Writer: Christine Riccelli

Photographer: Paige Peterson

Stroll around the 17-acre grounds of Oakridge Neighborhood and whatever stereotype you may harbor about the former Homes of Oakridge, or of low-income housing in general, starts to dissipate.

In between the downtown complex’s 35 two-story apartment buildings, neatly kept green space holds swing sets and picnic tables. In front of one apartment, you’ll spot a small but thriving vegetable garden, while a few doors down a flower patch blooms. On the expansive main playground, enthusiastic day campers chase one another around. In an on-site center, adult residents attend classes on managing money while preschoolers learn the alphabet. And all around the complex, you see people representing cultures from far-flung corners of the globe.

What’s absent is that gut-nagging wariness about safety, an admittedly typical reaction among those whose only experience with low-income housing is through headlines focusing on crime or other problems.

Such misperceptions about the complex persist, says Teree Caldwell-Johnson, who has been CEO of Oakridge since 2004. “People think we’re one-dimensional, but that’s not the case,” she says. “We’re more than just housing; we seek to stabilize families as they pursue their life journey, with wraparound services that support residents from cradle through career.”

That’s the point Oakridge has been driving home for its 50th anniversary this year, when the complex, where about 1,200 people live in 300 Section 8 housing units, has been in the spotlight more than usual.

“Oakridge is rather unique,” says Eric Burmeister, executive director of the Polk County Housing Trust Fund. “Many of the developments that were built during that same period of time across the country have either closed or are no longer [rent-subsidized]. Fortunately, Oakridge not only is still there but has been kept in a condition that still benefits a lot of folks. … The community is fortunate to have Oakridge as one of the tools in its toolbox to address [the need for] affordable housing.”

Affordable Housing

Indeed, Oakridge also has been in the limelight as Greater Des Moines’ struggle to provide adequate affordable housing has drawn increasing attention over the past year among officials and community advocates (see story, page 164). Nearly one-third of Des Moines homeowners and renters are severely cost-burdened, meaning that they spend 30% or more of their income on housing, according an analysis released this summer by the Des Moines Municipal Housing Agency and by the cities of Des Moines and West Des Moines.

Polk, Dallas and Warren counties need nearly 12,000 more units of affordable housing than they have now, says Elisabeth Buck, president of United Way of Central Iowa. “When there’s a shortage of affordable options in a community, individuals are forced to spend more than they should on housing, and when that happens you see spikes in other services,” she says, noting that “we had a record number of food pantry users in the month of July. When you have to pay rent first, you don’t have enough money for food. Many of the needs are interconnected.”

Oakridge understands and addresses such interconnected needs. “Our shared vision with Oakridge is as a safe, affordable human services campus,” says Buck, adding that United Way helps fund seven programs at Oakridge, including the accredited Oak Academy and Project Oasis (see story, page 163). “We see Oakridge not only as an affordable place to live but also as a place for children to thrive and succeed. Our partnership with them focuses on education and financial stability. Our hope for residents is that they have the ability get out of poverty and … move from Oakridge to whatever the next phase of their lives is.”

Caldwell-Johnson says while some residents are longtime tenants, nearly 65% of families live at Oakridge for five years or less. But even though they move, some still return to Oakridge to participate in the various programs. Overall in 2018, the programs served a total of 512 children and 587 adults.

Steven Eggleston, Iowa’s field office director for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, says that while low-income housing properties in Iowa and across the country offer counseling and case management services to tenants, Oakridge’s programs are more comprehensive.

“Oakridge does a very good job” of serving tenants, he says.

“Their programs for children are especially [effective].”

New Iowans

Oakridge’s services have evolved as the neighborhood’s demographics have changed over the years. Today, some 60% of residents are refugees from about 24 countries, mostly from African nations (Nigeria, Sudan, Eritrea) but also from the Middle East (Iraq) and Asia (Vietnam).

“We’ve worked hard to build our staff portfolio to meet the needs of the people here,” Caldwell-Johnson says.

“We want to meet people where they are and in a way that recognizes and addresses the language and cultural barriers that limit them.”

Providing the educational, job training and other services costs about $3.5 million a year. Government funding covers about 40% of the cost, Caldwell-Johnson says, while the balance is raised through individuals, corporations and fundraising events, such as the annual Jazz, Jewels and Jeans, which this fall raised $175,000, up from 2018’s $144,246.

Safety First

Any success at Oakridge is predicated on residents of all ages feeling safe, and to that end, the organization has an on-site 24/7 security force. “Everyone wants to feel safe and secure; it’s a big factor in the overall quality of life,” Caldwell-Johnson says. “We’ve been very intentional about the importance of safety and security—it’s always front and center for us.”

Although security has always been a concern, and a priority, at Oakridge, it proved to be a daunting challenge in the late 1980s and the 1990s, when drugs and gang violence increased crime and threatened resident safety. People who didn’t live at Oakridge but who would nonetheless congregate there caused much of the trouble. Through a variety of measures—such as a stepped-up police presence and residents’ activism—the gang activity was addressed and eventually abated.

Sgt. Paul Parizek, public information officer for the Des Moines Police Department, says the police and Oakridge have had a “solid relationship” for decades.

“The most visible piece of that, for many years, was the presence of off-duty police officers at the complex, supplementing the Oakridge security staff,” he says. Oakridge also participates in the DMPD’s Crime Free Multi-Housing Program, which “provides comprehensive training to property owners [and] managers on strategies to maintain a safe housing environment for their residents.”

What’s more, Parizek says, “Oakridge hosts a vibrant collection of youth programs and neighborhood picnics in partnership with the police department. Keeping the residents engaged and invested in their neighborhood builds the sense of community, and that is the foundation that safety is built upon.

“In short, a universal proactive approach, rather than the ancient police model of being reactive, is what has made the difference in the neighborhood.”

In addition, residency rules have helped ensure security. Residents must have no drug offenses, no misdemeanor conviction in the past five years, and no felony conviction in the past 10 years.

Caldwell-Johnson says after a 13-month housing renovation in 2010—“we took everything down to the studs”—every resident had to reapply for their unit.

“We evaluated every applicant,” she says. “If there were any offenses that had accumulated during their time here, their leases were not renewed.”

The renovation and reevaluation process “was the best thing we ever did,” Caldwell-Johnson says. “We could refresh, recalibrate and rethink the next iteration of what our history should look like.”

‘Secret Sauce’

Oakridge typically has a six- to 24-month waiting list; currently 132 people are waiting for units. But while Oakridge officials and the board have considered the possibility of building additional housing to meet the growing need, they concluded it “isn’t doable,” Caldwell-Johnson says.

“Our secret sauce isn’t just the housing but the human services aspect, and replicating that combination would be very difficult,” she says.

Instead, the result of a strategic plan this year has Oakridge focusing on “maximizing what we’re doing the right way to benefit residents even more,” Caldwell-Johnson says. “This is our niche. There will always be an opportunity to innovate and create, to morph and enhance programs to further meet clients’ needs.”

No Place Like Home

Min Tran and Than Nguyen’s five adult children and eight grandchildren keep trying to persuade the couple to move to Houston, where they all live. But Tran, 77, and Nguyen, 68, who emigrated from Vietnam in 1991, quickly dismiss the notion. “Our children tell us they need to take care of us,” says Nguyen, explaining how she and her husband are battling various health issues. “But we want to stay here.”

Min Tran and Than Nguyen’s five adult children and eight grandchildren keep trying to persuade the couple to move to Houston, where they all live. But Tran, 77, and Nguyen, 68, who emigrated from Vietnam in 1991, quickly dismiss the notion. “Our children tell us they need to take care of us,” says Nguyen, explaining how she and her husband are battling various health issues. “But we want to stay here.”

When Tran and Nguyen moved to the United States, they settled at Oakridge with their four sons and one daughter, who at the time ranged in age from 5 to 18. Although they raised their family at a time when the complex experienced an uptick in crime, they say they never felt unsafe. Today, they’re glad to be close to their doctors at nearby Iowa Methodist Medical Center as well as to longtime Vietnamese friends at Oakridge who frequently visit their home.

Although the couple has returned to Vietnam four times since moving here, Nguyen says they’re always ready to come back to Oakridge: “This is home now.”

Community Support

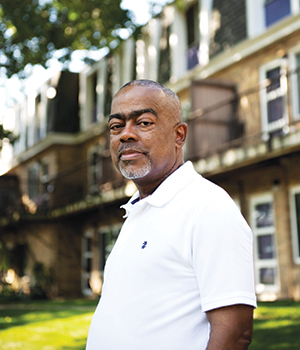

Glenn Singleton moved into a three-bedroom apartment in 1996 after gaining custody of his three children, who then were preschoolers. Oakridge was familiar to him; he was a full-time maintenance worker at the complex. The neighborhood “was the best affordable [option] for me,” says Singleton, a Des Moines native who grew up near Merle Hay Mall. “I was able to maintain my home and take care of my kids.”

Glenn Singleton moved into a three-bedroom apartment in 1996 after gaining custody of his three children, who then were preschoolers. Oakridge was familiar to him; he was a full-time maintenance worker at the complex. The neighborhood “was the best affordable [option] for me,” says Singleton, a Des Moines native who grew up near Merle Hay Mall. “I was able to maintain my home and take care of my kids.”

In addition to affordability, Oakridge offered day care and other support services and was convenient to the schools his children later attended, he says. “It got hard [being a single father] at times, but I had steady work and knew a lot of people here,” the now 60-year-old Singleton says. “I still know a lot of people.”

The changes at Oakridge over the past 20 years have been significant—and for the better, he says. “When I first started here, people who didn’t live here would come here and [cause] trouble,” Singleton says, adding that since then, more cameras, a stronger police presence and other measures have dramatically improved safety and security. “If it wouldn’t have improved, I would’ve been gone a long time ago,” he says. “It’s pretty peaceful here now.”

In addition, the renovation of the units in 2010 boosted the neighborhood’s livability, he says. “Before, there was no carpet, air conditioning or shower—now we have all that [plus] a washer and dryer and microwave,” he says.

Singleton also notes that the ample green space allows tenants to plant their own gardens or flowers. “Everything that’s been done has been helpful for the tenants,” he says.

Focused on the Future

While some tenants consider Oakridge a longtime home, Zahra Ismael and Mohammedsalih Mohammed see it as one stop on a journey that started when war forced them to leave their homeland of Eritrea in 2007. After living in an Ethiopian refugee camp, they moved to Baltimore and then West Des Moines before settling in Oakridge in 2013. The complex had more affordable rent than their apartment in West Des Moines and also provided a pathway toward their goal of homeownership, says the 30-year-old Ismael.

Specifically, she says, Oakridge offers programs on how to become a homeowner, covering such topics as managing money and understanding the American banking system. “Our plan is to buy a house for our family,” says Ismael, who works at Oakridge’s on-site day care center. She and Mohammed, who works at a home improvement store, have three daughters: Suad, 11, Iman, 8, and Safa, 3.

Although they are eager to buy a house and move from Oakridge, Ismael says she appreciates the neighborhood’s on-site preschool for Safa as well as the after-school programs for Iman and Suad. “They love their teachers here,” she says.

Citizen Pride

Walk into Moises Cano-Martinez’s apartment and his exuberance at being an American becomes instantly evident: A large American flag hangs from the living room ceiling, and a smaller one is displayed on the wall behind his couch. A photo of him at his citizenship ceremony hangs on another wall.

Walk into Moises Cano-Martinez’s apartment and his exuberance at being an American becomes instantly evident: A large American flag hangs from the living room ceiling, and a smaller one is displayed on the wall behind his couch. A photo of him at his citizenship ceremony hangs on another wall.

“I’m so proud of the day I [became] a U.S. citizen,” says the 55-year-old Guatemalan native, who fled his homeland about 30 years ago because of death threats. “When I was a kid, everyone would say, ‘Oh, the United States. I want to go there.’ ”

After immigrating, Cano-Martinez worked in the meatpacking industry in El Paso, Texas, and then in Perry, Iowa. When he moved to Des Moines in 2004, “people would say that [Oakridge] was a terrible place, but I’ve had no trouble here,” he says. “There are many African [immigrants] here, and I’ve made friends with them.”

Cano-Martinez’s 78-year-old mother lives in the unit next door, and he has no plans to move elsewhere. He points to the apartment’s washer and dryer and other mod cons. “I have everything I need here,” he says.

American Dream

When we caught up with Taggu Afaray at Oakridge, she was in the midst of a typical industrious day. Afaray, who has lived at Oak Ridge since 2016, has a full-time job, attends classes at Des Moines Area Community College, and is working toward completing 400 hours of sweat equity for a new Habitat for Humanity home that, at press time, she was expecting to move into in late fall.

When we caught up with Taggu Afaray at Oakridge, she was in the midst of a typical industrious day. Afaray, who has lived at Oak Ridge since 2016, has a full-time job, attends classes at Des Moines Area Community College, and is working toward completing 400 hours of sweat equity for a new Habitat for Humanity home that, at press time, she was expecting to move into in late fall.

With her hectic schedule, Afaray, 31, is grateful that her mother lives at Oakridge, too, and can help care for her sons—5-year-old Martin and 13-year-old Samuel—when she works. Her sister and six brothers also all live in Des Moines, providing additional support. Natives of Eritrea, the family escaped to a refugee camp in Ethiopia after Afaray’s father was killed in the Eritrean-Ethiopian conflict that raged between the two Horn of Africa nations for 20 years (a peace agreement was signed in 2018). The family lived in the camp for seven years, “where there was never enough food or clothing,” Afaray recalls.

Upon immigrating in 2007, Afaray moved to Chicago and then, in 2014, to Des Moines. At Oakridge, she says she received help studying for her citizenship test through classes, books and CDs that she otherwise wouldn’t have had such easy access to. She became a citizen in 2018 and says she remains hopeful for the future: “I’m very excited for our new [Habitat] home.”

Oakridge Neighborhood at a Glance

The campus is located on 17 acres just north and west of downtown, at 15th and Center streets.

About 1,200 residents live in 300 low-income housing units.

An additional 40 people age 55 and older live in the adjacent Silver Oaks apartment building, located just north of the main campus. Opened in 2013, Silver Oaks offers 39 affordable one- and two-bedroom units. All units are market rate, although Section 8 vouchers are accepted.

99% of residents are low-income, including those at Silver Oaks.

60% of residents are refugees from about 24 countries.

51% of residents are under age 18.

78% of households are led by a single parent with an average annual income of $10,656. The average income for all other households is $18,608.

70 full- and part-time people are employed at Oakridge.

Oakridge contracts with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to administer the Project-Based Section 8 housing program. Unlike the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher program, Oakridge rent subsidies are assigned to the unit and not the individual. Under the Project-Based program, when tenants move out, they no longer have rental assistance. Depending on their income and family size, tenants pay a maximum of 30% of their income to Oakridge, and HUD pays Oakridge the balance of the market rate.

Some of the Services Offered at Oakridge

Oakridge Neighborhood Services is the organization’s human services agency that provides a variety of support programs for residents and is funded by government grants and corporate and individual donations. Major programs include the following:

Transitions: Program for refugees that includes English and citizenship classes, driver education, job-seeking services, case management and more. In 2018, 105 participants were placed in jobs and 39 people completed the English language course.

Oak Academy: State-certified early-enrichment program that encompasses both child care and preschool.

Project Oasis: An after-school program that helps students from kindergarten through fifth grade increase reading and math proficiency and also improve attendance and behavior. In 2018, 93% of participating students were satisfactory in reading, 89% in math and 99% in science.

Be Real Academy: Comprehensive program that helps young teens and their parents understand and prepare for middle school. Offers academic support, sports teams, field trips, mentoring and counseling. In 2018, 98% of participating students passed language arts, 99% math and 91% science.

Youth Summer Employment Program: Provides employment training and opportunities for high school students.

Need for Affordable Housing Continues to Grow

Des Moines currently offers 3,173 Section 8 housing choice vouchers, according to the Des Moines Municipal Housing Agency, and, as of press time, the waitlist was closed. The average voucher household in Des Moines has an income of just $12,456 per year.

But the need for affordable housing extends beyond those at the lowest rung of the economic ladder, local housing experts agree.

“Our housing struggles are moving higher up the ladder,” says Eric Burmeister, executive director of the Polk County Housing Trust Fund. “There are a lot of people at all different income levels who are simply unable to afford market-rate housing.”

This is largely because housing costs have risen much more rapidly than wages, so “we have folks who are becoming cost-burdened who weren’t before,” Burmeister says, adding that the cost of homes and apartments is beyond the budget of people who, for instance, work full time in the service industry and in other positions that play a vital role in the community.

For example, the average annual salary of a teacher’s assistant is $22,180 and a grocer is $23,670. Housing is considered unaffordable if the cost is 30% or more of the household’s income. So that teacher assistant’s monthly mortgage or rent and utilities shouldn’t exceed $554.50 a month.

The disparity between income and housing costs is getting so severe that “every day that goes by, we’re digging a bigger hole as a community,” Burmeister says. “We need to figure out policy changes to stop this progression … [or] we’ll start to look like places we never thought we’d look like, [such as]

San Francisco or Boston.”

Burmeister and other housing experts agree that affordable housing is connected with a host of other issues, including transportation, health, education and workforce participation. Affordable housing “is a big issue that takes a lot of players looking at it broadly … across many systems,” such as the mental health, criminal justice and education systems, says Elisabeth Buck, president of United Way of Central Iowa.

“The good news is that we are a collaborative community,” she says, noting the work of the Polk County Continuum of Care (PCCoC), which consists of a variety of government agencies, businesses, schools, the police department and nonprofit and faith-based organizations.

In July, the PCCoC issued a report on strategies to address homelessness. “We’re starting to look at data and develop a comprehensive plan,” Buck says. “There’s reason for hope.”