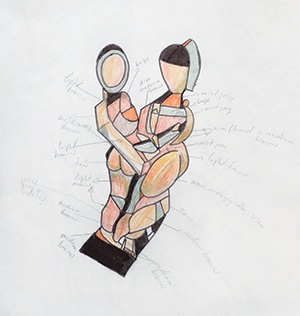

Above: Artist Annick Ibsen begins her ceramic work by sketching her concept. “Once I am satisfied with my sketch,” she says, “I roll out slabs of clay and cut out pieces very much like a pattern that I assemble.”

Writer: Kelly Roberson

Photographer: Duane Tinkey

At her first ceramics class at the Des Moines Art Center, Annick Ibsen’s instructor taught students how to make a box.

Isn’t artistic creativity defined, in part, by thinking “outside the box?” What is a box, anyway, but straight planes, right angles and rigid uniformity? The instruction, however, would prove foundational to Ibsen as an artist. “The instructor was meticulous about how to do it—how to finish the seams, for example,” she says. “I’ve never forgotten that.”

Ibsen, 52, would go on to finish that box, and then develop her own aesthetic as a sculptor and painter. She has taken her knowledge, her work ethic, her talent and her expansive view of the world to push her work from local recognition to the national landscape and to push herself to new creative heights.

“She’s getting bigger and bigger shows, and that’s becoming a norm for her,” says Barbara Vaske, director of the Ankeny Art Center. “She’s at the beginning of her going-to-be-famous stage.”

Always an Artist

Ibsen’s studio—a sunny, multi-roomed space in her family’s century-old South-of-Grand home—is thousands of miles from the French native’s upbringing. Her father’s job as an oil engineer took the family to such far-flung locales as Libya and Indonesia.

For Ibsen, her time at an American high school in Tripoli translated into dreams of studying in the United States; she did, thanks to a scholarship from Eureka College in Illinois, where she graduated in 1987 with a degree in marketing. Initially she was convinced that hers would also be an expat life, and for a while it was: Graduating from a French business school in 1989 led to financial jobs abroad, including one in Hong Kong—where she met her husband, Craig—and others in India, London and Chicago.

But always in her downtime, Ibsen enjoyed painting as a self-taught hobby, and when she and Craig and their two children relocated to Central Iowa, she decided to challenge herself in a new medium: clay.

In Ibsen’s early work, you can see her puzzling out the material—how to fight gravity, balance the weight of the sculpture, ensure stability. Ibsen mastered that challenge the old-fashioned way: She practiced. Then she practiced some more. She took classes, including those offered at the Des Moines Art Center and Ankeny Art Center, and worked at RDG Dahlquist, a collaborative studio on Des Moines’ south side. She asked questions and soaked up what she could from people who knew more than she did.

“I’m a firm believer in the Malcolm Gladwell idea of working 10,000 hours,” she says. “In a way, it’s an imposition to be an artist because it never leaves you—you work all the time. I work at it every day, at least eight hours a day.”

A Transformative Year

Ibsen served as an artist in residence at the Ankeny Art Center for a year spanning 2015-2016, and the experience gave her the confidence she needed to create her own home studio. In Ankeny, once or twice a week for a year, Ibsen came in and managed the studio and assisted students. “She was doing ceramics at RDG Dahlquist and making some fabulous things,” says Vaske, adding that the learning took place on both sides. “She mentored our people and we mentored her.”

Even then, Vaske could see Ibsen’s themes—jazz, the human body, cubism—and knew that the sculptor was ready to go to the next level.

“Very few sculptors and almost no ceramic artists are doing cubist ceramics, and that makes her work unique and of a national level,” Vaske says. “It’s well-built and beautiful, and she has a deep understanding of how cubism operates. Most ceramics people can’t paint and draw, and that brings a new dimension.”

An Artist’s Process

When Ibsen begins a new piece of work, she starts with an idea, a theme and a title; then she sketches extensively. The sketches, which include views of the piece from all sides, then lead to building; for Ibsen, that’s limited by the size of her kiln. Less frequently she’ll build a sculpture in pieces and epoxy them together, but the build remains her favorite part. “It’s much tougher than painting on straight canvas—you’re adding another level of complexity,” she says.

That’s a simplification of the process, of course: Sometimes the start-to-finish takes years as she thinks and refines. And her work tends to reflect certain constants—self-love, for one example; cubism, to name another. “Even as a kid, I was interested in cubism,” Ibsen says. “My art doesn’t evolve on a lineal path. I’ll take big steps but do things incrementally, but then all of a sudden decide to explore a new topic. There’s a lot of observation, but to me it’s not just objects that have shape. Emotions have shape.”

And she always pushes herself; this year it’s been solo shows and juried exhibits. “This year I wanted to understand the vibe of art exhibits, and something interesting happened for me,” she says. “I realized how important it was to see and talk to other artists, to go to museums, to connect and co-exist. It’s stimulating to see that and feel that energy.”

Titled “Nude,” this figure stands 21 inches tall. It is, the artist says, “the culmination of my interpretation of cubism in 3D. It decomposes colors, structure, angles and perspective and uses the traditional cubist palette of colors.” The challenge, she says, was to make a feminine nude “in spite of the geometry.”

“All my sculptures are hollow,” Ibsen says, including the delicate “Reclining Nude,” another exercise in three-dimensional cubism. It measures 14 inches tall, 18 inches wide and 19 inches deep.

“The Lovers”

An annotated sketch of the sculpture “The Lovers” shows the final stage of Ibsen’s process. After creating a sculpture, she sketches it and adds paint colors to the drawing. “This 2D representation helps me decide where I want to place colors,” she says. The sketch also helps her confirm that the sculpture’s final colors, after firing, are true to her intentions. “With ceramics, you never know if the piece will work out until the final firing,” she says. “It can be emotionally taxing.”

The two-piece sculpture “Closet Love” is about “self-love,” Ibsen says. “It is not so much about closeted love as much as about the need for human beings to love themselves so they can love one another better.”