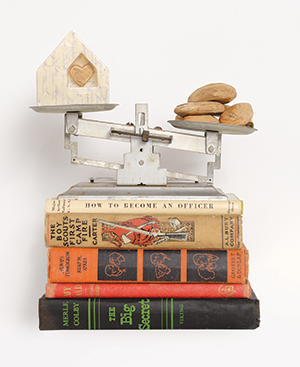

Above: How place shapes art is a concept that Franklin is exploring. Creating art about North Texas while she’s living in Iowa has caused her to ask, “Does the work translate no matter where it happened?”

Writer: Brianne Sanchez

Photographer: Duane Tinkey

You will never meet Julia Franklin’s father. He committed suicide in 1990. But through exploring her upcoming installation “Picking Up the Pieces,” you may come to know Johnie Andrew Tucker better than most in Wichita Falls, Texas, where he raised his family, worked as an accountant, ushered at his church—and lived as a closeted gay man.

Franklin, who was awarded a 2018 Iowa Arts Council Artist Fellowship for her work, has created a mixed media portrait from ephemera. Correspondence, clothing, photographs and trinkets tell the story of her father as she saw and loved him. But the installation also unravels unexpected dramas that lay dormant for many years after his passing: Debts, depression, domestic deceits and death threats shadow his personal history.

“As an artist, our work is always personal, but sometimes that’s not as obvious to the audience,” says Gary Heisserer, associate dean of academic affairs at Graceland University, where Franklin has been on the faculty since 2001. “In this, it’s unmistakable. You stand in front of the suicide note [Franklin] found from her father. I don’t know what’s more intimate or personal than that.”

By airing secrets that once shamed her family, Franklin, 44, hopes to spark conversations about mental health, memory and identity to help others find a way through loss and grief. As she sifted through letters, she made connections between the man her father was to her and the private pressures that may have driven him to take his life.

“In a way, he was so one-dimensional,” Franklin says. “This adds layers.”

While unpacking boxes that had been hidden from her for more than 25 years, she gained deeper insights into the lives of her adoptive parents. References to “business with a plumber” revealed her father had been involved in a murder mystery that was later made into a book and multiple made-for-TV movies.

“Is it a side story?” she asks. “Or is it the main story?”

Artist and Audience

During the recent run of “Fun Home” by Iowa Stage Theatre, Franklin hosted a pre-show talk about her work. Parallels between her own family dynamics and the dysfunction portrayed in the Alison Bechdel play created space for conversation.

It’s this sincere interplay between artist and audience that made Franklin a standout candidate for the Iowa Arts Council fellowship. She has discussed her work in partnership with One Iowa and at a variety of “Meet the Artist” talks.

Franklin “is setting up an experience to be relatable to the public, despite the tough and emotional topics she’s dealing with,” says Veronica O’Hern, who manages the Iowa Arts Council’s fellowship program.

The fellows are encouraged to work across disciplines, and Franklin’s connection to theater is an easy leap. Her installations, as Heisserer observes, are reminiscent of a set and props without the actors. He encouraged Franklin to develop a play, “Keeping Up Appearances,” which will be read during her upcoming exhibit at Graceland.

“[Franklin] thinks in a very theatrical way,” he says. “Her work is visually striking, dramatic, with a pretty heavy thematic edge to it.”

Found Things

Franklin, who received a BFA from Midwestern State University in Wichita Falls and an MFA from Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, worked in community outreach at the Dallas Museum of Art before moving to Iowa. Her work has always focused on found things, whether from nature or from artifacts of domestic life. “I take these objects and try to highlight their beauty by creating experiences for people to explore,” she says.

Her methods were honed during ambling walks with her preschool-aged daughter (now 16). “She taught me to collect and pay attention,” Franklin says.

Today, she’s invigorated by the opportunity the fellowship has provided to collaborate with colleagues and build connections across the state. She recently relocated to Des Moines from Lamoni and secured space at Mainframe Studios. There, she’s able to connect more deeply with a community of artists and expand her work. She continues to commute four days a week to campus, where “Picking Up the Pieces” will be shown Jan. 14-March 1 at the Helene Center for the Visual Arts.

Visitors will move through multiple spaces to experience the exhibition. They are invited to crawl through a blanket fort like the ones Franklin’s dad built during her childhood and open drawers in a desk whose files she re-created to expose the darker themes of the work. Vignettes with real artifacts that chronicle her father’s life are interwoven with more interpretive collections that evoke the shattering of trust and security Franklin felt at the time of his death.

Catharsis, closure and a new closeness to family have all been the rewards Franklin found from wading into her father’s past. Tucked within her father’s papers were also clues about Franklin’s origins. Adoption papers she had never pursued while her parents were alive tell her that her birth family included two older siblings.

Never shy about using her personal experiences to inspire her art, Franklin smiles at the thought of what revelations chasing down her own past could bring: “That’s probably a whole other body of work.”

This portrait of artist Julia Franklin’s father is meant to convey their overlapping emotions—the despair that must have led to his suicide and her grief at realizing he was gone.

BY THE COLLAR

In Franklin’s memories, her father is always in a dress shirt. She constructed this homage by preserving his old letters in beeswax before cutting and assembling them. The process renders the paper more transparent. Letters were scanned for posterity.

AiRING THE FAMILY LAUNDRY

After the death of Franklin’s father, his belongings were removed from the house and her mother rarely spoke of him. Franklin’s cousin Ruthie, whom she hadn’t seen in 15 years, drove from Oklahoma City to Iowa City to deliver the boxes of letters, pictures and old ties that had been kept in storage.

“How did this exist and we didn’t know?” Franklin asks. “We didn’t have any of this at all.”

She pored over the contents, and instead of pressing photos into scrapbooks, she used the pieces to inspire an interactive art exhibition, gaining closure through her creativity. “Through the process of collection, reflection, and creation, I’ve discovered more about myself, our society, and our planet, but I never imagined it would become so personal,” she wrote in her artist’s statement.

DOCUMENTING THE DOMESTIC

Nature and the concept of home are themes that carry across most of Franklin’s work. She has constructed nests and assembled her found collections to make public the private and precious. She honed her process when her daughter was young and the two would take walks, observe and pay attention to little details together.

INSTALLATION

“Picking Up the Pieces”

Jan. 14-March 1

The Helene Center for the Visual Arts

Graceland University

1 University Place, Lamoni, Iowa

A reception will be held in the Helene Center on Jan. 25 from 5 to 8 p.m.

There will be a reading of Franklin’s play, “Keeping Up Appearances,” in the installation space Feb. 8 at 7:30 p.m.

Franklin will give a talk Feb. 18 at noon in Carol Hall.

All events are free of charge and sponsored by the Iowa Arts Council. Gallery hours are from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Monday through Friday and from noon to 5 p.m. on the weekends or by appointment.

“Shattered” consists of a ceramic house (modeled as an enlarged Monopoly house and covered in a suicide note replica) paired with a shattered mirror. The piece reflects how, following her father’s death, Franklin’s family sealed themselves in, trapped by shame and silence. Trust and security were shattered.

Franklin at Mainframe Studios.

“Remaining Reminders” evokes how the intimate items used on a daily basis—a comb, a pair of glasses, a keychain—can have a profound effect on the people left behind. Tucked inside the cabinet are handkerchiefs and notes in jars that Franklin wrote to imagine the secrets her father may have been hiding.