As part of his “Harvesting Humanity” project, Robert Moore embraced the Black Lives Matter movement by displaying images of George Floyd, Rosa Parks and Malcolm X on Dallas County grain silos. Photographer: Jami Milne.

Writer: Brianne Sanchez

The paint Robert Moore mixes on his hand is shades darker than his own brown skin. Pigments of umber and black might fill in the portrait of a little girl in braids, or outline iconography inspired by spirituality and his mother’s addiction to crack cocaine. With himself as the palette, each brushstroke brings out more of Moore.

The desire to know himself as a biracial Black man and survivor of trauma, combined with his commitment to sobriety, has fueled a period of prolific creativity for Moore, 36, a self-taught artist and entrepreneur.

“It’s a counter to addiction,” Moore says. “I was very much committed to drinking and using every day. Now I just do it with art.”

Before the pandemic hit, Moore estimates he had already completed 100 pieces, and he is on track to triple that number by the end of the year. Working quickly is a catharsis, and it allows him to capitalize on some of the commercial attention he’s been receiving for his work during the Black Lives Matter movement.

“I’m learning every time I paint a new painting,” Moore says. “But I don’t want to be boxed in. I’m almost a habitual line-toer in a sense. I am almost resistant to traditional confines or restrictions. … I want to contrast what is normal and what is my experience, in a very vulnerable tone—to heal.”

Robert Moore in his basement studio. Find information about his work, including original paintings and prints for sale, on his website. Photographer: Duane Tinkey

Robert Moore in his basement studio. Find information about his work, including original paintings and prints for sale, on his website. Photographer: Duane Tinkey

Projections and Murals

Moore’s style favors layers over details and is reminiscent of Jean-Michel Basquiat, yet he embraces a range. Moore is continually exploring with different types of art—abstracts, cartoons, collages, portraiture. Recently, that’s meant experimenting with projected images and mural installations.

For a project on the new Market House building in Iowa City, Moore and artistic collaborator Dana Harrison sought to elevate marginalized voices with a mural of a pair of Sudanese and Ethiopian women flanked by hovering goldfinches. In “Harvesting Humanity,” ephemeral images of George Floyd, Malcolm X, Rosa Parks and local youths were projected onto grain silos in Dallas County. The projects are examples of how Moore uses a variety of mediums to promote social justice.

“I saw different people responding to police brutality,” Moore says. “I love the protesting, but I saw how that was being received in rural America and thought I would really like to do a silent protest.”

With location scouting help from his uncle and assistance from photographers Paige Peterson Connelly and Jami Milne, Moore pulled the project together in just four days. That concept was also the inspiration for “Projecting Pride,” a collaboration with One Iowa that in June commemorated the 51st anniversary of the Stonewall Riots. For that project, multistory portraits of local LGBTQ leaders and national icons, such as Marsha P. Johnson, were illuminated in downtown Des Moines.

“It was bittersweet to hear, ‘God, I wish I didn’t have to be projected 80 feet tall to be seen,’ ” Courtney Reyes, executive director of One Iowa, says of the impact of the piece.

“Projecting Pride” displayed portraits of local and national LGBTQ leaders in downtown Des Moines this past June. Photographer: Jami Milne

“Projecting Pride” displayed portraits of local and national LGBTQ leaders in downtown Des Moines this past June. Photographer: Jami Milne

Diversifying Peanuts

“Uplift,” at the corner of Euclid and Second avenues, features a group of reimagined Peanuts characters—Black kids to reflect the diverse Highland Park neighborhood where Moore lived through middle school. He attended Findley Elementary and Harding Middle schools before moving to Johnston for high school.

“Growing up, I never felt like I was an artist,” Moore says.

He joined the National Guard at 17 and moved to Iowa City, where he worked in telecommunications and got into partying, drug addiction and dealing. A felony charge for his involvement in a marijuana farm was a low point for Moore, who was facing prison time just as he was about to become a father.

The charge has since been expunged, but Moore is clear that it wasn’t the “good trouble” civil rights leader John Lewis encouraged that motivated him at that time. A portrait of the late U.S. representative that Moore painted in tribute within days his death is striking, with the subject gazing straight ahead.

The confidence conveyed through the piece was hard-earned by Moore, who started painting much more abstractly in 2014. His first portrait (of President Barack Obama) was painted with a butter knife. He hones his techniques as he works through trauma and took on an internal challenge to paint with more realism.

“I obsess over things I don’t like to do and I want to be better at it,” Moore says. “I didn’t really care about the subject of faces I painted as much until I had my DNA test last year. Being Black is a beautiful thing. There’s richness, there’s culture, there’s absolutely no shame. … When you can identify and have pride in saying my genetics are from this country (Nigeria, Cameroon, Benin-Togo and Senegal in Moore’s case), it was an explosion.”

Pushing Boundaries

Moore’s portraits also caught the eye of Jeff Fleming, director of the Des Moines Art Center, during a studio visit leading up to the Art Center’s current “Black Stories” exhibit, on display through January. Moore is serving on the advisory committee related to the exhibition, which was co-curated by acclaimed local artists Jordan Weber and Mitchell Squire.

“It truly was one of the best studio visits I’ve ever had,” Fleming says. Moore “is a very young artist and he will freely share that. … But there is an intensity and integrity of his work that is very rare. He’s always pushing the boundaries. He’s not encumbered with ‘This is where I’m supposed to be.’ It’s really quite refreshing.”

For those who have known him since his partying days, this new portrait of Moore seems rendered with much more clarity.

“It has been such a beautiful thing watching him find his voice in his art,” says Jamie Nicolino, who first met Moore in about 2005 and ran in the same Iowa City circle. “He’s found himself. He stands very differently now. He’s a person you want to know because he’s not afraid of being who he is.”

Nicolino, who now owns the Collective, a sustainable supply company on Southwest Fifth Street in Des Moines, says the journeys of sobriety and entrepreneurship she shares with Moore rekindled their friendship.

“The political climate and the social justice climate [are] only going to further inspire and awaken him as an artist,” she says. “It’s raw and it’s real. He’s not hiding anything. I don’t feel like he will ever let anyone tell him who or what to be.”

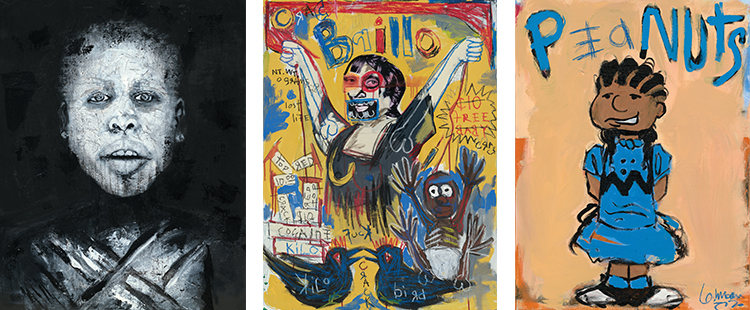

From left: “Karo Boy” was inspired by Moore’s favorite photographer of indigenous people. “Brillo” represents “Mommy Lady Justice,” Moore says. “Lucy” is part of the “Brown Like Me P-nut” series, which recreates popular figures including Charlie Brown and Linus van Pelt in brown skin tones.

Instagram Attention

Moore’s work is garnering national attention from followers through his Instagram, where he posts works in progress, often with extended captions that provide a written narrative behind the pieces, as well as art for sale and images from collectors who have installed pieces. Occasionally, he’ll also stream his painting process on the site.