Above: Students from all Des Moines high schools—a minority-majority district—and other Central Iowa schools connect at the Youth Diversity & Inclusion Summit. Photography courtesy of Des Moines Public Schools

Writer: Dawn Sagario Pauls

Candid conversations, real solutions.

That’s what students who’ve participated in the annual Youth Diversity & Inclusion Summit say they’ve experienced. Sponsored by Des Moines Public Schools (DMPS) and Wellmark Blue Cross and Blue Shield, the one-day convention seeks to help students share their voices, understand differences and build relationships. The third summit, held last November, drew 250 students from 15 Central Iowa high schools to Wellmark’s downtown Des Moines campus to explore such topics as acceptance and openness.

Students take what they’ve learned back to their schools, spurring conversations and action among their peers and administrators to promote inclusion and diversity.

“Every person walks away with a sense of drive and renewed perspective,” says Fez Zafar, 18, a Pakistani American who this spring graduated from Roosevelt High School.

The summit was created in 2017 following an incident during which a racial slur was used on the football field between a DMPS team and a suburban team. It has grown every year since, and in 2019, the focus shifted more to inclusion instead of the earlier emphasis on diversity and race. Students also had more time to meet with their peers.

“The true intent of the summit [is] to give [students] the chance to learn from each other,” says Cory Jackson, a health management consultant with Wellmark. Jackson, a DMPS parent, approached Wellmark about partnering with DMPS on the event.

“Inspiring the next generation of student leaders to understand the importance of diversity and inclusion is one of the best investments Wellmark can make in our community,” says John Forsyth, Wellmark’s chairman and CEO, adding that the company embraces having a role “in connecting diverse students with the opportunity to be heard and inspire one another.”

During the breakout sessions at the 2019 event, participants from Southeast Polk created a professional development seminar for teachers, covering such topics as perspective, climate and culture; micro aggressions; and making classrooms culturally inclusive, says Patrick Tunks, who will be a senior at the school this fall.

As a result of the summit, the Southeast Polk district plans to lead professional development seminars at Spring Creek 6th Grade Center and Southeast Polk Junior High School, he says. They’re also planning to make a presentation to the school board and to Southeast Polk High School students enrolled in Des Moines Area Community College’s Teacher Academy program.

Tunks has attended the summit twice. Listening to how other teens are working toward fostering greater inclusivity has motivated him to do more in his daily life, he says: “It’s really about starting a conversation.” For example, in the hallways at his school, he now says hi to many more people, taking the initiative to reach out and “make them feel valued.”

Roosevelt High School is one of Iowa’s most diverse schools, says Zafar, who was student body president this past school year. But when he arrived there, one of the things he noticed was how students of different races and ethnicities grouped together during lunch.

“Most schools tend to sweep these issues under the rug,” Zafar says. “I feel our administration’s effort to build equity and improve the culture in our building shows the impact that the summit has had on our school alone.”

To ensure that minority voices are heard, Roosevelt Principal Kevin Biggs created a diversity and inclusion council. Members share their experiences, thoughts on school culture, and the steps they believe should be taken to enhance greater understanding.

“It’s these kinds of strategies that my school has been implementing that have worked for the better,” Zafar says.

“The theme here,” he adds, “is listening and one-on-one engagement.”

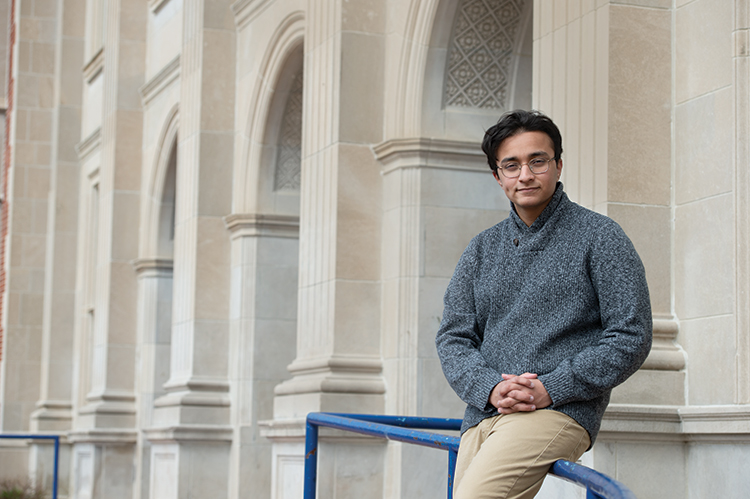

Roosevelt High School graduate and 2019-2020 student body president, Fez Zafar, has been<br />

a leader in his school’s inclusion efforts. Photographer: Duane Tinkey

|

Building Urban Leadership Students in a Central Campus class are becoming community-based activists as they study hip-hop culture and learn about social movements shaping cities today. The Urban Leadership program, which just completed its seventh year, engages 10th- through 12th-graders with a focus on community and outreach. “We wanted to create a space where young people could feel empowered to talk about their experiences with marginalization and oppression,” says teacher Emily Lang. The two-year program involves over 100 students annually. Textbooks aren’t part of the curriculum, but the classroom walls speak with images, poems, memes and more, covering topics such as LGBTQ rights and Black Lives Matter. “We use students’ stories and experiences to move us to a better place of understanding,” Lang says. Youths are given opportunities to lead through writing, speaking, urban arts, internships, and community summits. “They’re already leaders,” Lang says. “They just need platforms and opportunities to utilize that leadership, express that leadership and practice leadership.” The annual two-day Teen Summit also is part of the Urban Leadership program. The goal is to help teens create safe spaces where they can delve into issues they face and come up with possible solutions. For the 2020 summit held last February, for instance, the Urban Leadership students explored such topics as eliminating toxic behaviors, LGBTQ identity, and Latinx history and rights. The summit also includes a community showcase, open to the public, that features a gallery of visual art as well a variety of student performances, such as hip-hop dance, ballet and spoken word poetry. |

Connecting Through Sports

Throughout Iowa, Special Olympians and their peers without intellectual disabilities are playing hoops and tossing bocce balls while building friendships.

Throughout Iowa, Special Olympians and their peers without intellectual disabilities are playing hoops and tossing bocce balls while building friendships.

Through the Special Olympics Unified Sports programs, athletes play alongside one another on teams of similar age and ability. “We’re using sports as the catalyst to help encourage friendships of all abilities,” says Bryan Coffey, director of Unified Programs for Special Olympics Iowa.

Statewide, about 600 special-education students engage with 600 general-education kids, he says. In the metro area, 37 schools participate.

This year, Des Moines Public Schools wrapped up its first season of Unified Sports at a competitive level, with high school and middle school students playing basketball. An adaptive hoop hangs below the net for students in wheelchairs.

“We’re seeing greater impact and more long-lasting friendships created through team sports,” Coffey says.