Writer: Michael Morain

If Louise Noun were still around these days for the Time’s Up movement, she’d probably say it’s about time.

After all, she was a stalwart feminist, a hard-charging social activist, and an art aficionado who started collecting artwork by women more than 40 years before Hollywood rallied behind movies by female directors and producers. Paintings by Frida Kahlo and Agnes Martin hung on the walls of Noun’s seventh-story apartment at the Park Fleur long before the rest of the world had even heard their names.

Noun “wasn’t interested in feminist art, necessarily. She was interested in strong work by artists who were female,” says Amy Worthen, curator emerita of the Des Moines Art Center’s print collection who was Noun’s longtime friend.

By the time Noun ended her life at age 94, in 2002, she had given the Art Center more than 200 artworks by some of the most talented—and most overlooked—female artists of the 20th century, from the surrealist painter Hannah Hoch to the multidisciplinary star Kiki Smith. The museum will display many of these works in a show called “In the Spirit of Louise Noun,” which opens June 9.

“Louise Noun’s influence is still very much alive,” Art Center curator Alison Ferris says. “The artwork she brought to the Des Moines Art Center has shaped how we collect art and how we even think about art.”

Noun was an active member of the museum’s board of directors and acquisitions committee, and she championed early 20th-century artists, like Hoch, who were relatively unknown during their lifetimes but were later recognized among the greats. She also made a case for contemporary artists, like Smith, who charged headfirst into social justice, sexual politics and other controversial territory.

For the new show, Ferris highlights Noun’s enduring influence by choosing a dozen works from her collection and matching them with 20-some other pieces from the museum vault. Most are paintings and prints, but a few sculptures are in the mix, too, and they’re all the work of women.

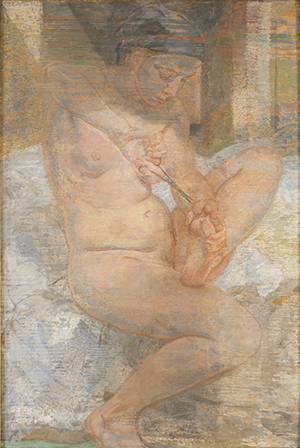

Noun’s portrait of a nude by Isabel Bishop, for example, will hang among several other nudes, including Wangechi Mutu’s slinky cast-bronze mermaid, called “Water Woman,” and Cecily Brown’s painting “Half-Bind,” in which a female figure emerges from a jungle of abstract brushstrokes.

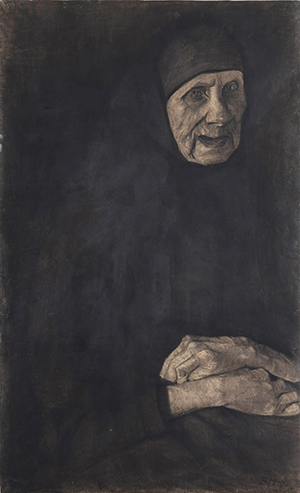

On another wall, Noun’s 1899 drawing of an “Old Peasant Woman” by Paula Modersohn-Becker will hang near one of the Art Center’s latest acquisitions, a Depression-era photo called “White Angel Breadline” by Dorothea Lange. Both works present their subjects with “dignity despite their poverty and plight,” Ferris says.

Noun would be just as interested in contemporary art as in her own collection, Ferris says, so the curator gave herself some leeway—hence the “In the Spirit of” title.

That same spirit would be interested in the show’s timing, too, on the 40th anniversary of the Young Women’s Resource Center, which Noun helped establish for teen moms, sexual-abuse victims and others who could use some extra support. When the nonprofit’s leaders asked if the Art Center would help celebrate the anniversary by hanging up a few of Noun’s pieces, Ferris offered something better: She promised a whole show instead, and has invited the nonprofit’s young women to see the show for themselves and learn from its lessons about body image, self-esteem and resilience.

“I hope [Noun] would appreciate it if she were here today,” Ferris says. “Her perspective, her politics—we want to keep her memory alive as a progressive role model for this community, especially in the times we’re living in right now.”

Exhibit Details and Related Events

“In the Spirit of Louise Noun” will be on display June 9-Sept. 2 at the Des Moines Art Center. Related events include a panel discussion called “Celebrating Louise Rosenfield Noun in Five Stories” on June 10, from 1:30 to 3:30 p.m., in Levitt Auditorium. Moderated by Amy Worthen, the panel will include Rekha Basu, Karen Mason, James Demetrion, Terry Hernandez and John Tinker. Admission to the discussion is free but reservations are required. On June 28 at 6:30 p.m., senior curator Alison Ferris will lead a gallery talk. For more information on these events, visit desmoinesartcenter.org.

Isabel Bishop (American, 1902-1988), “Nude, no. 2” (1958); mixed media on Masonite, 31 3/4 x 21 1/2 inches. Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections.

Isabel Bishop (American, 1902-1988), “Nude, no. 2” (1958); mixed media on Masonite, 31 3/4 x 21 1/2 inches. Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections.

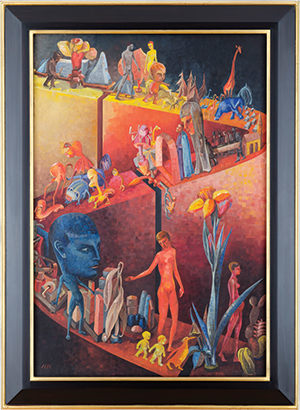

Cecily Brown (English, born 1969), “Half-Bind” (2005); oil on linen, 103 × 83 × 1 1/2 inches.

Nathan Emory Coffin Collection of the Des Moines Art Center.

Kiki Smith (American, born 1954), “Bandage Girl” (2002); bronze with silver nitrate patina, 28 x 14 x 18 inches. Nathan Emory Coffin Collection of the Des Moines Art Center.

Paula Modersohn-Becker (German, 1876-1907), “Old Peasant Woman” (1899); charcoal drawing on paper, 31 7/16 × 19 1/4 inches. Des Moines Art Center’s Louise Noun Collection of Art by Women.

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965), “White Angel Breadline” (1933); gelatin silver print, 13 1/2 × 10 1/2 inches.

Activism Through Art

Louise Noun was born in 1908, the third of Meyer and Rose Rosenfield’s three children, and grew up in a comfortable South of Grand house on 37th Street. Her father and his wife’s brothers co-owned a department store called Harris Emery Co., which merged with Younkers in the 1920s. Her mother was a socialite and expected her daughter to follow suit.

As a girl, Noun often felt her parents favored her brothers, but they sent her off to good schools. She earned a bachelor’s degree from Grinnell College and a master’s degree in art history and museum management from Radcliffe/Harvard in 1933.

When she asked one of her professors about which jobs she should pursue in New York, he suggested she should return home to Iowa and get married.

“I’m surprised she didn’t haul off and slug him,” former Art Center director James Demetrion said over the phone from his home in Arlington, Virginia. He led the Art Center from 1969 to 1984 before heading off to direct the Hirshhorn Museum until his retirement in 2001.

But Noun wasn’t always so self-assured. She was shy as a child and often unhappy in her role as a doctor’s wife. She had married Maurice Noun, a Des Moines dermatologist, and they built a house on St. John’s Road, right behind her parents’ place.

“She had this constant feeling of personal inadequacy,” says Amy Worthen, curator emerita of the Art Center’s print collection who was Noun’s friend. “But then she realized it was because she was being kept down. And eventually she turned that depression into anger and activism.”

Noun had always participated in civic groups around town. In 1948, she became president of the local chapter of the League of Women Voters. In the 1950s, she served on the Des Moines Plan and Zoning Commission, and in 1964, she became president of the Iowa Civil Liberties Union. But after her divorce, when she was 61, she kicked it up a notch.

She co-founded the Des Moines chapter of the National Organization of Women in 1971, the Young Women’s Resource Center in 1978, and the Chrysalis Foundation in 1989. Three years later she sold her Frida Kahlo painting for $1.65 million to create and endow the women’s archives at the University of Iowa, with help from her friend Mary Louise Smith.

When Noun discovered that her brother Joe Rosenfield’s name – but not her own – had landed on a list of President Richard Nixon’s enemies, “she was just furious,” Demetrion said. “She thought it was prejudice against women.”

Noun collected art along the way, but it wasn’t until the mid-70s that she combined that passion with her politics. At Demetrion’s suggestion, she bought a 1909 painting by the Russian artist Natalia Gontcharova, whose work had been virtually hidden behind the Iron Curtain. And from then on, Noun shifted her attention to artwork by women. She sold a smallish bronze by Henry Moore to free up funds to buy even more.

“With her art-history background, she began to realize that it was time to sell off all the work by male artists and start buying work by women,” Worthen says.

And she just kept at it. As Noun’s collection grew, so did its reputation. Gallery owners and artists started making her offers because they wanted their work to be included and the prestige that inclusion conferred.

The University of Iowa Museum of Art mounted an exhibition of Noun’s collection in 1990 that revealed just how far she had pushed ahead of the curve.

“The works Ms. Noun has chosen to collect are by artists about whom we know little and whose genius is just beginning to be recognized,” the late Mary Kujawski, who directed the university museum, wrote in the show’s catalog.

But as much as Noun loved art, she was always more interested in the artists themselves.

“With the diligence so characteristic of her,” Kujawski wrote, “she began to learn about the remarkable women who had produced the paintings she collected, and, more important, she began to learn from their lives.”

She’s still teaching, too. The lessons of Noun’s own life continue.

Sterling Ceramics

In grade school, most kids get a chance to make some clay pots. They’re usually a little lumpy or crooked and aren’t much good for holding water.

The artist Sterling Ruby makes pots like that, too, but on a bigger scale. Some are as big as bathtubs, covered with chunky globs and garish glazes.

When Des Moines Art Center Director Jeff Fleming spotted three of Ruby’s basins at a 2014 show in New York, he was “immediately mesmerized,” he says. “You know how things sort of stick in your head and you keep thinking about them? I wanted to know more.”

So after a trip to Ruby’s studio in Los Angeles and careful planning—it’s not easy to ship ceramics across the country—the Art Center will present the first museum show devoted to Ruby’s ceramics. About 30 of his pieces, big and small, will open June 9 (the same day as “In the Spirit of Louise Noun”) in the museum’s I.M. Pei wing. The exhibit runs through Sept. 9.

Throughout history, people have shaped clay into everyday objects and fine art, making everything from a plain old bowl to a porcelain vase.

In some cultures, such as Japan’s kintsukuroi tradition, repaired pottery is considered more beautiful than if it were brand new. When pieces break in Ruby’s kiln, he adds the remnants to his next project to capture the history

of his process.

“That diverse history fascinates me,” Fleming says, “and it fascinates him, too.”

Des Moines Art Center

Sterling Ruby: Ceramics

June 8 – Sept. 9, 2018