Photos by Duane Tinkey

Take a look around Greater Des Moines and you see the influence of the women and men dsm is honoring as this year’s Sages Over 70. Through their progressive work in business, government, law and the nonprofit sector, they’ve made the city better for all residents, whether by guiding school integration efforts, breaking down gender barriers or ensuring adequate housing for those with disabilities. Their dedication to the metro area is also evident in downtown’s renaissance and the blossoming of the arts and cultural scene, as well as through the countless charitable organizations they’ve supported, often behind the scenes. Perhaps most important, the Sages have mentored others over the decades, ensuring that their legacy of giving will continue to shape the city.

Please join us in congratulating these distinguished women and men at a special event 5–7 p.m. Nov. 14 at the World Food Prize Hall of Laureates. The cost is $50, or $25 for young professionals (tickets are available by clicking here). Proceeds will benefit the Sages Over 70 Fund at the Community Foundation of Greater Des Moines, our presenting partner.

In the stories below, this year’s Sages share their views of the city, their hard-won lessons, their hopes. Also, be sure to view the videos of each Sage by clicking here; you’ll no doubt be amused by their sense of humor, inspired by their experiences and enlightened by their wisdom.

Richard “Red” Brannan

Richard “Red” Brannan

Written by Kyle Oppenhuizen

Richard “Red” Brannan spent more than 20 years on the Polk County Board of Supervisors and also 17 years at the Des Moines Development Corp., one of three organizations that merged in 1999 to become the Greater Des Moines Partnership.

Now 76, Brannan is mostly retired, though he still does some consulting work on development projects as a “go-between” person between companies and the public sector. Prior to retirement, he worked with Fred Weitz, who ran The Weitz Co., and former Des Moines City Manager Richard Wilkey to make Prairie Meadows Racetrack and Casino a reality. Under his leadership, Des Moines Development grew from 17 members to 80. As a private consultant, he helped jump-start the redevelopment of the Western Gateway area and the East Village.

Brannan, a Coon Rapids native who spent three years in the U.S. Army after high school, was elected to the board of supervisors in 1969 after working at Deere & Co. for about 10 years and becoming active in the United Auto Workers union. Throughout his career, Brannan’s passions were helping developmentally disabled people, being a mentor and coordinating efforts to develop downtown.

“Red has always had a really creative mind around community growth and that sort of civic planning and engagement,” says Martha Willits, former president and CEO of the Greater Des Moines Partnership. She adds that he was one of the first community leaders to focus on regional thinking: “Red really understood the economy, the economies of communities working together (and) of development for business attraction … and improving the quality of life. He was ahead of the game in terms of an elected official in that regard.”

Unlike many of the city’s corporate and philanthropic leaders, Brannan came from a modest background. He didn’t attend college and gained a reputation for being fearless about sharing his opinion. Today, he lives in Ankeny with his wife, Kay. They have three grown children.

Proudest accomplishment

When Brannan was on the Polk County Board of Supervisors in the early 1980s, he helped set up a number of homes, scattered in different metro-area neighborhoods, that provided services for developmentally disabled people. Residents were able to live a life “much more close to what the average person was doing,” Brannan says.

Most significant memory

“Winning my first election on the county board would have been one,” says Brannan, who served on the board until 1991. Another was having his German wirehaired pointer place second in its breed at the Westminster Dog Show in 2010.

Untapped advice

“Don’t worry about limitations,” Brannan says. “If you think there’s something you want to do, go ahead and do it. Take your best shot. See if you can get it done.”

Most significant thing to happen in Greater Des Moines

“Downtown redevelopment,” Brannan says. “It didn’t happen haphazardly. It was basically planned out.”

Being a mentor

“I think it’s something that just happened,” he says. Over the years, Brannan has mentored many people, sometimes talking them into applying for a position. When Martha Willits was on the Polk County Board of Supervisors, he advised her to apply for the soon-to-be-open top position at United Way of Central Iowa. She didn’t get the job, but a few years later, he persuaded her to apply again, saying, “This time I’m going to lay you a road map. This is who you should talk to.” That time, she got the job. Brannan also talked Angela Connolly into running for the county board. “She knew I was up to something” when he called her to get a cup of coffee, he says. She took his advice, and won the race.

In retirement

Brannan is a fisherman and an avid hunter, with a particular interest in German wirehaired dogs. He also enjoys following his grandchildren’s various activities and hasn’t missed an Ankeny High School football game within driving distance for 20 years.

Johnny Danos

Johnny Danos

Written by Kyle Oppenhuizen

Johnny Danos worked for 33 years as a certified public accountant and managing partner at KPMG (formerly Peat Marwick), but it was his second career as president of the Community Foundation of Greater Des Moines where he says he did his best work.

Danos, 72, became president of the foundation in 1999. In his 10 years at the helm, the foundation’s assets grew from less than $20 million to $180 million. He increased the foundation’s staff, as well as its recognition and presence in Greater Des Moines. Still a member of the board, he considers the foundation’s role as critical in leading or helping with philanthropic projects.

A New Orleans native, Danos served in the U.S. Army during the Berlin Crisis of 1961. He also spent time in Baton Rouge, La., and Brussels before settling in Des Moines in 1978.

“Johnny has been a visionary leader in Des Moines,” says Kristi Knous, president and chief operating officer of the Community Foundation. “He has helped this community focus on the importance of giving back … and working together (to address) issues that are important for the future of Des Moines.

“He really grew this Community Foundation into what it has become, or at least set the platform for that growth to happen,” she adds. “He took a lead in helping us see the importance of building long-term resources for this community.”

Danos now works part time as the director of strategic development at LWBJ Financial LLC. A longtime foodie, Danos enjoys cooking specialties from his native Louisiana, and he and his wife, Theresa Van Vleet-Danos, are known for hosting dinner parties that benefit local charities.

Success

Danos considers increasing the reach of the Community Foundation his biggest accomplishment. When he stepped in to lead the organization, his vision was for it to be more than a charitable bank. It had the opportunity, he says, to build a staff to work with donors and collaborate on something bigger than the donors’ dollars by themselves could create.

In addition, the foundation has played a role in taking the lead on projects, Danos says. “The big projects know they need more money than (the foundation) can afford to put in it, but they very much want our endorsement of the project,” he says. “I think that’s an indication that we’ve become an important factor in community development.”

He also pushed the Iowa Legislature to pass the Endow Iowa Tax Credit, in which donors who contribute to a permanently endowed fund at a qualified community foundation can receive a 25 percent state tax credit, along with federal deductions. Since its creation in 2003, the program has generated more than $100 million in donations to Iowa’s 130 community foundations.

Biggest challenge

Besides getting his golf handicap down, Danos says trying to get recognized early in his career at KPMG proved challenging. He was never at the “top of the class,” he says, so advancing took doing the things that nobody else was willing to do, whether transferring to other cities or departments, making speeches or just being the all-around “good servant,” he says. “I did it by being the person they could count on to do the jobs that nobody else wanted to do.”

Most significant thing to happen to Des Moines

In the past, three or four well-known philanthropists drove community projects, Danos says. Now a network of people and businesses take turns leading projects as well as mentoring the next generation of leaders.

Untapped advice

“I think that you simply have got to listen to what people have to say, what they are not being allowed to say,” he says. “You’ve got to find ways to elicit a person’s real thoughts. Very often in meetings, you ought to be listening to the dog that isn’t barking.”

Nolden Gentry

Nolden Gentry

Written by Jane Schorer Meisner

Given his 6-foot-7 height, people might assume that Des Moines attorney Nolden Gentry played basketball—and they would be right. Gentry, a member of the Illinois High School Basketball Hall of Fame, also starred with the University of Iowa Hawkeyes before pursuing a legal career.

He moved to the South Side of Des Moines in 1965 to serve as an assistant attorney general and two years later became a founding partner of what today is the Brick Gentry law firm. He’s served on numerous boards of directors, including Bankers Trust Co., the University of Iowa Foundation, Drake Relays and the Civic Center of Greater Des Moines.

Gentry, who was inducted in 2007 into the Iowa African-American Hall of Fame, was the first African-American to serve on the Des Moines Board of Education. Despite the unpopular position of the school board in advancing desegregation in Des Moines, Gentry managed to bring people together who held different views, says Jacquie Easley McGhee, director of community and diversity services at Mercy Medical Center.

“I believe his example of a calm, poised manner in those times of fury paved the way for an impactful discussion in Des Moines on equal housing and employment,” she says.

Gentry, 75, is married to Barbara Gentry, whom he met at the University of Iowa when she was studying to become a physical therapist. They have three children and two grandchildren.

Mentor

When Gentry was about to enter Rockford West High School, in his hometown of Rockford, Ill., he showed his minister the schedule of classes he had chosen. The minister promptly tore it up, insisting that Gentry take college prep classes instead of less challenging courses—even though college was not on Gentry’s radar.

“There were not many professional African-Americans in Rockford; most of the people who I grew up with just went to work in one of the factories,” Gentry says. But because of the minister’s influence, Gentry took classes that prepared him to later be considered by colleges.

His minister’s example has stuck with Gentry. “There are people who have given time and attention to me, and I feel that it’s incumbent on me to do the same for people who follow,” he says.

Proudest accomplishment

Gentry says his most meaningful contribution came as a member of the board of directors of Delta Dental Corp. Beginning when it was newly incorporated, he worked with the company for about 30 years. Today, Delta Dental is the largest dental insurance company in Iowa, Gentry says. It has donated millions of dollars to dental colleges, and it provides tuition reimbursement for dentists who agree to practice in an underserved area in Iowa for three years.

The future of Des Moines

The city needs to continue to develop programs and projects as it has the past 10 years, Gentry says, such as the John and Mary Pappajohn Sculpture Park, the World Food Prize Hall of Laureates, the East Village and the Principal Riverwalk.

The next leaders

Gentry expects the Greater Des Moines Partnership to play a major role in future progress in Des Moines. But he also believes that the next generation of familiar names—Krause, Cownie, Ruan—will emerge to become civic leaders. “There is something about Des Moines that causes people to step forward,” he says.

Untapped advice

“We need to continue to find ways as a metropolitan area to work together,” Gentry says. “It would be beneficial for all of the municipalities if we could expand those things that we can do jointly.”

For example, if Des Moines leaders decide to put in a bid to host the 2016 Olympic trials, it would be a “major, major project of the Greater Des Moines area,” Gentry says. “There would be probably 10,000 athletes who would be here for at least a week, and it would really provide an opportunity for us to showcase our community.”

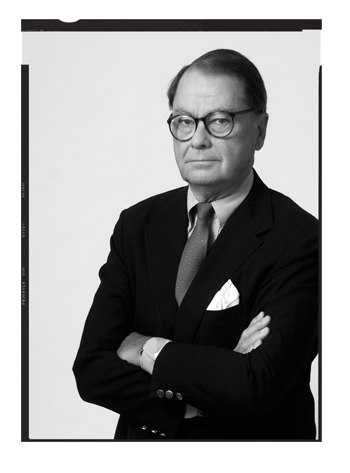

David Hurd

David Hurd

Written by Chelsea Keenan

For G. David Hurd, 83, a temporary job at Principal Financial Group Inc. turned into a 40-year career. After serving in the Korean War, he joined the then-Bankers Life Co. to save enough money to start his own business, but soon that idea began to fade. After 27 years with the company, he was named president in 1987 and was elected chairman and CEO two years later.

“Under Dave’s leadership, The Principal developed into a different company,” Mary O’Keefe, senior vice president and chief marketing officer at Principal, said in nominating Hurd. Praising his “integrity, passion, intelligence and humor,” O’Keefe added that during Hurd’s tenure, “the company’s assets more than doubled. But Dave’s legacy goes far beyond the bottom line numbers. Dave had a remarkable vision for where the company needed to grow.”

A committed family man, Hurd took care of his first two wives during their battles with chronic illnesses. “Dave’s commitment to his vows, in sickness and in health, was inspirational,” O’Keefe noted.

Hurd has three grown children and married his third wife, Trudy, in August. The two enjoy collecting art and traveling. Hurd has been around the world, traveling to Asia and much of Europe, with Paris being his favorite spot. But now, he and his wife plan to visit several national parks and keep their travel plans domestic, he says.

Key to success

Modestly, Hurd says his success is the result of “being in the right place at the right time. … All of those years (Principal) did very well. It was just the kind of setting you wanted to be in.” He adds many people helped him along the way, providing suggestions or criticism when needed. “They gave me a freshness of thinking,” he says.

Untapped advice

Hurd encourages those hoping to progress to the next step in life to “work very hard. … If you take a room full of people, and half work hard while half just get by, and 30 years go by, well, it’s self-evident which half will be more successful when you examine those two groups,” he says.

The city’s greatest accomplishment

“The engagement of the business community and their efforts to make it a better place to live,” he says, adding his view was shaped by former Principal Chairman Robert Houser, who believed that a strong community will benefit the companies in it.

Making progress

Like others, Hurd is eager for the completion of the $70 million Principal Riverwalk, which has taken more time than initially planned to reach its final phases. But he believes the wait is worth it. Hurd calls the set of sculptures by Japan native Jun Kaneko “a terrific addition” to the city (as of press time, the sculptures were scheduled to be installed this fall along the Riverwalk). He would also like to see the city offer more public transportation options through a bike-sharing program and by improving the D-line Downtown Shuttle. “I’d like there to be more opportunities for people to move about the city,” he says. Hurd also believes that downtown beautification efforts, such as planting flowers along roadways to create streetscapes, add a strong sense of place. He cautions city leaders not to be shortsighted and eliminate such plantings in times of tight budgets. “I don’t want them to let that slip away,” he says.

Giving back

Hurd, who has served as chair of The Nature Conservancy in Iowa, a board member for the Des Moines Arts Festival and board chairman of the Community Foundation of Greater Des Moines, says his passion for giving back to the community increased over time. “You want to give back as much as you can, because where you are today comes from the help of others,” he says. “And now it’s your turn.”

Mary Kramer

Mary Kramer

Written by Chelsea Keenan

Mary Kramer, 77, has spent a lifetime forging a path in a male-dominated world. Early in her career, she was one of the few female school administrators in the state. After then working at Younkers Inc. as corporate personnel director for six years, she joined Wellmark Blue Cross and Blue Shield in 1981, where, as vice president of community relations, she was the first female director. Kramer, a Republican, was elected to the Iowa Senate in 1990 and in 1997 was the first woman to be elected as Senate president. She also served as U.S. ambassador to Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean from 2004 to 2006.

Throughout her career, Kramer, who succeeded in predominantly male professions while raising two children with her husband, Kay Kramer, was an advocate for women in the workplace. A mentor to and cheerleader for young girls and older women alike, Kramer says that she has always fought for women to have the freedom to make their own choices. “I don’t ever want there to be judgment as to what those choices are,” she says.

Colleagues praise Kramer’s integrity, ability to find solutions and active leadership style. “Mary is brave,” Kaye Lozier, director of donor relations at the Community Foundation of Greater Des Moines, said in nominating Kramer. “Her strong core values serve her well in leading others through difficult situations (and) at times taking an unpopular stand and being the only woman at the table.”

“Recently, a young woman remarked to me, ‘I want to be just like Mary Kramer when I grow up,’ ” Mary Stier, founder and CEO of Brilliance Group LLC, said in nominating Kramer. “To which I replied, ‘We all do.’ ”

Keys to success

During her 12 years in the Iowa Senate, “I tried not to get outraged more than once a week,” Kramer says. Another important lesson she says she learned over the years is one many politicians today seemingly have forgotten: compromise. “You can’t always get everything you want in a bill,” she says. “Sometimes you have to give things up; people have lost that.”

Kramer says a sense of humor also helped her along the way, in both politics and business. “When I first started at Younkers, I walked into this very elegant room, with very elegant tablecloths and looked around at all the men in their very elegant dark suits—meanwhile I’m in a red blazer—and I said, ‘Who died?’ ” she recalls. “But I knew those who were amused would work with me.”

Giving back

“To whom much is given, much is expected,” Kramer says of her philanthropic philosophy. She’s been involved with, among other organizations, the Iowa Chronic Care Consortium, Girls Scouts of Central Iowa, the Civic Center of Greater Des Moines and Iowa Public Television. “I was either blessed or cursed with very high energy, and as my husband says, it’s better for everyone if I’m highly engaged,” she says.

Untapped advice

“You can choose your own happiness,” she says. “Bloom wherever you’re planted.” Using an example from early in her career, Kramer left Iowa City and her job in education after her husband was transferred to Des Moines. “We went even though I didn’t know what we’d find in Des Moines,” she says. She couldn’t find a job in education, which led her to seek opportunities in business, where she soon landed a job at Younkers. She never looked back. “You just have to be willing to take the risk,” she says.

Best thing to happen to Des Moines

The metro area “has become attractive to young people,” she says, the result of strategic choices made by area leaders.

Hobbies

Kramer, who received a bachelor’s degree in piano performance from the University of Iowa, still loves to play. But what she appreciates the most in her retirement is spending time however she pleases, she says, whether attending her granddaughter’s volleyball game, cooking, traveling with her husband or playing golf.

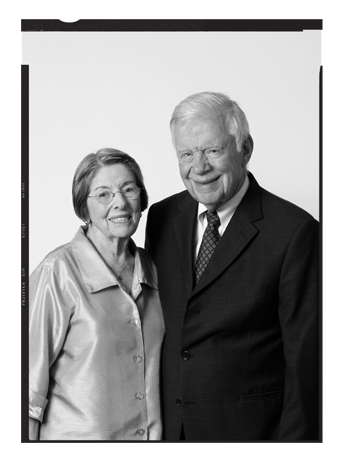

R.W. and Mary Nelson

R.W. and Mary Nelson

Written by Jane Schorer Meisner

There was a time when R.W. “Bud” Nelson dreamed of helping others by becoming a doctor, and Mary Nelson hoped to help young people by teaching home economics. But after earning biology and chemistry degrees from Drake University, R.W. had no money for medical school. And Mary, an Iowa State University graduate, left teaching to become a welfare caseworker for Polk County.

Half a century later, the couple’s company, Kemin Industries Inc., affects the lives of more than 1.4 billion people worldwide every day, not only through the products it manufactures, but also through the Nelsons’ donations of time and service, from Des Moines to far-flung corners of the world.

R.W. quit a job with a chemical company to found Kemin in his home in 1961. Mary managed the business end from their family room. Today, the Des Moines-based company manufactures more than 500 ingredients used by the feed and food industries, operates in 90 countries and employs more than 1,400 people in a workplace culture that encourages employees to become visionary and philanthropic leaders.

Despite their success, the Nelsons, both 85, remain humble, says Bill Lillis, an attorney with Lillis O’Malley law firm. “With the wealth that they’ve accumulated, their humility has always impressed me,” he says, adding the Nelsons are “an example to all of us. Their giving is very methodical and well thought out. It’s as a team, and what a team they’ve been. They’re just rock solid.”

Giving back

R.W. recalls that his Catholic parents always tithed, even through rough years in the 1930s. So when they first married, R.W. and Mary began systematically donating 10 percent of their income. Today, they say they donate 25 percent of their personal income to charity.

They also give their time. Mary has served on numerous local boards, including Anawim Housing, Holy Family School, Dowling Catholic High School, Living History Farms and the Catholic Diocese of Des Moines. R.W. served on finance committees at Dowling and Sacred Heart School, and on the first diocesan school board.

Corporate giving

The Nelsons’ personal philanthropic philosophy extends to their company. Because Kemin has locations around the world, its charitable causes are widespread. The Nelsons encourage employees to donate to disaster relief efforts by offering to match the amount they raise. In Des Moines, the Nelsons and Kemin employees have helped underprivileged children and low-income families through agencies such as Youth Emergency Services & Shelter and Greater Des Moines Habitat for Humanity.

Education is key

“Today, on the floor in manufacturing, (workers) need a lot more skills than someone who dropped out of high school,” Mary says. “And it’s the technical type of manufacturing you want in the corridor from Des Moines to Ames.” R.W. agrees. “If you want high-paying jobs, you have to have the skills to fulfill the work,” he says.

Getting personal

R.W.’s given name is Rolland Wade Nelson. He moved with his parents to Des Moines from Kansas City, Kan., in the 1930s. When he first met Mary on a blind date, he was more interested in her roommate. But he soon came to his senses, and the West Des Moines couple now has been married almost 60 years. They have five children and 14 grandchildren.

Untapped advice

Save money. When the Nelsons were first married, R.W.’s employer was unpredictable. “They fired him once on Saturday and hired him back Sunday,” Mary says. “Because we were always concerned, we saved money. So when we started our business, we had $10,000. That was quite a bit of money in 1961.”

Serve your community. “You’re part of the community,” Mary says. “It’s your home, and you want to make it a good place to live and work in.”

Divide your time. The Nelsons believe that work, family and community are all important. “Balance your life,” R.W. says.

Tom Urban

Tom Urban

Written by Kyle Oppenhuizen

For Tom Urban, “retirement” doesn’t mean long days on the golf course or at the country club. Instead, the energetic 78-year-old is actively leading major community projects. “The problem with growing older is you gain a lot of experience and then you die,” Urban says. “So what was the purpose of gaining all that experience? I suppose it’s self-serving in the sense that whatever talents I have, I ought to continue to exercise (them) in the community.”

Currently, he’s putting those talents to work as co-chair on the Capital Crossroads Urban Core initiative. He’s also part of the core team, along with J.C. “Buz” Brenton, Janis Ruan and Fred Wetiz, that’s leading the efforts to raise $11.6 million to revitalize and expand the Des Moines Botanical & Environmental Center into the new Greater Des Moines Botanical Garden. Such leadership is nothing new for Urban. In 1968, when he was just 33, he was elected mayor of Des Moines. He then joined Pioneer Hi-Bred International Inc., where he eventually served as chairman, president and CEO until retiring in 1996.

Urban spent a few years teaching at Harvard University and some time in Florida before moving back to Des Moines full time three years ago. Weitz, who ran The Weitz Co. until 1995, says that it’s no surprise that when Urban returned to Des Moines, “he just dived right in. He was mayor early on, and (through) that experience (he) got interested in the welfare of folks who weren’t so well off, and he’s always, ever since then, been interested in that part of the community. When he decided that he wanted to, in a sense, re-enter the activities of the community, that’s where he has been most effective, most interested, most involved.”

Mayor

As mayor, Urban says he learned “the importance of leadership, the importance of being able to clearly articulate outcomes that you think others ought to embrace. The ability to sell ideas. The willingness to understand the details and elements of the decision you are going to make.”

Being a mentor

Urban says mentoring others is highly rewarding, especially in the corporate world. At Harvard, he says he found the semesters to be too short a time period to mentor students. But at Pioneer, he was able to work closely with younger people over a longer period of time.

Dealing with challenges

Urban has what he calls a “train theory.” He doesn’t know what is going to happen day to day or month to month, but he continually tries to prepare himself intellectually and morally to meet new challenges. When the train comes by, “I could either decide to get on or get off,” he says. “And if I get on, then immediately I’m challenged because I’m doing something that I’m not used to doing. And I find that exciting.”

Regret

Urban wishes he would’ve spent more time with his wife, Mary. He sees their four children take a different approach to married life, he says. “I probably didn’t involve her as much as I see my children involving their spouses,” Urban says. He uses that lesson when he mentors others. “To really understand someone else, it takes a lot of work,” he says.

Untapped advice

“Take time to be involved in your community, whether it’s your church or a particular organization,” Urban says. “We just need all the citizen involvement we can get.”

Most significant memory

As an undergraduate student at Harvard University, Urban was challenged to think differently about the world than he had up to that point, he says. “You were exposed to extraordinary minds,” he says. When he was 21, Urban spent time with the American Friends Service Committee working with indigenous people in El Salvador, who were thought of as “animals” by that country’s leadership. “It was a whole different vision of how some humans view others,” Urban says. “To see that in action really gave me a deeper social consciousness than I think I might have otherwise had.”