Writer: Kellye Crocker

When a Des Moines counselor diagnosed me with anxiety in the late 1990s, the only surprise was that it was a thing. I was born worried. Anxiety felt like oxygen. When I left my first newspaper reporting job in Arizona to return to Iowa where I’d grown up, my co-workers gave me a caricature drawn by the editorial cartoonist. The speech bubble above my head said, “I’m freaking out!”

I’d been back in Iowa for 26 years—and thought I’d die happy there—when my husband’s West Des Moines-based architecture firm offered him a job at its newly reopened Denver office.

Colorado was beautiful, exciting and different. But the move caused my anxiety—fairly controlled for years—to soar higher than the state’s famous mountains.

At the same time, I felt down about my writing. Years earlier, I’d taken out student loans to study fiction-writing for young people—my longtime dream. I’d written fiction seriously since earning my MFA in 2006, yet I remained unpublished. To break my funk, a friend encouraged me to play on the page.

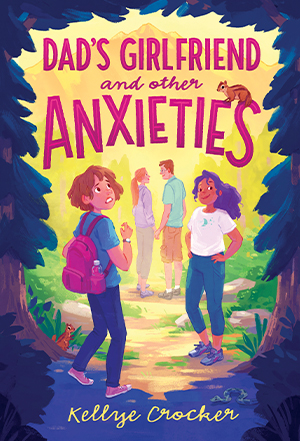

It was great fun exploring the state with my new protagonist, 12-year-old Ava, who’s forced to visit Colorado to meet her dad’s girlfriend and her daughter. That story became “Dad’s Girlfriend and Other Anxieties,” my debut novel for middle-grade readers—roughly ages 9-12—which was published in November.

Although recently diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, Ava is happy in her small Iowa town surrounded by extended family and lifelong friends. She’s not used to meeting people and has no interest in Colorado, especially after researching the state’s many dangers, including wildfires, charging elk and altitude sickness. (“The air can kill you, Dad.”) The scariest thing, though, may be The Girlfriend, who happens to be awesome. How serious is their relationship, and what does that mean for Ava?

Although recently diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, Ava is happy in her small Iowa town surrounded by extended family and lifelong friends. She’s not used to meeting people and has no interest in Colorado, especially after researching the state’s many dangers, including wildfires, charging elk and altitude sickness. (“The air can kill you, Dad.”) The scariest thing, though, may be The Girlfriend, who happens to be awesome. How serious is their relationship, and what does that mean for Ava?

I didn’t intend to write about anxiety. But this is how it works: Stuff shows up—images, scraps of dialogue, a metaphor, whatever. They feel inconsequential, merely supporting details in The Big Story I’m Writing, until I see them. Really see them, I mean, and their connections. It’s one of the sweetest, most magical elements of creating fiction. That’s when the real story opens, the one I have far less control over than I’d like to imagine.

Embracing Humor

Writing this story also unexpectedly helped me cope with my own anxiety—by laughing at it. Please don’t misunderstand. Anxiety is no joke. For me, the physical experience ranges from uncomfortable to agonizing. The symptoms—such as nausea, a racing heart, dizziness, sweating, numbness and tingling, difficulty breathing, and the dreaded FID (Fear of Impending Doom)—can appear without warning and for no apparent reason.

When I’m able to step back and observe my worries, though, they’re often funny. I have a “glass half empty” default and work hard to remember it’s also half full. But I can’t help wondering: Is there more? How long can someone go without water? It’s a paradox that I can feel anxious yet also know I’m fine. Probably.

Gaining perspective and realizing my racing thoughts are separate from me are skills I learned in therapy. In the years since my diagnosis, I’ve dipped in and out and wouldn’t hesitate to return if needed. I’m deeply grateful to the mental health professionals who gave me tools that improved my life. (I’ve seen a couple of counselors who were a bad fit. I encourage people who have that experience to try someone else. Don’t give up on counseling itself.)

Ava isn’t wrong about Colorado’s dangers—but she can’t put them into perspective. As a smart kid, she’s aware of risk assessment, but her fears and prejudices easily overwhelm logic, such as when she tells her dad that Colorado’s cute little ground squirrels can spread plague through bites. “You have a fifty-fifty chance of dying. Well, if you don’t go to the doctor—but, still.”

Like everyone else, I fell in love with Colorado. Ava’s contrarian view—It wasn’t Ava’s fault the state was so terrible—tickled me. Exaggeration can create humor, and humor is critical in stories that dive into the heart’s tenderest places. Humor is a light in the dark. Laughter is hope.

Like any good protagonist, Ava changes during the story. I wanted to show that shy, quiet, anxious girls can be strong, too, and that there isn’t only one way to be brave.

Reframing Anxious Feelings

Of course, we all feel anxious sometimes. (Especially these past few years.) And anxiety can be helpful. It’s how our body alerts us to danger. One bit of popular advice is to reframe anxious feelings as excitement. Those of us with anxiety disorders, though, experience these feelings more often and more intensely, to a degree that interferes with day-to-day life over an extended period. In my novel, Ava compares her anxiety to having a faulty internal smoke detector. It sounds an alarm even when there’s no smoke or fire.

When I finished the first draft in 2016, mental health professionals were already concerned about anxiety in children and teens. The situation has worsened. Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental illness among Americans—young and old, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness. As a society, we must do more, especially for our young people and those in marginalized communities who already face higher stress from discrimination, limited access to health care and other obstacles.

I’m grateful that young people and medical folks are talking about mental health. I don’t remember anyone talking seriously about it in the 1990s. I felt ashamed of my diagnosis and kept it secret. I wish I’d known I wasn’t alone.

When I told an older relative that the protagonist in my book has an anxiety disorder, he shook his head dismissively and said everyone needs a label these days. We still have a ways to go to remove the stigma from mental illness. But it feels as if we’re making progress.

I tend to my mental health daily. Since my diagnosis, I’ve taken anxiety medication, although the kind, dosage and effects have varied. Journaling, yoga, meditation, deep breathing and painting are part of my feel-good, mindfulness routines. (Though not all at once!) I also limit caffeine and prioritize sleep. Getting off my phone and out into nature does me a world of good, but I don’t do it often enough.

Publishing this novel is a lifelong dream but it’s also brought—wait for it—anxiety. I probably shouldn’t have been surprised. Fiction-writing feels much more personal than the journalism I’ve written most of my adult life. The good news is that through this experience, I’m learning more about vulnerability. That will only make my next book better.

Kellye Crocker’s new book, “Dad’s Girlfriend and Other Anxieties” from Whitman, Albert & Company, is available now through online retailers. Crocker currently lives in Denver

Among U.S. Adolescents (ages 12-17) in 2020

1 in 6 experienced a major depressive episode.

3 million had serious thoughts of suicide.

1 in 10 experienced a mental health condition after a COVID-19 diagnosis.

31% increase in mental health-related emergency department visits.

Percentage of People Receiving Treatment in a Given Year

51% of young people (ages 6-17) with a mental health condition.

45% of adults with mental illness.

66% of adults with serious mental illness.

Among U.S. Young Adults (ages 18-25) in 2020

1 in 3 experienced a mental illness.

1 in 10 experienced a serious mental illness.

3.8 million had serious thoughts of suicide.

Source: National Alliance on Mental Illness