year at the University of Dubuque—I was a pre-med major. I love kids; I always wanted to be a pediatrician. I always thought that being a doctor would be a good profession. But when my parents got fired, I switched majors and decided I wanted to go to law school.

I wanted to help people who have been treated unfairly.

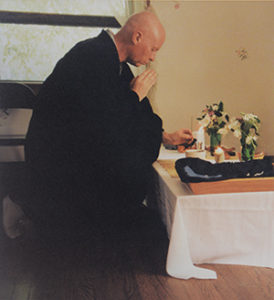

Eido Espe

Buddhist priest, Des Moines Zen Center

The grandson of an evangelical minister, Espe was raised in Radcliffe, 60 miles north of Des Moines. He enlisted in the Army, served in Vietnam and returned in 1970 “disillusioned and angry,” he says. His best friend, farm activist Dixon Terry, gave him a book on Zen Buddhism. “It spoke to me,” Espe says. After a romantic breakup, he traveled to California to attend a monastery and learn about meditation, later returning to the Midwest to raise his family. Eventually, he became interested in becoming a Buddhist monk.

In the late ‘80s, my friend Dixon Terry and I worked together on a farm in the Greenfield area. I thought I would never pursue being a monk because we were creating this farm. Then Dixon was tragically struck by lightning and killed.

My interest in Buddhism is rooted in loss. I wouldn’t be a monk today if not for the losses of an early romantic relationship and my friend Dixon, the most brilliant person I have ever known. I was ordained in 1999, and Buddhism has helped me understand that loss is inevitable. The idea of impermanence is important in Buddhism.

Part of the center of our practice is meditation, which is not an escape but sitting down in the middle of your life as it is and being there with it. You begin to understand that your thoughts are not permanent; they change. To sit down and just look at your mind is hard. It’s really peeling away at a lot of emotions and trauma and peeling away a lifetime of loss and regrets.

Mark Tauscheck

Television reporter

Tauscheck recalls struggling with math and science, but a seventh grade teacher praised his writing. “I remember the validation I felt,” he says. And in high school, he and a buddy produced a video for their Spanish class, starring Tauscheck as Spanish late-night host “Juany Carson.”

My father videotaped us in the basement. My classmate kept coming out as a Mexican boxer, then a zookeeper with some fake animals, and I just interviewed him in my broken Spanish. That was my first time interviewing someone and it was really fun. Watching the tape in class, everyone started laughing—people had tears in their eyes. Other students heard about it and wanted to see it. Other than hearing it from my parents, it was rare for me to be told, “Hey, you did something really well.”

When I went to Marquette University, I didn’t know what I was going to do. I would never have gotten into the television business had it not been for Bob Nenno, a reporter from the local NBC affiliate who taught a TV reporting class the last semester of my senior year.

I was about to graduate without a resume tape, which you need to get a job. But he forced us to do a story every week. At the end of that semester, which was at the end of my college career, I was able to select three of the least-worst stories for my resume tape. I am eternally grateful. If he had not taught that class, there is no way I would have gotten a job.

Steve Berry

Actor

Berry’s first role was the lead character in a kindergarten play. At 12, he was cast in “Jabberwock” at Des Moines Community Playhouse. Performances followed at Roosevelt High School. But when he enrolled at Drake, where his father was a professor, he studied political science and law.

Halfway through law school, I knew I didn’t want to practice law. Drake was doing “Hair,” and I thought, “I’m going to go try out.” I figured I wasn’t going to study for the bar, so I thought, “Why not study lines instead?” I played Berger, one of the two male leads. I had never acted at Drake during undergrad, and I waited until my third year of law school to do a show there.

And thankfully, great roles came around. That same year, 1986, was John Viars’ first year at the Des Moines Playhouse, and I auditioned for “West Side Story.” He liked my voice and took a chance on me. After that, it was a string of shows.

Sarah Dornink

Sarah Dornink

Clothing designer and owner of Dornink

Dornink grew up in the clothing business: “My mom did custom dress design out of our house and would have little sewing classes for my friends and me when I was in third grade.” Although she “was surrounded by design and was good at it,” she wanted to be a surgeon and enrolled at the University of Iowa.

One day during a math class, I was sketching dresses instead of taking notes. In that moment, it hit me: “I don’t want to go to medical school; I want to go to fashion school.” So after graduating with a degree in biomathematics, I applied to Parsons School of Design in New York and got in. But when I got to New York and understood how much Parsons would cost, I un-enrolled and temped at American Baby magazine. Through that job, I applied for a real job—my first was as a production manager for accessories designer Elizabeth Gillett.

I enrolled in the Fashion Institute of Technology. I would create designs in New York and send them back to my mom, and she would sew them and put them together. She would say, “Oh my gosh, Sarah, people are really excited about the design that you did.”

I just always assumed I would stay in New York City. But, I moved to Des Moines. It was a combination of having a business with my mom and the energy of having two designers at the same place. And, I started dating a boy who was from Des Moines. The two were a big enough draw to return here.

Larry Cleverley

Organic farmer

In 1980, Cleverley was a national credit supervisor in Chicago and started going to farmers markets. In 1981 he transferred to New York City and was on the young executive fast track. But his interest in food called to him, from the family cooks of his Iowa childhood to New York’s huge Union Square farmers market.

When I lived in New York, I began to spend time with a farmer, Ray Bradley, a former chef who grew things that I had never seen before: fingerling potatoes and heirloom tomatoes, and a really great variety of food that broadened my palate and cooking. I would drive up to his farm, about 50 miles north of New York City, to help him. That made me think, “I can do that!”

When my paternal grandmother died in Iowa in 1994, I stayed with my grandfather for a time and discovered that Iowa wasn’t as mundane a place as I remembered as a kid. And so I went back to New York and I started thinking, “How can my wife and I move back to Iowa? Would it be possible? If we moved back, what would we do?”

In 1995, I visited Des Moines’ Downtown Farmers’ Market and talked with Doug Smith, then the chef at Cosi Cucina. I asked him if a local farmer came in to sell him produce, would he be interested in it? And he really encouraged me to make the move and to do some of the things that I had seen, eaten and cooked in New York. In the fall of 1996, we packed up and moved to Iowa.

Calla Devlin

Author

In high school, Devlin says she became infatuated with globe-trotting correspondents and enamored with their lifestyle. “I remember thinking that being the truth-teller was very appealing,” she says. “I was 16 and a journalism junkie.”

I went to college to study journalism, but I was appallingly bad. As part of that major, I had to take a fiction class. I was always a big fiction reader and I loved to write, but I didn’t see myself as a fiction writer. I caught the bug. Part of it is that I received great feedback. Three teachers in particular told me I had a gift to write.

It wasn’t until halfway through college that I realized how important it was to have a voice and to be a storyteller. I dedicated myself to books. I became a bookseller—anything I could do with books. I decided to get an MFA in fiction, and they taught me how to publish short stories, which is still a daunting thing. The acceptance rate is so low. I knew that writing was a compulsion and not a hobby.

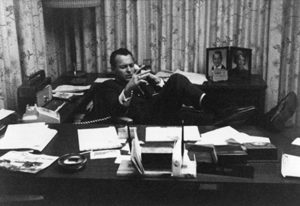

Bill Knapp

Bill Knapp

Chairman emeritus,

Knapp Properties

One of Greater Des Moines’ most well-known and influential business leaders, real estate mogul Knapp grew up on a farm in southern Iowa, where he milked cows with his brother and father, but he knew he didn’t want to become a farmer. “You couldn’t control your life because you couldn’t control the weather and you couldn’t control the price” Knapp recalls “I wanted to do something where I had some control.” Leaving the farm life behind, he became a restaurateur.

In 1947, my wife and I bought a restaurant in Allerton, Iowa. We called it the I and B Cafe (the “I” came from my wife’s name, Irene, and the “B” from my name, Bill). For a few months, we served breakfast, lunch and dinner. After a few months, we realized that it wasn’t what we wanted to do. It was too much work. The restaurant business is tough; anyone who can run a successful restaurant can run anything.

We decided to sell the restaurant.

We decided to sell the restaurant.

I listed the company with W.K. Brewer, a business broker in Des Moines. In a few weeks, he said he had a potential buyer. He was busy and asked me if I would meet the potential buyer at the restaurant and show it to him. I took him down to Allerton and he bought the restaurant. I made the sale and the broker got the commission. As I thought on it later, I decided real estate might not be a bad way to make a living.

Benjamin Gardner

Artist

His mother gave him a sketchbook when Gardner was just 2 years old, and he grew up fascinated by art. He went to Millikan University in Decatur, Illinois, to study graphic design, but found it too restrictive. After dabbling with philosophy and English majors, he met his mentor and found his place in the art department.

I felt most at home at my studio classes, because I felt that I could bring other classes and influences into my studio classes. Lyle Salmi was my painting, printmaking and drawing professor at Millikan. He was very engaging and pushed very hard. He said, “For every 100 pieces of art you make, one will be good.”

There was a good community of artists and art students there. It encouraged me to spend my extra time in the studio, and when I graduated, I decided to be a professional artist, if I could. I tried to submit five applications a week to galleries and juried shows. I had a few exhibitions and was able to sell a few paintings. It was in graduate school when I was sure I was going to be a studio artist and that I was going to do art.