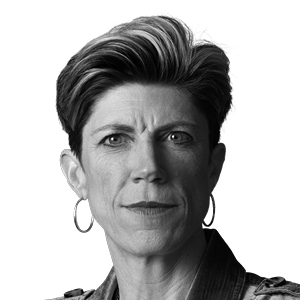

Above (from left to right): Eileen Gebbie, Alexandra Gray, John Harper, Jan Jensen, Tracy Lewis, John Forsyth.

Writer: Luke Manderfeld

Photographer: Duane Tinkey

We at dsm magazine are proud to stand with our diverse neighbors and present the second annual LGBTQ Legacy Leader Awards. Once again, we have partnered with the advocacy group One Iowa to honor the civic contributions and achievements of Iowans who have persevered despite prejudice to make our state a better place for all. We also have selected one individual from outside the LGBTQ community to honor as an Ally, someone who has embraced and promoted LGBTQ Iowans as friends and colleagues.

Learn about the honorees below, and join us in honoring them at a virtual reception at 3 p.m. June 18. Also at the event, the newly announced One Iowa Leadership Institute class will be presented.

Eileen Gebbie

Fighting Fear

Christmas Eve is typically a day of happiness. For Eileen Gebbie, the 2019 celebration began with disappointment.

It was an unseasonably warm morning in Ames, where Gebbie is the pastor at the United Church of Christ. Already she was dreading what faced her: Just a few days before, the man who had set the church’s rainbow-colored LGBTQ flag on fire early that year had been sentenced to 16 years in prison. The blowback was swift and severe. The punishment was too harsh, dissenters said, despite the fact it was a hate crime and the man was a repeat offender.

They directed their anger at the church, which is inclusive to people regardless of sexuality. Hate messages flooded in, and many of them carried anti-LGBTQ sentiments.

“The backlash was substantial and unrelenting. It was eye-opening,” Gebbie says. “I don’t believe there’s a world in which God condemns anyone to death or suffering. Being gay is a biological reality, and this made me dig in even more.”

Gebbie has long been a proponent of inclusivity and acceptance. She was born in St. Louis but spent her formative years in Portland, Oregon. In high school, Gebbie lived with her openly gay aunt and partner for a year. Her experiences made it easier for Gebbie to come out as a gay woman when she was 23.

Gebbie, now 46, was raised in a religious household, but left the church in her early 20s because of the vitriol some Christians expressed toward the LGBTQ community. By her late 20s, however, she felt a pull back to the church. It took her 10 years to finish seminary while working in the nonprofit field, but by 2012, she found a role as a church minister in California. In 2015, she and her wife, Carla Barnwell, moved back to the Midwest to serve the church in Ames.

From the outset, Gebbie emphasized acceptance of all and became a mentor to many, both within and outside the LGBTQ community. In addition, she serves as the founding board member of the Story County Housing Trust Fund and has frequently written guest editorials for the Ames Tribune on social justice issues. She also has worked with the Ames Public Library to expand programming for LGBTQ youths.

“Eileen consistently uses her voice, her platforms, her institution and her leadership to practice inclusivity,” says Ben Schrag, a member of the congregation. “She creates places of safety and gives relief to those who struggle with the challenge and pain of being [an outcast].”

Alexandra Gray

Searching for the Stage

Alexandra Gray grew up on the southwest side of Chicago in a family of accomplished singers in the local African American music scene. As a youth, Gray sang, danced and was enthralled with musicals. She started to take the stage more seriously in her teenage years, first performing professionally in the Houston Grand Opera version of “Porgy and Bess” in the mid-1980s.

At the same time, Gray was finding herself. Living as a man, Gray knew from an early age she was gay, but by her early 20s, she started to understand herself as a transgender woman.

“You get up every day, and someone says that you’re supposed to be this one day, and you know in your heart of hearts that you’re not,” Gray says. “For me, being creative was my outlet. I had a lot of people who called me [names] and bullied me in school. But they couldn’t take away that I was a damn good singer.”

Gray came out in 1997, but her performing career took a hit. At the time, transgender people of color couldn’t find work in the theater industry, Gray says. By her mid-20s, she started working in gay bars to make ends meet. She wouldn’t return to the stage for two decades.

Five years ago, Gray moved to Des Moines after struggling to find housing and employment in Chicago. Iowa was familiar to her as she had friends in the area and had attended Luther College in Decorah. She immediately became involved with the local LGBTQ community and also serves on Primary Health Care’s prevention advisory council.

Mentorship has long been a passion for Gray. About 25 years ago, she lost her two grandmothers and several other family members in the span of about a year. That sparked her desire to connect and help others, particularly drag performers, transgender individuals and LGBTQ people of color.

Gray is acutely aware of the threats that face transgender women of color and is an outspoken advocate for LGBTQ rights. According to the Human Rights Campaign, 26 transgender or gender-nonconforming people were killed in 2019 in the United States, the majority of whom were black transgender women.

“Alexandra captures the attention of every person she ever interacts with,” says Daniel Hoffman-Zinnel, CEO of Proteus Inc. and former executive director of One Iowa. “Alexandra fights each day to stay alive and speaks at public events to put a face to transgender women of color.”

After 20 years, Gray, now 47, returned to the stage in 2016, playing the lead role in the Des Moines Community Playhouse’s “Sister Act.” Since then, she has dived back into the theater.

“This is what fuels my spirit, and so I’ve been pursuing the arts more,” Gray says. “I had to come to grips with who I was before I was able to pursue what I wanted to do and be genuine about it.”

John Harper

Changing the Narrative

John Harper has heard the heartbreaking stories, even if he hasn’t lived them himself. He spent several years on panels for the Governor’s Conference on LGBTQ Youth, listening as attendees poured their hearts out. Many had been kicked out of their homes. Others had been disowned by their families. Some were afraid to come out publicly.

It’s these stories that inspire Harper, 79, to be a steady force in the lives of young LGBTQ individuals. He’s owned that mindset since he was a young boy himself.

Harper grew up in Des Moines, where his parents routinely helped those less fortunate and impressed on him that with privilege comes a responsibility to give back. In the 1950s and early 1960s, being openly gay was almost an impossibility—it was criminalized in most states, and role models were not readily apparent.

By the time Harper acknowledged to himself that he was gay, in his mid-20s, he had already seen a number of his closeted gay friends marry women and have children.

Harper started working as an administrator with the University of Iowa in 1966, and he came out just a few years later. Unlike other gay individuals at the time, being open didn’t hinder Harper, who became a professor of English in 1976. He worked at a university that has long been inclusive to LGBTQ individuals, in a city that was progressive for the times. In addition, Harper was active in the local theater scene, a largely accepting community.

He remained relatively protected from discrimination until the early 1990s, when he returned to his religious roots.

As young as 9, Harper felt a calling to the church but turned away from religion after a bad experience during his college years at Stanford University. After turning 50, though, he wanted to make a change and in 1995 became the first openly gay cleric in the Episcopal Church of Iowa.

Religion is often a reason LGBTQ youths are afraid of coming out, fearing they’ll be alienated by their family and church, Harper says. He wants to change that narrative. For a number of years, Harper wore his clerical garb on National Coming Out Day, prepared to help anybody who needed it.

“I feel I’m in this privileged position, having faced almost no pushback or discrimination on this journey,” he says. “But at the same time, I listen to the stories of people around me and feel the price they’ve paid for trying to come out. For me, it’s an obligation.”

Harper retired in 2002 after 36 years with the University of Iowa. He’s still involved in the community, including with the ACLU of Iowa and Planned Parenthood, and has mentored hundreds of LGBTQ individuals.

“John is a generous and socially conscious booster of numerous causes,” says Ryan Crane, director of charitable giving for the Community Foundation of Greater Des Moines.

“He doesn’t just check the box—he lives it.”

Jan Jensen

Forging Ahead

Quitting seemed like the right choice—maybe the only choice. It was the late 1990s, and Jan Jensen was just understanding her sexuality as a gay woman. As the assistant head coach for the women’s basketball program at Drake University, Jensen worried that coming out would be a detriment to her team. At the time, there were few, if any, openly gay college coaches.

She walked into head coach Lisa Bluder’s office and offered to resign. Bluder didn’t accept.

“I didn’t want to let everybody down and hurt the program,” Jensen says. “Just like in every profession, there was homophobia. There were people using that as a reason to not send their daughters to play for your team. But thankfully, I had a great support group that helped me forge ahead.”

Jensen followed Bluder to the University of Iowa in 2000, where they turned the program into a perennial powerhouse. Jensen, associate head coach, became a highly regarded recruiter and coach, helping countless players improve their skills while serving as a mentor on and off the court.

Success is nothing new to Jensen. Growing up in the western Iowa town of Kimballton, Jensen averaged 66 points per game for her six-player high school basketball team. She became one of the most celebrated athletes in the area and played collegiately at Drake, eventually competing professionally overseas.

When Jensen returned to Iowa after her playing career ended, she had time to reflect. Away from the daily grind and dedication of an elite athlete, Jensen looked inward and realized she was gay. The first person she told was Julie Fitzpatrick, a former teammate at Drake, in 1997. They became lifelong partners and later married.

Coming out to her family and hometown was more difficult. Jensen was the homegrown star and revered in the area, and although her relationship with Fitzpatrick was accepted, it wasn’t openly discussed there. Then in 2007, Jensen and Fitzpatrick visited Kimballton with their newborn son, Jack (they also now have a daughter, Janie). In a crowded local dinner theater, a line formed to greet them and welcome the baby. It was one of the first times their relationship was embraced on such a deep level.

There were people of all ages, Jensen says. “I was in tears the whole night. I will never forget it. So much was said without saying anything at all.”

Over the years, Jensen, now 51, has worked with numerous charitable organizations, including the United Way of Johnson County, where she and Fitzpatrick co-chaired a record-setting campaign; and the Shelter House, which operates an emergency shelter and also permanent supportive housing units. She speaks throughout the state on leadership and team-building topics.

Jensen “has been a great mentor to the women on our team and the rest of the athletic department,” Bluder says. “She has been a sounding board and an ally to many of her peers and student athletes. Her leadership is unparalleled.”

Tracy Lewis

A Role Model for Many

In northwest Iowa’s Woodbury County, farm acres outnumber people. Row crops and gravel roads stretch to the horizon and beyond. This is where Tracy Lewis grew up in the 1960s and ’70s, the son of farmers and the youngest of three children.

He has fond memories of his childhood: Long days on the farm honed his work ethic and 4-H taught him invaluable skills. It was early in that upbringing that Lewis realized he was gay. But in his rural community, there were no LGBTQ role models. He remained closeted.

“It wasn’t a horrible existence, but I felt like there was no one like me,” he says.

Lewis attended Iowa State University, then began a human resources career at Principal Financial Group in 1984. On his first day, he met his life partner, Rick Gubbels. They kept the relationship a secret, but by 1989, Lewis thought the relationship would have to end if they couldn’t come out. The facade was too much to keep up.

“I was sick to my stomach, but one day I thought, ‘Why does it have to end?’ ” Lewis says. “I want it to go on forever.”

Lewis came out to his family members, who were accepting. Principal, long a proponent of inclusivity, accepted him as well. It was a weight lifted for Lewis, who could now live openly and honestly.

Today, Lewis is passionate about mentorship and community service. He and Gubbels have mentored dozens of LGBTQ individuals, serving as the role models Lewis never had. He also is a fixture among Central Iowa LGBTQ organizations and has served as a board member for the Des Moines Public Library Foundation, the Des Moines Arts Festival, the former StageWest Theatre Company, and the Iowa 4-H Foundation, reflecting his passions for the arts and for agriculture.

“Tracy has passion for many causes but more so for the LGBTQ community,” says Lynn Graves, a former co-worker and community volunteer. “Tracy never hesitates … to share his time, talent and treasure.”

Lewis, 59, is retired now after a successful career. He’s battling stage 4 prostate cancer and knows he has a fight ahead of him. As he crosses off bucket list items with Gubbels, Lewis wants his legacy to be about the lives he’s touched.

“You get very reflective when you’re told you have a certain amount of time left on this earth,” Lewis says. “I’m struggling in a lot of areas, but this honor shows me that maybe my life wasn’t for nothing.”

Ally Award

John Forsyth

Culture of Acceptance

Bragging isn’t John Forsyth’s strong suit. That became immediately evident in a recent interview in his window-clad corner office on the top floor of the downtown Wellmark Blue Cross and Blue Shield building.

A few Wellmark team members joined him for the interview. In telling his own story, he was quick to credit them at every turn, exhibiting the type of modesty that has made him an effective leader in moving Wellmark to the forefront of inclusivity in the workplace, including for LGBTQ individuals.

Forsyth, 72, has been the CEO of Wellmark Blue Cross and Blue Shield, the largest insurance provider serving Iowa and South Dakota, for 24 years. Throughout the past two decades, Forsyth’s vision has been to create an organization accepting to all.

In the late 1990s, Wellmark became one of the first organizations in Iowa to establish insurance benefits for same-sex couples. Forsyth oversaw the creation of the company’s Inclusion Council, which brings a wide range of voices to the decision-making table. Because of Forsyth, Wellmark supports only nonprofit organizations that agree to the company’s inclusion statement.

Forsyth was raised north of Detroit and studied engineering at the University of Michigan before transferring to Michigan State to finish his bachelor’s degree in economics—“I hated [engineering],” he says with a laugh. He worked with the University of Michigan in the 1970s and ’80s and joined Wellmark as CEO in 1996.

As a leader, Forsyth has embodied his parents’ teachings of acceptance. “It’s all about how you grow up, right?” he says. “I was raised that you should treat everybody how you want to be treated.”

He also realized how much sense inclusion makes from a business standpoint: “As a leader, if you want to get the maximum value, then you have a very diverse population that really should [foster] all kinds of different views and different ideas.”

Forsyth seeks to have open communication with his employees, which made an immediate impact on Tony Khuth, who lost a friend in the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting in Florida. Khuth, an employee and member of the LGBTQ community, reached out to Forsyth, who promptly announced Wellmark would donate $5,000 to the One Orlando fund and match employee contributions.

“That single act has forever shaped what being an ally means to me,” Khuth says.

Khuth’s story and others like it are one reason why Forsyth enjoys what he does. “It makes my day. I mean, that’s what it’s all about, right?” he says. “You want to have a great company, you have to have great employees. I just get excited each time I hear somebody that says, ‘This has made a difference in my life.’”