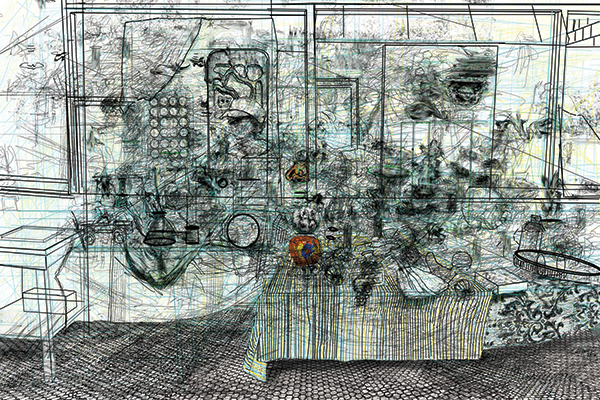

Above: Detail of “Splatter,” which appeared on a local commuter bus as part of a public art project. Artist Brent Holland says to “picture the bus having just splashed through a river of paint.” The vibrant work is a departure from the portraits and figurative pieces that were the focus of Holland’s previous work.

Writer: Brianne Sanchez

Creativity is messy. For artists who are curious about trying unfamiliar mediums, exploring unexpected opportunities and reaching expanded audiences, the frustrations and setbacks inherent in the process can outnumber the breakthroughs. For a while, it’s muddling through. And then, the vulnerability that comes with presenting something new. Three established artists recently offered dsm a peek into their studios, all located in the Fitch Building downtown, where their latest work is taking them in new—and sometimes surprising —directions.

Brent Holland

Creating Augmented Art

After gaining recognition for portraits and figurative work, Brent Holland’s entry into the world of abstract digital art is a radical shift. In place of brush strokes and detail are swirling pools of color that have become the trademark of his 3-D sculpting. He’s also experimenting with augmented reality functions, and even his more traditional drawings incorporate new mediums, like plastic films that create dimension when layered.

After gaining recognition for portraits and figurative work, Brent Holland’s entry into the world of abstract digital art is a radical shift. In place of brush strokes and detail are swirling pools of color that have become the trademark of his 3-D sculpting. He’s also experimenting with augmented reality functions, and even his more traditional drawings incorporate new mediums, like plastic films that create dimension when layered.

As associate professor of art and visual culture in the College of Design at Iowa State University, the 39-year-old Holland is continually interacting with industrial designers and architects. He became more interested in working digitally after watching graphic artists for several years and wondering if he could apply similar processes to his art.

Inspired by Photoshop, his more recent pieces employ a layering effect. He prints multiple digital drawings that are stacked and fused by glue or sticky film.

Holland also is working with design students to embed art pieces with image tracking capabilities; when viewed through a smartphone app he’s developed, called “Studio Holland,” a 3-D version of the piece pops on the screen.

“I feel like augmented reality is adding another layer of depth, and the viewer has to participate to unlock the experience,” Holland says.

He says exploring new methods of art-making meant moving beyond the expectations his audience might have of him as a fine artist. “The moment I let go of that, it was so freeing,” Holland says.

His departure from the work that helped earn him a following was nerve-wracking, he says, but essential for his creative growth. Standing before pieces that pop with a palette of vibrant reds and yellows and blues, Holland exudes excitement.

“I’ve never felt happier,” he says. “[Before], I always felt like I was going to the studio out of duty. This is so liberating.”

By adopting digital painting for public art projects—like a proposal to paint the Fort Dodge Grain Terminal in an interactive graphic—he can scale up his work and try projects that never would have been possible using his previous mediums.

“I’m trying to find this magical realist space of 2-D and 3-D meeting in such a way that there’s a wonderment in how that could possibly take place,” Holland says. “I’m trying to incorporate this technology in a way that will educate us as well as be cool.”

Large-scale public work has included the Des Moines Public Art Foundation’s wrapped DART “Art Bus.”

A smaller version of the work “Splatter”—designed to look as if a bus ran through a river of paint and got splattered all through it—hangs in his studio.

“I’m portable,” he says. “I can go big or small. A whole new frontier has opened up.”

Above: Brent Holland’s “Studio VII” (2016) is a multi-dimensional work combining digital and traditional media. Each drawing was printed on a separate sheet of clear plastic; the sheets were then stacked together.

Amenda Tate Corso

Blending Art and Science

The space under the 10-foot pop-up tent inside Amenda Tate Corso’s light-filled studio is commandeered by her “Manibus” project. The tent is typically used at art festivals, where Corso exhibits her jewelry and metal wall sculptures. But this new project needs room to roam.

The space under the 10-foot pop-up tent inside Amenda Tate Corso’s light-filled studio is commandeered by her “Manibus” project. The tent is typically used at art festivals, where Corso exhibits her jewelry and metal wall sculptures. But this new project needs room to roam.

Originally conceived for an artist-in-residence program offered last year through Ballet Des Moines, Manibus involved Corso cobbling a tiny image-drawing robot from components that came in her kids’ make-your-own-invention kit. A smartphone communicates via Bluetooth; the robot draws according to the arm motions of the phone’s handler. The resulting colorful squiggles are more Duchamp than Degas—appropriate, as the artistic process stems from Corso’s tinkering tradition.

“For me, it’s not really different,” she says. “I’m applying the same approach, the same blend of art and science.”

Corso, 42, worked toward a mechanical engineering degree at Iowa State before deciding that a future in washing machine design wasn’t something she could get excited about. On a whim, she took a metalsmithing course. “After that I was kind of sold,” she says.

Corso decided to search for more “emotionally evocative” work and completed a BFA at Metro State University in Colorado, returning to Des Moines in 2011. Since then, she primarily has worked in metal, making jewelry and decorative pieces.

Then she won the Ballet Des Moines residency. “I wanted to create a project specially for working with the ballet,” she says. “I wanted something that was going to tell the story. I knew that once it was started, it had legs to go other places.”

That’s not to say the start was smooth. Corso called developing her Manibus a continual exercise in problem-solving, in failing and persevering. She had to figure out how to keep the paint pen in place, and create parameters to keep the wheeled machine on the paper—among myriad tweaks to the design.

Following her residency with Ballet Des Moines, Corso was invited to collaborate with the Colorado Ballet. Her goal with that project was to convey her optimism about the future of machine and human interaction, and to create opportunities for finding meaning in the digital revolution.

“I like to think of [the Manibus project] more as a translation of the emotion, not just where you’re going,” Corso says. “Everything we’re doing is somehow marked by a record. We’re recording our steps, our sleep. But while we’re quantifying all of these things, are we really seeing ourselves when we’re looking at this data?”

Corso is learning basic coding to develop a more advanced Manibus that can create mirror images of a design, a reflection element she likes to create to make more sense of the movement.

“In order for artists to stay relevant, we need to have a finger on the pulse of what is going on,” Corso says. “Part of it is just being curious and continuing to make discoveries.”

Above: The painting “Five Years Out,” right, was created by Amenda Tate Corso operating “Manibus,” a tiny image-drawing robot, shown above, that she created out of components from her kids’

toy invention set.

Larassa Kabel

Exploring Performance Art

“This year, I’ve been playing more and trying some stuff that’s been on the back burner,” says Larassa Kabel in a studio she shares with her two Boston terriers, her celebrated large-format falling horse drawings and, now, piñatas designed as life-size albino deer.

“This year, I’ve been playing more and trying some stuff that’s been on the back burner,” says Larassa Kabel in a studio she shares with her two Boston terriers, her celebrated large-format falling horse drawings and, now, piñatas designed as life-size albino deer.

The deer were created for a group show curated through Transient Gallery during last year’s Art Week, and used in Kabel’s first performance piece, “Bystander.” In it, she wears a blindfold and whacks at a buck piñata that is suspended by its hindquarters.

The piece was a quick turnaround; Kabel had only six weeks to come up with the new work. The tight time frame also presented an opportunity for the artist to confront her anxiety surrounding current geopolitics and the tectonic shift in her personal life, as her son graduated from high school.

“I feel like the world is a little out of control, and [making art] is something that I can control,” Kabel says. “A lot of stuff I care about is under attack. I had been thinking about the dynamics of power.”

She began paying more attention to the Black Lives Matter movement, racial bias and white privilege, beyond her feminist worldview.

In “Bystander,” Kabel explores what it’s like to be the person who is the enforcer. Using a piñata as a metaphor, she shows how a passive audience can reap the spoils of systematic oppression, even if they aren’t the ones actively swinging the stick.

“It was so uncomfortable,” Kabel says of the 2017 Art Week performance, which she plans to re-create at a nighttime, wooded location for a short film by Iowa Arts Council fellow Jack Meggers. “It’s good to go through something really scary sometimes.”

It wasn’t just the theme of the work that posed a challenge. Tactically, construction was a trial-and-error process that at one point involved sanding spray-foam insulation off her hands and at another led her to shop for eyes through a taxidermy catalog.

“I draw very well,” Kabel says. “It’s concentrated work, but it’s familiar enough.” Building a deer piñata was a much different enterprise, she says: “A deer is a really hard thing to make from scratch.”

Kabel, 47, will continue to incorporate deer species into her work. Moberg Gallery has commissioned her first sculpture, a public art piece tentatively slated for the corner of Ingersoll Avenue and 42nd Street. The bronze cast caribou will explore the interconnected nature of love and loss; passers-by will be able to hang small memorials from the antlers, which will be molded from a set Kabel’s father harvested years ago. Fundraising for the installation is in process.

The proximity of Kabel’s studio to the Pappajohn Sculpture Park—her windows look onto the southwest corner—has inspired her to embrace interaction with her work. Park visitors “always touch the art. They just do,” she says. Likewise, her new sculpture “is about letting public art be public.”

Above: In “Bystander,” her first piece as a performance artist, Larassa Kabel whips a piñata designed as a life-size buck as a way to explore what it’s like to be an enforcer. Using the piñata as a metaphor, she shows how a passive audience can reap the spoils of oppression, even if they aren’t the ones cracking the whip. Photographer: Ben Easter.

Above: Kabel says performing “Bystander” was a way to confront her anxiety about current geopolitics. “It was so uncomfortable,” she says. Photographer: Ben Easter.