Writer: Tim Paluch

Photographer: Duane Tinkey

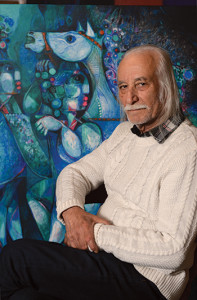

A man at rest but not yet at peace, Amer al-Obaidi pauses only briefly from his life of painting, cooking and communicating online with family and friends flung across continents by the devastation of their homeland.

Amer al-Obaidi drove his family to a busy Baghdad shopping district to buy clothes for his daughter’s upcoming birthday.

It was January 2006, and sectarian violence and terror attacks had escalated throughout his home country of Iraq. Businesses closed. Friends, neighbors and colleagues were kidnapped or killed as extremists began to target members of Iraq’s cultural and intellectual elite—men like al-Obaidi, a prominent artist whose paintings sold for tens of thousands of dollars and were exhibited throughout the Middle East.

Al-Obaidi’s son, Bader, a 29-year-old with Down syndrome, preferred to wait in the car on those shopping trips. Bedor, his teenage daughter, often stayed with her

brother, who would run his fingers through her long dark hair in the back seat. But that day, she joined her parents to shop.

The first of two bombs went off soon after al-Obaidi, his wife, Sawsan, and Bedor walked into a store. Bader was killed. Shrapnel pierced Sawsan’s foot. Doctors later amputated her right leg below the knee.

A letter arrived a month later. Inside were a threat and a bullet. The artist, still grieving the loss of his son and helping his wife recover from her painful injuries, packed his family and what he could fit into a car and made a harrowing drive out of Iraq in the dark of night toward Damascus, Syria, leaving behind a lifetime of accomplishments, memories and his beloved artwork.

This is home now: a plain brown brick ranch house on a long, hilly Windsor Heights street, with space outside to plant vegetables and space inside to paint—al-Obaidi’s true passion, a piece of himself the chaos that drove him from his native country could never steal.

The home holds al-Obaidi’s private art collection of his own work, all but a handful of pieces painted in Iowa since his family landed here in the summer of 2008 as refugees. In America, he has thus far been unable to replicate his past success, and his paintings sell far less frequently and for far less money, but still he is prolific. He paints every day on canvases bought from craft stores or thick pieces of brown paper used between stacks of wood pallets from Sam’s Club. Employees there save the paper to give to him for free.

The entryway is narrowed by large canvases and framed prints leaning against a wall. Paintings fill nearly every corner of wall space in the hallways and bedrooms and sitting areas, and dozens more are stacked in the dark basement and the small spare bedroom he uses as painting studios. His work is abstract: bold with color and life, but also teeming with a sense of frustration, anguish and disillusionment about war and its effects on humanity.

Above: Four small paintings of doves are the only artwork that accompanied al-Obaidi on his journey to the United States. They represent members of his family.

The 72-year-old al-Obaidi, with long white hair and a mustache to match, sits on a couch beneath a large canvas of vivid hues depicting an entangled mass of horses and men. His English is better than he realizes, but he speaks about his past through his daughter, Bedor, now 25, between sips of strong, dark Turkish coffee, occasionally chiming in with his broken English.

He was born the fourth of six children in a wealthy Baghdad family. As a boy of 10 or 11, he found himself mesmerized by patterns in the dry dirt created when it cracked under the hot Iraqi sun. So he cut out a block of earth, let it harden in the sun for two days, and used a knife to create his first sculpture.

He showed it to his father, who recognized his talent. “When my father saw this, he go to the market and he bring me papers and colors and clays and he said, ‘Take this and go paint,’ ” al-Obaidi says.

His early paintings focused more on traditional images of Iraq, but after the first Gulf War of 1990-91, when bombs destroyed homes and buildings in his neighborhood, al-Obaidi’s work became more political. He began painting broken chairs, with wounded or dead men slumped over them.

“War will kill everyone, on all sides,” he says. “Everyone is a victim of war.”

His reputation grew. In 1995 he quit his administrative job to become a full-time artist. Life for his family was simple, comfortable.

Then war and violence returned.

Al-Obaidi’s demeanor changes, and he grows quiet, when the conversation turns to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, led by the United States, and the prolonged Iraq War that followed. “Do you really want to talk about this?” he says.

“What can I tell you about the days, or the bombs, or the Iraqi army or the American army?” He lets out a deep sigh and wipes his hand over his eyes and brow. “It’s very terrible to remember that time. A lot of people died, a lot of people were put into the prisons, a lot of people died in the streets.”

American troops walked the neighborhood and searched homes for weapons. When they learned who al-Obaidi was, some took photos with him. But soon the area, like the rest of Baghdad, became more dangerous and more violent. Neighbors, including a scientist and a well-known heart surgeon, were murdered. One of Bedor’s friends watched masked men execute her father, a member of the Iraqi military.

After the bombing that killed his son and disabled his wife, al-Obaidi feared for his life. Religious extremists and terrorists—“professional criminals,” he calls them now—targeted men of influence, people of all faiths.

Then the letter arrived, with a bullet inside, giving his family three days to leave the country. They waited until nightfall, told no one, and drove west out of Iraq, on a road once used by the American military but now monitored by al-Qaeda and other fighters.

The family arrived in Damascus the following day. This was Syria before the civil war that decimated the country and led to the great refugee crisis. They lived in a villa outside the city in an area that was calm, welcoming and beautiful. Al-Obaidi painted constantly. But Sawsan’s condition worsened—she was also losing her sight—and friends

persuaded them to leave for a new life in Europe or America.

They applied for refugee status from the United Nations and were assigned to the United States. In August 2008, after rounds of security and background checks, al-Obaidi, his wife and their daughter boarded an airplane with two suitcases and a few pieces of his art rolled up in a canvas for a place they had never heard of and knew nothing about: Iowa.

Many of them were Iraqi business owners and middle- and upper-class intellectuals. Some had worked as interpreters for the American military or contractors. All were targets of the rising violence and could not return home.

Wuertz recalls al-Obaidi coming to the LSI offices during a staff meeting on Sept. 11, 2008. He had sketched some beautiful drawings of doves, symbols of peace, and presented them to the employees there.

“It was sort of his way of sharing in the grief of what had happened on Sept. 11, sharing his sadness and condolences,” Wuertz says. “It’s something that I will always remember—a telling and powerful statement of who these refugees are.”

Funding was sparse, so refugees ended up in shoddy homes. Bedor and her father chuckle now when they talk about their first Iowa apartment: a small, dirty unit off Hickman Road that had cockroaches and little room for him to paint. Bedor compared it to living in a refugee camp.

Jane Scanlon, then a volunteer with LSI, became close friends with the family and eventually helped them find their Windsor Heights rental home.

“I felt this bond with them because of the tremendous contrast of the life they came from and the life they are in,” she said by phone from her home in the mountains of Colorado, where she moved in 2013.

Sawsan, confined to a wheelchair, is blind in one eye and losing what remains of her vision in the other. She can no longer watch her husband paint.

Bedor danced ballet in Iraq and enjoys writing and studying art. She has taken some college courses but still struggles to find her place in her new home. “I’ve been lost,” she says. “I was born in a war, I grew up in a war, and I left my country in a different war.”

Through all the struggle, somehow, al-Obaidi and his family have kept a remarkably positive attitude, Scanlon says.

One of the first paintings al-Obaidi created in Iowa—an expressionist piece of bright colors and geometric shapes enveloping seated human figures—now hangs in her living room. She designed her new home around it.

In recent months, Middle Eastern newscasts have been the soundtrack to life in the al-Obaidi home, providing constant updates on the violence in the family’s former homes of Iraq and Syria, and the epic refugee crisis created in its wake.

The family watched with concern as American political campaign rhetoric swirled about Middle Eastern refugees who, like them, are trying to escape their homes to survive the violence. Al-Obaidi wants the United States to get more serious about fighting terror: less bluster and talk, more military action. But he also wishes America would be more accepting of refugees.

“All this hate,” he says. “No one shares the true story of the refugees.

“It’s way more difficult than what I’ve gone through. I feel their fears. I feel their pain. I feel their sorrows for sure.”

When his wife or daughter forces him to change the channel, he often retires to another room with the family’s iPad, covered in a pink shell, and squints to watch videos and read Facebook updates from friends and family. His three surviving siblings settled in Canada and Europe, and past colleagues and friends live around the world, though few are in the United States.

The artist doesn’t sleep much—a few hours each morning and an afternoon nap. The fame and cosmopolitan lifestyle of his past are gone. The disarray in the Middle East has dried up the art market in which he once prospered, and breaking into the U.S. art scene has proved elusive, largely due to the language barrier and the challenges of starting over and getting his name out at this stage in his life. Now, he takes care of his wife and the house, he cooks, and he sketches and paints. Always sketching and painting, often through the night when inspiration calls.

When he first arrived in Iowa, he showed some of his work at a few local churches, but the Des Moines Social Club hosted his first professional American exhibit, “Lost in the Maze of Immigration,” last fall.

“There was so much talent here that was not yet exposed in our community,” says Cyndi Peterson, the Social Club’s chief operating officer, who invited al-Obaidi to showcase his art there.

Andrew Graap attended the exhibit opening and was blown away as he walked past each of the 17 al-Obaidi paintings on display. He returned the next day and purchased three pieces for $6,000, about a tenth of what they might have sold for a decade ago.

“People have looked at them and said they seemed scary and fearful,” Graap says. “I look at them and see mostly confusion, a representation of the journey he has unfortunately had to experience over the last few years.”

Al-Obaidi says he feels deep sadness every time he sells a painting. Each work of art is so personal to him, so much a part of his being. Sometimes he will try to re-create paintings from his past, but the result is never quite the same.

This is a man who has lost so much—his career and fame, his home, his only son, his sense of comfort and place in the world—and he vows to never stop painting, to never lose this part of himself.

“This is my world,” al-Obaidi says. He gently thumps his chest. “It is connected to my heart and to my soul. It is speaking from my spirit.”

Tim Paluch is a freelance writer based in Des Moines. After more than a decade as a reporter and editor in the newspaper business, he left in 2013 to become a stay-at-home father to triplet girls. When his 2-year-old daughters allow it, he sometimes still writes things.