Writer: Barbara Dietrich Boose

Photographer: Ben Easter

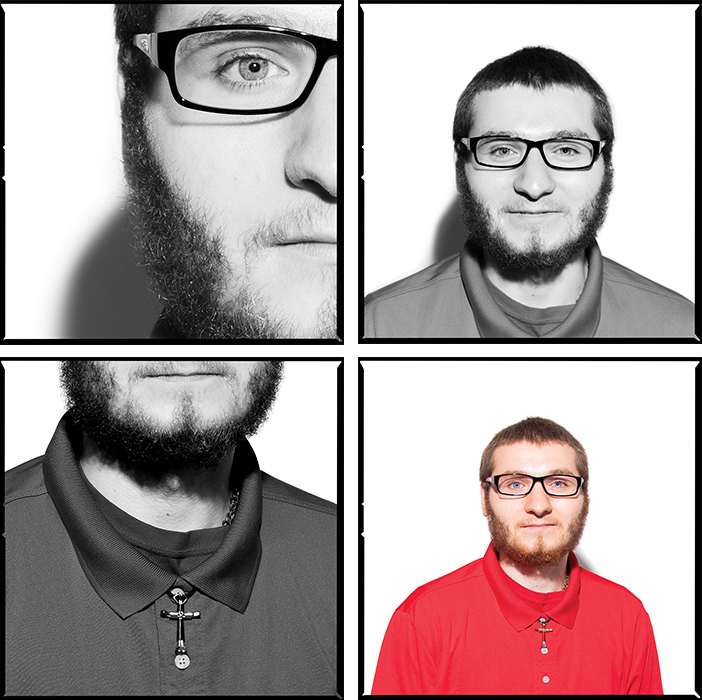

Michael was a teenager in a middle-class family in Des Moines when his parents decided to divorce. Things got rocky for Michael at home and school, so he ran away.

“It was a bad decision,” he says. He moved into a trailer park with his sister, who’d gotten involved in sex trafficking. That led the Iowa Department of Human Services to eventually declare him a “child in need of assistance,” after which he spent time in a mental health care institution and at Orchard Place, a Des Moines-based organization that provides mental health treatment and services to youths.

Later, homeless, he was arrested for “street preaching.”

When the police learned about his situation, they connected him with Iowa Homeless Youth Centers (IHYC), a program of Youth and Shelter Services (YSS) that works with individuals ages 16 to 22 and parents ages 16 to 25 to become self-sufficient and plan for a successful future.

Now in rent-assisted Section 8 housing, provided to low-income people through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Michael, 23, is working to help young people in Polk County avoid the homelessness he experienced. He is a member of the Youth Action Council, made up of about 50 individuals who experienced homelessness when they were younger than age 24.

The council is part of a major effort facilitated by the Youth Policy Institute of Iowa to end youth homelessness in Des Moines and Polk County; last fall, that effort paid off in the form of a two-year $1.8 million HUD grant to the city.

“As Gandhi said, we have to be the change we want to see,” says Michael, who requested his last name not be used in this article. “We can come together and make the world a better place.”

Michael, who didn’t want his last name used in this story, was homeless as a teen and is now a member of the Youth Action Council, made up of about 50 individuals who experienced homelessness when they were younger than age 24.

Coordinated Effort

A variety of service organizations have worked to help homeless youths in Polk County, but their efforts became more broad-based, coordinated and strategic in 2017, when more than 50 stakeholders from 35 public and private organizations and more than 50 youths ages 15 to 24 began to discuss the issue. Staff from YSS-IHYC and the Youth Policy Institute of Iowa facilitated the meetings, supported by a grant from the Mid-Iowa Health Foundation.

“There was a growing desire among many who are on the front lines … to develop a better approach,” says Suzanne Mineck, president of the foundation. “An impressive number of organizations and community advocates just showed up to learn, listen and share, and then develop a plan.”

The city of Des Moines and the Polk County Continuum of Care Board, which is charged with creating a community response to homelessness through policy, programs and services, twice applied for grants from HUD’s Youth Homelessness Demonstration Program (YHDP). This grant program is designed to help communities build a wide range of services, including rapid rehousing, permanent supportive housing and transitional housing. The city’s third time applying was the charm, when in August 2019, Des Moines was named one of 23 communities to receive YHDP grants totaling $75 million.

Angie Arthur, executive director of the Polk County Continuum of Care, says the two years of collaboration among stakeholders that began in 2017, including creation of the Youth Action Council, were key in landing the grant. “We had done a lot of community work, including with the Iowa Department of Human Services, the schools, the juvenile justice system and service providers, and we were able to build on that,” she says. “It’s been an exciting opportunity for the community to come together and to have youth engagement at a high level.”

By mid-June, a steering committee of YHDP stakeholders had worked via Zoom meetings and other virtual communications, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, to select five nonprofit organizations to receive the HUD grant money. As of press time, the organizations were set to begin implementation of their proposals this fall.

“Through this grant, we’re creating a communitywide approach to serving young people in innovative ways with the goal of youth homelessness becoming a rare, brief and nonrecurring experience,” Arthur said in the grant announcement.

Making Progress

Youth Action Council member Katrina Knox, 20, was homeless in Des Moines for a year and a half, including a winter she lived in the back of a U-Haul trailer. She says she “fell in with the wrong crowd” and “got hooked on drugs and alcohol.” Now living with her mother and a year sober, she’s parenting three young children, managing some health issues and planning to pursue criminal justice or forensic pathology, having been accepted at Des Moines Area Community College.

“I was a little bit scared during my first council meeting, because when I first meet people, I’m shy, and I don’t do well in big crowds,” she says. “But serving on the council has been great, because I want to help people. A lot of people don’t understand what it’s like being 16, 17 or 18 and living on the street, but I’ve been in those shoes.”

The Des Moines-based Youth Emergency Services & Shelter of Iowa is the state’s largest and most comprehensive emergency shelter for kids and supports more than 800 children, newborn through age 17, per year. Children under age 13 who become homeless may end up with their families in a shelter, hotel or temporary housing; living with extended family members; doubled-up in homes with other families; or placed in foster care.

But older youths experiencing homelessness are more likely to fall below the radar. They may be couch-surfing at friends’ homes or living in a homeless camp or abandoned building and yet somehow managing to get to school, disguising their situation. Some in foster care become homeless after “aging out” of the system at 18. Many Polk County stakeholders hope the HUD grant will benefit these individuals.

“We don’t get much federal funding for homelessness services for minors and 18- to 24-year-olds. The reasons and solutions for those youth facing homelessness are different from those of adults, so the strategies have to be different,” says Andrea Dencklau, senior policy associate at the Youth Policy Institute of Iowa. “People often forget that among young people who experience homelessness, so many have been through real, significant trauma. We don’t always know how to respond to adolescence.”

Katrina Knox was homeless for a year and a half: “A lot of people don’t understand what it’s like being 16, 17 or 18 and living on the street, but I’ve been in those shoes.”

A Place ‘To Hang Out’

There are as many reasons for homelessness as there are the number of people experiencing it. But whatever the reason, homelessness is especially dangerous for youths who are vulnerable, economically dependent and still developing intellectually, emotionally and socially. YSS’ Iowa Homeless Youth Centers, Central Iowa’s primary provider of services for homeless youths ages 17-24, focuses on helping them overcome those hardships.

The organization operates two transitional housing programs, one specifically for pregnant and parenting youths. In 2016, Iowa Homeless Youth Centers opened the Youth Opportunity Center at 612 Locust St., which offers “a safe place for youth 16 and older to hang out and be teens,” says program manager Elizabeth Patten.

Before the pandemic hit, the center was open noon to 6 p.m. for youths to use its TV lounge, laundry facility, art studio, game area, computer lab and dining area, where they could help prepare and have lunch and dinner, Monday through Friday.

As of press time, that “drop-in” component was still closed because of COVID-19, but youths can stop by to pick up donated clothing, hygiene supplies and to-go meals. Staff members also have maintained mobile outreach efforts, circulating throughout the city’s homeless camps, parking lots, laundromats and other 24-hour facilities to connect with those who need help.

“From the beginning of the pandemic, our goal was to identify current gaps in services for youths at risk or currently experiencing homelessness and to create solutions to meet these needs, while taking into account the safety of all members,” says Patten, who adds the organization hopes to reopen the center in late fall with abbreviated hours and other protocols in place, but “nothing is set in stone.”

Virtual Programs

Iowa Homeless Youth Centers’ programs such as rapid rehousing and mental health counseling have continued virtually during the pandemic. Its rapid rehousing programs work to find housing for individuals referred by Primary Health Care, the nonprofit organization that manages Polk County’s centralized intake process that determines options for individuals and families experiencing homelessness. In addition, the Youth Opportunity Center offers emergency beds for 30 days to referred individuals ages 18 to 24. The staff screens these clients daily for COVID-19 symptoms.

Clients can remain longer than 30 days if they opt to work with a staff member to develop a case plan. “All case management is client-led and based on whatever they want to work on–education, employment, etc.,” Patten says. “We work really hard to build rapport with youth. Our goal is that no matter when they come, there’s a staff member here who can help them with what they need.”

Patten praises all the stakeholders who continue working on the HUD program, including members of the Youth Action Council. “They brought such a good perspective and … deserve that support and leadership opportunity.

“We’re asking so much of them,” she adds. “Most of the council members are still homeless, and they know the impact of the HUD grant is likely not going to affect them. But their goal is to make it better for those who follow.”

The grant also is important for all who are engaged in the heavy lifting of reducing homelessness. The work is “really rewarding but also so painful,” Patten says. “This project is a big burnout reducer. It shows this community is willing to step up.”

That is invaluable for the community itself, says Abbey Barrow, youth homelessness demonstration program coordinator with the Polk County Continuum of Care. “This is our next generation of leaders,” she says. “If we don’t provide them with the services and support to grow, our community won’t be able to thrive or be the community we want it to be.”

Recipients of the HUD Grant and how the money will be used:

Anawim Housing: $375,464 for housing for young people with disabilities.

Children and Families of Iowa: $364,618 for transitional housing and rapid rehousing for youths who have experienced domestic violence.

Institute for Community Alliances: $74,940 for Homelessness Information Management System data work to manage grants.

Iowa Homeless Youth Centers: $304,178 for mental health and drop-in services and $527,448 for a rapid rehousing program.

Primary Health Care: $162,446 for a youth housing navigator position.

Seeking to Make a Difference

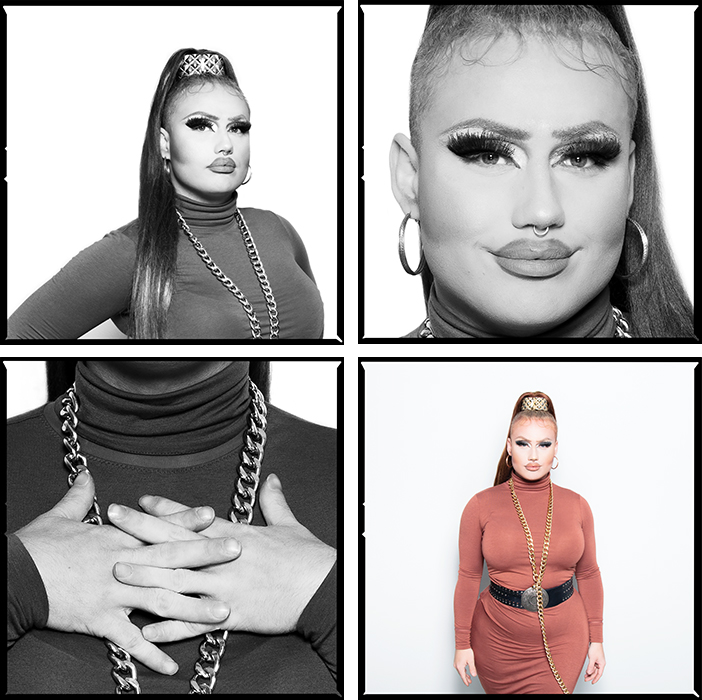

Jade exudes affability while showing off colorful posters made for friends in the art studio of the Youth Opportunity Center at 612 Locust St. A 24-year-old who prefers the pronouns “they, them and their,” Jade as a youth experienced gender dysphoria—a conflict between a person’s physical or assigned gender and the gender with which he/she/they identify—and depression.

After losing a job at a Fort Dodge hotel and breaking up with a partner, Jade moved to Des Moines and eventually ended up at Central Iowa Shelter and Services and then in a homeless camp, where the nonprofit organization Joppa provided tents. A group of bikers brought sandwiches, and a nearby company allowed campers to use its outdoor water hose.

“There are so many organizations helping the homeless, it’s beautiful,” says Jade, who requested their last name not be used. “They need credit.”

But homelessness is ugly. Jade knew Charles Childs, a homeless man who was robbed, murdered and left in a homeless camp. Police then cleared out the camp, so Jade lived in an abandoned building overrun by feral cats: “I was scared. … I thought, ‘I don’t belong here.’ ”

Performing in drag shows at the Garden Nightclub and Blazing Saddle, two Des Moines gay bars, helped change Jade’s life. Lip-syncing as “Barbie D” to songs by Beyoncé in a blond wig and 4-inch heels, Jade says, is “invigorating and soul-uplifting” as well as a source of income.

Jade, who prefers the pronouns “they, their, them,” is confident the Youth Action Council will create positive change: “I see great potential in our work.”

Another life-changing event was when Jade was referred for one of the nine emergency beds at the Iowa Homeless Youth Centers’ Youth Opportunity Center: “The first night I was there, I slept harder than I’d ever slept in my life. It was a transcendent moment.”

In addition to shelter, the center connects Jade with a social worker, and staff members helped Jade obtain a birth certificate, identification card and Social Security card. They also invited Jade to join the Youth Action Council, part of the Des Moines/Polk County Youth Homelessness Demonstration Project. In that role, Jade has participated in brainstorming on solutions for homelessness, discussed the issue with state legislators at the Capitol, and joined fellow council members in speaking to a sociology class on homelessness at Drake University.

“I am super-excited about this. The reward for me is that I’m convinced this will make a positive change,” Jade says. “There are so many aspects to the issue–not just homelessness, but also needed supports for LGBTQ youth, the effects of racism, foster-care and after-care problems, and services for foreign-language speakers. But I see great potential in our work.

“If I could say anything to anyone who is homeless or on the verge, it would be, do not lose the flame inside of you. That will light the way for you,” Jade adds. “The hardest thing to do is love yourself and to ask for help. Reach out to the programs that can help you. You are not alone.”