Editor’s Note: This story was included in the list of our favorite 2020 print stories. For reference, it was published in July 2020.

Writer: Wini Moranville

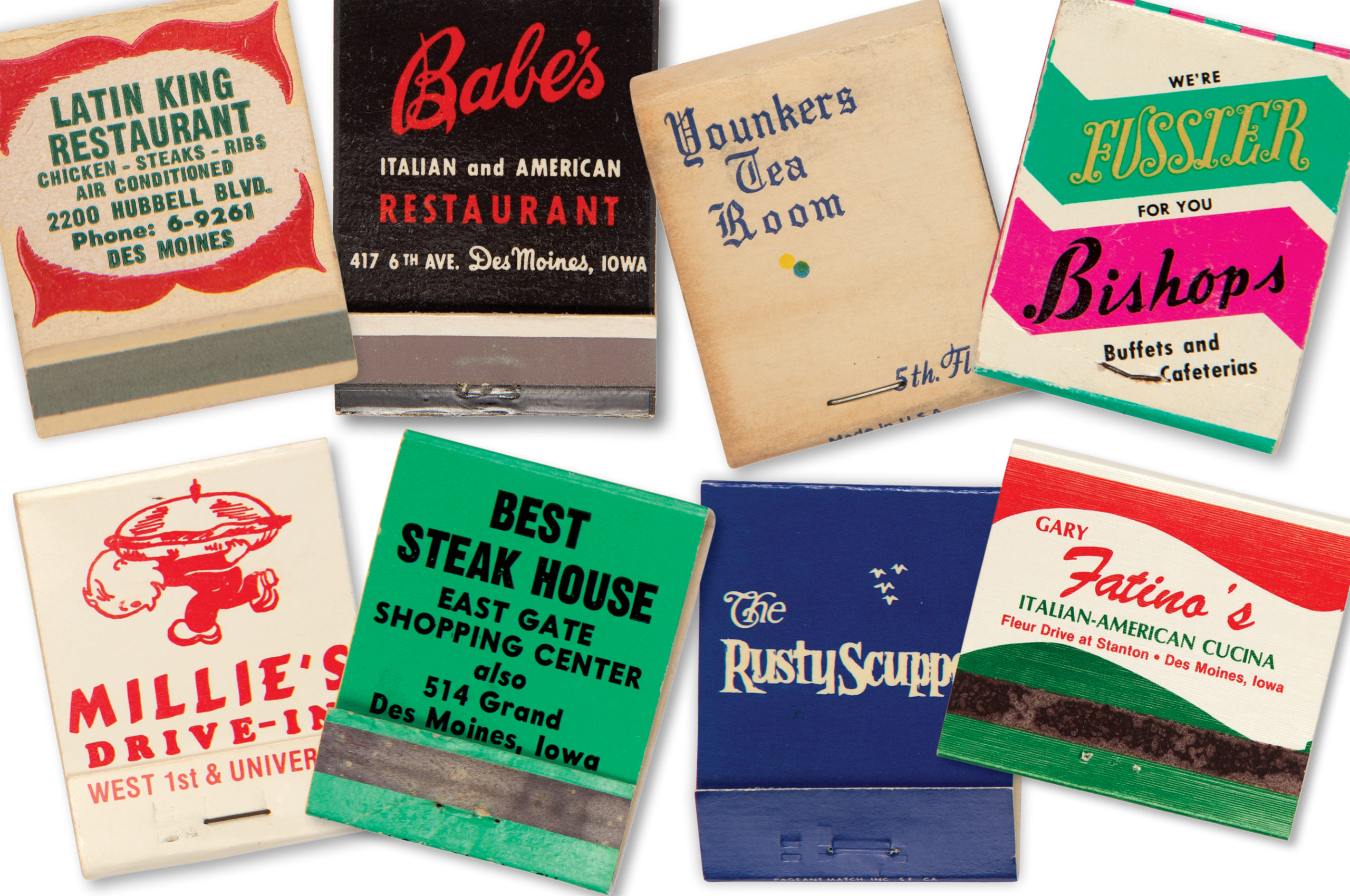

Special Thanks: George Formaro for the Matchbook Collection

Sometime in the summer of 1980, while I was waiting tables at the Younkers Meadowlark Room in Merle Hay Mall, a rotund 30-something man and two young women were seated in my section minutes before closing time. Because the restaurant was almost empty at this hour, the trio had my undivided attention, which is why I noticed something odd: As he walked around our extensive salad bar, the man was jotting down notes in a little oblong notebook.

After the polite but reserved party left, I conferred with the cashier: Sure enough, the name on the credit card receipt was Richard Somerville, who was at the time the Des Moines Tribune’s restaurant critic, then known as the “Grumpy Gourmet.”

Two anxious weeks later, the review appeared in the afternoon paper. His verdict? A disappointing three out of five stars.

“Just about everything at the Meadowlark Room is classy,” he wrote. “Everything, that is, except the food.”

He told of a chicken cordon bleu topped with something akin to a thick, yellow sauce he last saw at the Hi-Ho Grill. Bits of gristle marred the chicken crepe’s filling, and the prime rib was well past the medium-rare doneness requested.

That he deemed his server (me) “very attentive and cheerful” did little to assuage how flattened we all were by his review. The sous-chef who’d overseen the kitchen the night of the critic’s visit—usually one proud, swaggering dude—could hardly look the rest of us in the eye.

Over the next few days, the responses among the management and staff progressed from “how dare he say such cruel things?” to “how can we do a better job tomorrow?”

The question in my mind, however, was, “How do I get that guy’s gig?”

Had I taken on restaurant reviewing in 1980, I would have spent the next few years covering steakhouses, red-sauce spaghetti joints, cafeterias, diners and just a handful of fancy chandeliered restaurants with tuxedoed maitre d’s.

And I would have thought it was grand.

Some days, I would have headed to casual coffee shops and cafeterias for well-crafted everyday food. Reviewing Baker’s Cafeteria, I would have reveled in the crisp fried chicken livers, the homemade chicken gravy, and meringue-topped raisin-cream pie. I would have gladly tucked into the plank of fried sole and some French silk pie at Bishop’s, hot roast beef sandwiches at DeCarlo’s and chicken-fried steak at the Hi-Ho Grill.

I would have praised Younker’s Tea Room and its outposts the Meadowlark Room and the Peacock Room not only for their famed rarebit burgers, sticky rolls and classic chicken salad, but with an admittedly biased insider’s view:

I knew that everything from the daily soups to the ice cream were made in-house. That wee bit of gristle in Mr. Somerville’s crepe was indeed a flaw, but it attested to the way the meat was cooked fresh and plucked from the bone every day.

At the great Italian-American steakhouses, such as Gino’s, Imperial House and Johnny’s Vet’s Club, I would have loved questing for the perfect thin-sliced onion rings—so hot they burn your fingers, so crispy they flake all over your shirt, and just so soft, slithery and sweet inside.

I would have applauded ice-cold gin gimlets, prime rib and steaks nailed a perfect medium-rare, zippy red-sauced pasta with hot, fennel-enhanced Italian sausage, and yeasty homemade dinner rolls. I would have felt so sophisticated, ordering Pink Squirrels and Golden Cadillacs and other pastel-colored

ice-cream drinks.

But when it came to the city’s high-end dining, I would have hardly been able to believe my good fortune: duck à l’orange flambéed tableside at Ducks and Company, lobster at the Pier, Steak Diane with Gratin Dauphinoise at Quenelles, Champagne brunch with eggs benedict and petits fours at the Crystal Tree. Sitting in a plush half-moon booth at Guido’s, I would have watched as Guido himself carved my prime rib from a tableside cart.

Would I have grown weary of having to choose between diners, spaghetti joints, steakhouses or continental fare? Heavens, no. Besides, I would not have known what else to look for.

But I did not snag the Grumpy Gourmet job in 1980. Instead, I moved to New York City. Then England. And then Ann Arbor.

Those years in exciting elsewheres opened my eyes and palate to a wide world of food, from the Middle Eastern venues on Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue to London’s Indian and Malaysian restaurants. I discovered sushi at a spot in the shadow of the Empire State Building, a proper cappuccino at Caffe Dante in the Village, foldable thin-crust pizza in Brooklyn. At Zingerman’s Deli in Ann Arbor, I learned just how crazy-good chopped liver and corned beef tasted together in a sandwich. Though I sometimes missed Midwestern cooking, I soon gleaned an appreciation for fresh seafood and a lighter, brighter side of Italian and French cooking, for vinaigrettes and mesclun. Homemade pasta. Fresh cilantro.

As it happened, 17 years after waiting on the Grumpy Gourmet, I finally did get his gig.

I moved back to Des Moines in 1991; soon after, I fused my ongoing love for food with my experience in publishing to launch a career as a freelance food writer and editor. Later, in 1997, the Register’s restaurant reviewing gig opened up; I tried out and snagged the job. With the Tribune long gone, the column now ran in the Des Moines Register and was called “The Datebook Diner.”

At first, I worried that my far-flung dining experiences might not serve me so well. In addition to all that worldly eating in the ’80s, by the ’90s I’d begun spending long stretches of each summer in France. While I’ll always admire a great steak and an icy-cold gimlet, I also knew there could be more to a city’s dining life than what we already had.

The full parking lots and long waitlists at some of the so-so restaurants I reviewed led me to believe that Des Moines diners seemed pretty happy with the way things were—did anyone really want me to point out that they could be better? Des Moines hates a snob; the city could not care less how things are done in New York, much less the South of France. As I began to find my voice as a reviewer, I struggled between being a cheerleader for the status quo and saying what I really thought.

I didn’t have to struggle all that long.

Just a few months after I penned my first review, Bistro 43 opened in Beaverdale. Jeremy Morrow started serving chef-driven, local, seasonal cuisine from the bustling open kitchen amid a delightfully unstuffy decor in an old brick neighborhood storefront. He was among the first to tell us—smack-dab on the menu—where our food came from, putting words like Cleverley Farms greens and Eden Farms Berkshire Pork into our city’s culinary vocabulary.

To be sure, previous restaurants had also tried to similarly energize the scene, but Bistro 43 was the first to do so with any staying power on my watch. Other innovative, fresh-focused restaurants popped up alongside and soon after. The successful runs of Carpe Diem, Brix, Danielle, Corner Cafe, Bistro Montage and Sage confirmed that Des Moines was hungry for more innovative styles of dining; the standards had been raised. Soon, I stopped having to define words like chef-driven, heirloom and artisanal in my reviews.

During my 15-year stint as the Datebook Diner and later, as I’ve covered the scene for dsm, our restaurants improved in so many ways, both seismic and small. Early in the 2000s, I nipped into the Wine Experience, where a teenager behind the cheese counter astounded me with an almost frenzied knowledge and enthusiasm as he regaled me with samples. C.J. Bienert was just out of high school when he started cheesemongering, but already he was well on his way to becoming this city’s champion for all things artisanal, later moving to Gateway Market, then progressively opening his own always-buzzing spots, the Cheese Shop and later the Cheese Bar.

While I still loved Gino’s and Noah’s and Latin King for what they did best, it was exciting to see newer restaurateurs in the genre nudging diners off the beaten path. Jerry Talerico of Sam & Gabe’s showed us a more fine-tuned style of Italian-American supper-club cuisine, while Steve Logsdon at Lucca hit his stride by looking to Italy’s north for inspiration.

Centro beckoned us all back downtown, throwing a great party night after night, with everyone invited in for as little as the price of a pizza. Americana and Django also helped usher in a rebirth of our city’s core, with other hot spots to follow.

Coffeehouses, craft cocktails, signature desserts—all have flourished in the 20-plus years I’ve enjoyed my front-row seat. Pizza got more exciting thanks to Gusto, sushi became more daring, and the barbecue scene exploded. Spots like Thai Flavors and Tacos Marianas helped us discover a fresher and more vivid side of Southeast Asian and Mexican cuisines.

As new beer connoisseurs sought something as well-crafted as the brews in their glass, Full Court Press restaurants (Royal Mile, Fong’s, Truman’s Pizza Tavern, Iowa Taproom, et al.), Cheese Bar, Lua Brewing and others have stepped up to the plate.

To be sure, it hasn’t been all Bistro 43 and Sage, great cheese and Jerry Talerico’s cannelloni. I dined through a slew of lackluster sports-bar meals; I sat through some lifeless hotel dining. My heart often broke for the also-ran venues that aimed high, but for whatever reason just couldn’t pull it off. I witnessed once-greats like Younkers Tea Room, Crystal Tree and Quenelles hang on by a thread, all but giving up until they finally did.

And yet, for each good thing that came to an end, something else would emerge. We may have lost our last department store dining room, but cafes at the Art Center and Botanical Garden have hit their stride. Saying goodbye to favorites—Bistro 43, Sage, Bistro Montage and the like—was hard, but Alba, Harbinger, Table 128, Splash, Aposto, Proof and others continued to give us plenty to love.

Oh, Des Moines, it’s been a great run, hasn’t it?

As I write this, our city’s restaurants are starting to reopen; a few have closed permanently, and I fear more difficult news will come. Restaurateurs have told me that in the aftermath of this pandemic, our dining scene will have changed in ways they can’t yet foresee.

What’s next, no one can say for sure. Yet this is an ode, not an elegy.

As I try to envision what it will all be like when our restaurants reopen, I think back to an article I wrote in 1999 when I was asked for predictions on Des Moines dining in the new millennium. I was optimistic, but I reminded diners that we all had a role to play. I wrote: “A city gets the restaurants it deserves, the restaurants it will support.”

That’s always been true, but it’s never been more urgently true than now. The restaurateurs that pull through will do so by being flexible, creative and resilient, by rolling the dice on untested approaches, and by working even harder than they did before. If we expect a city of great restaurants, it will be on us to show up—with gratitude and in full force.