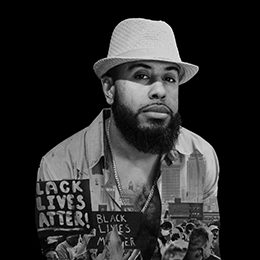

Photographer Janae Gray captured Billy Weathers as a musician, nonprofit leader, and civil rights activist. “I decided to interpret this visually by taking each image and creating a duotone exposure to give the portrait transparency—in retrospect, the same transparency Billy was sharing with me and others,” she says.

Writer: Kyle Munson

Photographer: Janae Gray

Billy Weathers grabbed the microphone, but this time he wasn’t onstage as a hip-hop artist, galvanizing 4,000 fans as the opening act for Lil Uzi Vert. He was on the streets as an activist, in front of the Des Moines Police Department, surrounded by a throng of protesters.

“I didn’t come here to explain white privilege,” he said. “I didn’t come here to explain the Black experience in America. And I certainly did not come here tonight to bring more hate into this world. I promise you that. I came here to motivate and share my opinions.”

That drew applause.

It was May 29, 2020. Weathers acknowledged the legitimacy of the crowd’s anger just several days after George Floyd, a Black man, was suffocated by Minneapolis police over an alleged counterfeit $20 bill.

“I come to you as a flawed man who’s trying to control what he can,” said Weathers, 29, framed by a beige fedora, bushy beard and torn blue jeans. He occasionally read from prepared remarks on his phone.

“We’re fighting a systemic racial injustice,” he said. “This goes a lot deeper than George Floyd or Breonna Taylor or Kalief Browder or Tamir Rice.”

The rally—hastily organized on Facebook by Weathers and his friends Michael Turner and Louis DeMarco without them realizing how quickly it would balloon—was one among countless such scenes in a historic year of civil rights protests worldwide. If the remedy to many of these stubborn social maladies were purely political, Weathers said, they would have been fixed long ago.

Data backs him up, including here in the capital city. The One Economy Report released in 2017 as a socioeconomic snapshot of Black Polk County detailed a vast wealth gap: The median income for Black households is $26,725, less than half the $59,844 median for all households.

Any serious hip-hop fan has heard the persistent thudding drumbeat of these problems for decades, verse after verse. Weathers began 2020 in his primary mode as a musician—his alter ego, rapper B.WELL. His 2018 album “The Hills” opens with the track “90’s Baby,” featuring news-anchor reports from the 1991 beating of Rodney King by the Los Angeles police—brutality filmed by a citizen long before livestreams from cellphones.

“Man, I can’t believe this shit is still happening,” Weathers says on the album, imagining himself as a young Black man in the early ’90s. “Hopefully catching it on camera will do something this time. I ain’t going to hold my breath, though.” (The officers’ eventual acquittal for the 1991 beating triggered the L.A. riots.)

That song slides into “Wake Up,” a “What’s Going On”- style warning to society about a “war on the poor” and “revolution on the way.”

Those sentiments on “The Hills” now sound eerily prescient considering in 2020 Weathers stepped forward to help his community navigate these very issues.

“I’ve grown as a human probably more this year than any year,” he says.

That rally was just the start. On June 2, Weathers helped lead some 800 protesters to the lawn of Terrace Hill, where they were met by dozens of Iowa state troopers. In coverage of the event, Weathers was shown locked arm-in-arm with an Iowa State Patrol commander as leaders on both sides tried to ease tensions.

That image caught the eye of Des Moines businessman Tony Rose. As was happening in homes everywhere, Floyd’s death and the resulting protests had sparked family conversations on race—in this case between Rose, 50, and his 25-year-old son. A scrappy entrepreneur, Rose grew up on the city’s east side among diverse neighborhoods and classrooms, embracing that diversity while also witnessing no shortage of blatant racism in daily life.

But now he was being challenged from within his own family to acknowledge a more 21st-century view of white privilege that recognized less obvious, more insidious, and more deeply enshrined inequities.

“It just struck a nerve when my son called me a racist,” Rose says. Then he saw Weathers wielding a bullhorn in images splashed across TV and social media.

“That’s when the light bulb went off,” Rose says.

Weathers’ Instagram feed (@b_well_) and overall social media game are strong. He strives to portray a photogenic and philosophical “fresh air of positivity” in a digital minefield that tends to vacillate between vapid and toxic.

Rose responded to Weathers’ nonviolent stance. The two didn’t know each other, but Rose got a phone number from Weathers’ ex-girlfriend—the most serious relationship of Weathers’ 20s that still evokes tears when he speaks of her.

Rose, whose Function House Hospitality Group helps stage large outdoor events, reached out and offered to literally amplify Weathers’ voice by lending him hundreds of thousands of dollars in PA gear and a cargo van.

He also figuratively amplified Weathers’ voice by arranging meetings with civic power brokers—politicians, attorneys and more, essentially tapping into the white privilege network at issue.

He encouraged Weathers to put an organizational framework to his community outreach and philanthropy that seemed to be growing more ambitious by the day.

Weathers and his team, Rose says, “aren’t coming with the fist, they’re coming with the voice and a message.”

Weathers performed at the “More Justice, More Peace” show last June, which featured local painters, poets and musicians. Show proceeds benefited his foundation, specifically the “Knowledge is Power” fund to help Des Moines Public Schools’ faculty, teachers, students and parents in need.

The puzzle pieces began falling into place for Weathers, in large part because he already had spent years—sometimes unwittingly, yet always with a genuine and methodical heart—building his support network, including among his own immediate family.

Weathers’ parents, Bobby and Jane, live in the East Village within eyeshot of many of the 2020 protests. They boomeranged back to Des Moines after Jane retired from the American Red Cross, wrapping a 35-year career that saw her evolve from the ground floor to divisional vice president.

“Billy probably gets his activism gene from me,” she says.

As a young white woman she took to the streets and marched against the Vietnam War in her hometown of Mason City. No social media: She and other activists mimeographed flyers at First Congregational Church to spread the word. Jane remembers her mother saying that one person can’t really make a difference. So the daughter dedicated her life and career to proving mom wrong.

“It may be a small dent, not a big dent,” Jane says of her abiding faith in activists’ collective and gradual influence. “But you can make a dent.”

She stood on the fringe of the crowd May 29 and watched her son launch the rally.

“I just cried,” she says. “It was really powerful.”

If Weathers inherited his activism gene from his mom, some of his Black father’s influence includes classic funk, soul and R&B records—the Gap Band, Cameo, Earth, Wind & Fire, etc. Bobby is the more reserved or even reclusive parent.

“I was social distancing when it wasn’t cool,” Bobby jokes. “I’ve always lived by that rule.”

Jane already had 5- and 7-year-old daughters when she and Bobby met in the ’80s. “I asked him to dance, and after that it’s history,” she says.

In a guest Instagram post last year for @blacklivesofdsm, Weathers talked about “always searching for my place”: “Growing up mixed you kind of have this identity crisis. Where you’re not really sure where to fit in. So I spent a lot of time in hip-hop music and basketball and football culture and rap and fashion and all of that.”

Another angle on Weathers’ perception of his duality is tattooed in cursive on his body as visible reminders: His right inner wrist reads “forgive.” His left, “undeniable.” Humility. Bravado. Sometimes in the same breath.

Last summer, Weathers led marches through the suburban streets near and around Valley High School.

Weathers grew up in Des Moines (living in Sherman Hill and Beaverdale) but at the start of eighth grade moved to Las Vegas with his family, following his mother’s career.

The diversity and dazzle of Sin City was a culture shock, but Weathers focused on football. One of his most triumphant moments is captured in a 2008 sports photo published in the Las Vegas Sun as the wide receiver holds a giant trophy overhead just after his team, the Wolves, had won the city championship.

Weathers then enrolled in Simpson College and returned to Iowa. He befriended Taylor Rogers—today his DJ and manager—as a fellow freshman football player and roommate. He studied for a marketing degree and began pursuing hip-hop. He lined his apartment closet with Styrofoam as a makeshift vocal booth, where he rhymed into a tiny lavalier mic clipped to a hoodie on a clothes hanger. He cut his first track to Jay-Z’s “Feelin’ It.”

After college, the working world: He tried selling cars for a few months and discovered he hated it, yet the dealership carved out a niche for him as utility support staff. He worked as an assistant grocery store manager. Like his dad decades ago, Weathers works as a bartender (Wooly’s, ’85 Bar).

His first step toward nonprofit work began several years ago with a simple favor to a friend who knew teacher Stacey Robles at Capital View Elementary, who asked him to speak to students about music.

Soon he agreed to supervise students during early mornings before school as they played basketball and goofed around in the gym. In the fall of 2019 he and his DeadStock Entertainment collective of music and visual artists raised thousands of dollars for coats for students at Jackson Elementary.

As Weathers’ threads of music, outreach and activism wove together, they culminated with the July 27, 2020, incorporation of the B.WELL Foundation to further the “development and expansion of young minds by building character through mentorship and education.”

Part of what Weathers began to realize in adulthood was how much he had craved other mentors as a boy—mentors who remained scarce outside of his own family. And the middle school years are what Rogers, now also foundation president, called “those vital years” for benevolent guidance.

“Once you come out of eighth grade it’s almost kind of predetermined in a way which kind of direction you’re going to go from there,” Rogers says.

The Des Moines Education Association in September named Weathers its Volunteer of the Year. During the holidays the foundation staged Operation Wishlist, providing $200 grants to 91 families across five middle schools.

Weathers hosted a 3-on-3 hoops tournament for area youths last October at Evelyn K. Davis Park. Local artists and other nonprofits also participated in the event.

The local civil rights debate escalated alongside Weathers’ nonprofit career. One marker was the Iowa Legislature’s unanimous passage on June 11 of a criminal justice reform bill partially banning chokeholds and enabling greater prosecution of police misconduct.

Weathers says that while 2020 shined a spotlight on America’s racial issues, it certainly didn’t answer all his questions. He remains stymied about “why 244 years of free labor has created the American socioeconomic system. Why Blacks are just so demonized.”

“I’m never going to stop fighting,” he says, “but the system in which I’m fighting is not made to be fixed.”

So he works toward practical progress, based out of a house on the city’s north side, along the Sixth Avenue corridor, that he shares with five friends. His office is nearly a terrarium full of bamboo and other houseplants, all organized around a desk with his laptop computer, a pair of speakers and a microphone stand.

He’s preparing the release of a new and more introspective album, simply titled “Billy.” Most of it was written before the pandemic. Its vulnerability and “sadder tone” are a byproduct of Weathers, on the verge of age 30, wrestling with his decision to pursue his music career at the expense of a more conventional family life.

The escalation of his philanthropy and activism in 2020 added yet another complex layer. For instance, Weathers drew as much criticism as praise for locking arms with the Iowa State Patrol at the Terrace Hill protest. He operates in the middle ground, calling himself a mellow person who believes in the power of collective change. But operating at the center of controversy to build alliances can leave people like Weathers vulnerable to criticism from all directions. It’s hard work to build and maintain trust among people who try to collaborate despite their diverging views. It demands everybody’s time and integrity.

Rose, a conservative Republican, realizes he doesn’t always see eye to eye with the protesters whom he’s helped to amplify. But he’s confident that “Billy’s going to be one of those guys that I’m probably going to watch the rest of my life.”

If similar connections are being made in other cities, if other nonprofits such as his rise up, maybe this will be one of the bright silver linings to emerge from 2020.

Iowa State Rep. Ako Abdul-Samad, 69, was prominently featured in news coverage last year as a peacemaker on the front lines of Des Moines protests, helping to hold together a loose coalition of leaders from Black Lives Matter/Black Liberation Movement and other groups. Weathers and his peers increasingly will need to take on that mantle.

As Weathers put it on Instagram, “To my core, I believe you can change the world by being a walking testament of what you stand for—and that’s all I want to do.”

His final words to the May 29 rally: “Nothing ends here. It all begins here.”

He’s already been proved right.