Multifaceted artist Andre Davis uses poetry and music to speak out on social justice issues. “The beautiful thing about art is it can get people to stop and to look at what’s happening around them,” he says. Photographer: Janae Gray.

Art in all its forms—music, film, literature, theater, photography, painting and more—can provide entertainment, give comfort and inspire joy. But works of art also can challenge perceptions and incite change. Activist artists seek to use their talents and creativity to shine a light on issues they care about, blurring the line between who they are as a creator and as a citizen.

Throughout history, artists have confronted the prevailing political, social and cultural power structures. For example, Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel, “The Jungle,” exposed the meatpacking industry’s exploitive labor practices and unsanitary conditions; artist Jacob Lawrence’s 60-panel painting called “The Migration Series” portrays the turmoil Black Americans experienced moving from the rural South to the urban North during the Great Migration; Diego Rodriguez’s political murals throughout Mexico in the 1920s protested the ruling class.

Today’s artists continue to challenge the status quo. Over the past decade, Des Moines-based Jordan Weber, for instance, has gained national acclaim for his multimedia works, sculptures and installations focusing on social justice issues and historical and current events.

Modern-day platforms—websites, blogs, social media channels—give artists ways to showcase their work, make their messages accessible, and reach more people directly than they could in the past. On the following pages, meet three up-and-coming 20-something artists who are showing us new ways of seeing the world—and our place within it.

Andre Davis

Becoming a Modern-Day Warrior

Writer: Christine Riccelli

Photographer: Janae Gray

As a 16-year-old high school freshman in St. Louis, Andre Davis was roller skating with an uncle and a few friends in a neighborhood parking lot when the police showed up and told them to leave.

They started walking back home, “but the police just kept harassing us all [along the way]. They threw us on the concrete and said, ‘You got guns in your skates. You got drugs in your skates.’ We said, ‘No, we just came from the very place you told us to leave.’

“Seeing my uncle afraid made me afraid, and not knowing how to respond to it in the moment frustrated me. It didn’t sit well. … I thought, ‘Who are the folks who would fight for people like us?’ ”

Davis, now 27, came to understand that he could be the answer to that question, a realization that has spurred his creativity and driven him as a hip-hop artist and poet. “The beautiful thing about art is it can get people to stop and to look at what’s happening around them,” says Davis, also a 2021 Drake University Law School graduate.

Growing Recognition

Over the past few years, Davis has gained increasing recognition as a multifaceted performer and artist. He performed last year at the Riverview Music Festival and at Iowa Public Radio’s 2021 Juneteenth concert at xBk. In 2018, his first album was produced through Station 1 Records, a local nonprofit recording label.

He’s also released singles, including the powerful “Fight On” in 2020, a response to the murder of George Floyd, and “Andre’s Prayer (God Can You Hear Me),” an evocative, plaintive piece he’s called “my last conversation between God and the universe.” (To hear him perform both pieces at the Juneteenth concert, scan the QR code on page 112.) At press time, “Sacred Assassins,” a four-track EP he’s creating with local hip-hop artist and collaborator DK Imamu Akachi, was expected to be out this summer.

Looking Inward

Davis hopes his work helps listeners become aware of not only what’s happening around them but also inside of them. “Fighting doesn’t always have to be out in the streets,” he says. “Look into yourself and really answer the question: What do you align with? What are you willing to fight for? We all have conflicts we have to face.

“What I’m trying to encourage people with my art is: Don’t let the problems of the world or in yourself sit there until they become so big that they engulf you. Look them in the eyes.”

That’s a lesson he learned living in an area “where there was a lot of violence and brutality. … Growing up, I spent a lot of time expressing myself in art, dance and poetry. But I got into a lot of fights as well,” he says. “So at a young age it became clear to me that expressing myself with something [positive] is important, but there’s still a level of aggression there as well.”

His neighborhood environment and experiences led him to develop what he calls a “warrior’s spirit. Throughout history, warriors used swords and shields. I guess I’m a modern-day warrior using a pen and pad and microphone.”

His other warrior tool: the law. “When I was 7, I remember telling myself, ‘I’m going to be the first Black president and I’m going to be a lawyer,’ ” he recalls.

“We all know how the first one turned out,” he adds with a laugh.

Drake University recruited Davis as an undergraduate. After earning a degree in law, politics and society in 2017, he decided to take a year off to get to know the city better. “I wanted to connect with people and see what was really going on outside of campus,” he says, adding he was surprised and pleased to discover the local cultural community was welcoming and collaborative, unlike the more competitive St. Louis arts scene.

So Davis chose to stay here to attend Drake Law School, graduating in 2021. His long-term goal is to open a corporate law firm that specializes in helping small Black companies structure and position their business for success in low-income areas. Growing up, “I noticed that violence wouldn’t happen in areas where there were [thriving] businesses,” he says.

With a vibrant neighborhood business environment, people “wouldn’t feel the need to resort to other avenues of obtaining money or other avenues of revenge after getting harassed by police officers after a night of skating,” he adds.

While much of Davis’ hip-hop work has had an activist bent, he’s also created more personal pieces. His 2018 EP, “Poetry Jazz Sessions,” includes a poignant poem in tribute to his late grandmother. “One of the people who helped me fall in love with music was my grandmother,” Davis recalls.

“She was a huge Michael Jackson fan,” he adds. “She’d be sweeping the kitchen floor and playing [Jackson’s] music. That would always be [when] she would tell us about life. She’d always say, ‘Live your life with purpose. Don’t be out here just taking anything from anybody. Be true to yourself.’”

That lesson has evidently stuck. “When I think of the long term, my goal is essentially to live life in the way that feels most aligned with who I am as a person,” Davis says. “I think if you can get to a space where you go, ‘I’m not going to fight myself anymore. I’m just going to exist as truthfully as I can’—I think that’s more than enough for anybody.”

Speaking to the messiah,

almighty provider

I’m asking about what happened

with my experience prior

my baptism by fire,

forged to be the iron-

sword to fight the wars for all the children of Zion

praying that I’m maintaining

a certain sense of refinement

trying to be enlightened

while also seeking alignment

—Excerpted from “Andre’s Prayer” by Andre Davis

Hannah Soyer

Empowering the Disability Community

Writer: Hannah Soyer

Photographer: Mary Mathis

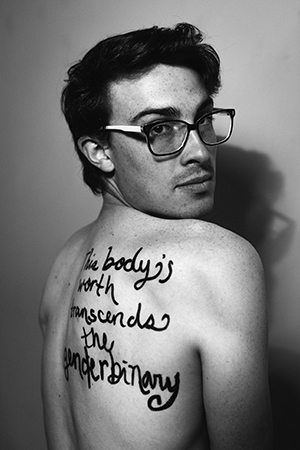

I’m in my apartment in Iowa City, blinds drawn, the only light coming from the spotlight my photographer friend Mary Mathis brought with her. Another friend has just finished writing the words “THIS BODY IS WORTHY” in marker across various parts of my body that I am self-conscious of: my back (which has a scar running from the top to the base, and is misshapen), my chest (which is barrel-shaped), and my feet (which curl under). I am sitting in my power wheelchair. “Look down and to the side,” Mary says from her crouch in front of me, and pushes the shutter button on her camera. This was the beginning of This Body is Worthy, a project of mine which would grow over the coming years.

I had just finished my final year as an undergrad at the University of Iowa. As a woman with a visible disability, I had spent 22 years living in a body that society had told me time and time again needed to be fixed, hidden or shoved aside. The constant presence of these beliefs—from others and from myself—exhausted me. I was ready to change that.

Seeing my own body captured in the frame of a camera, with these words marching boldly across my skin, can only be described as liberating. There is a special power to the word worthy—it is not determined or related to appearance, productivity or ability. It is an unconditional term, and it is all-encompassing. Worthy of love? Yes. Worthy of respect? Yes. Worthy of attention? Yes. Worthy of stories that celebrate difference and health care that upholds peoples’ dignity? Yes, and yes.

The experience of viewing my own photos was too powerful to keep solely to myself––with the help of Mary and a few more friends, I held my first This Body is Worthy community workshop a few months later. We invited anyone who felt that their bodies were outside of mainstream societal ideals to come, write a phrase on their body professing its worth, and have their photo taken. I quickly realized that the act of declaring an aspect of one’s body as valuable and worthy is one that benefits every single person. The photos and statements that came from the community workshops were joyful and radiant—participants presented themselves in ways that they wanted to be seen, and how they wanted to see themselves.

I moved to Kansas for graduate school in 2018, and any time to hold more community art workshops quickly disappeared under coursework and my teaching load. Still, I wanted This Body is Worthy to continue, and I wanted it to reach further audiences. I decided to make shirts and then other merchandise through the website Threadless. This Body is Worthy now sells designs exclusively from disabled artists, with all proceeds going directly to organizations led by and for disabled people, and the artist.

This building of and commitment to the disability community is something I dove into again with a series of Zoom writing workshops I held in the summer of 2020, specifically for creators with disabilities. I would eventually name this series Words of Reclamation, to speak to the power that words have in shaping our identities, our beliefs and our perceptions of the world (words like worthy, for example). These four workshops, held over the course of a week, were especially powerful given the time they were held—just a few months into the COVID-19 pandemic, but already at a juncture where the devaluing and disrespect toward disabled life were running rampant through our world. These workshops created a space where we could both mourn and create, together. The art that came out of this series gave voice to the simultaneous hurt and love that we were feeling at this time.

To me, arts activism entails the transformation of both our inner and outer worlds. My This Body is Worthy photos allowed me to perceive differently, which then spurred a movement. Words of Reclamation incubated disabled creatives, empowering us to value our own voices and the voices of our peers, while also giving birth to writing that demanded the attention of nondisabled readers.

When I was at the University of Iowa, a fellow English major gave a presentation to our class on what made her invested in the humanities. “Literature and art are what make us feel,” she said. Of course this is true—the power of a story or experience (portrayed through any medium) to unstop the plug in our emotions is no small thing. The ancient Greeks used katharos (today’s “catharsis”) to describe the emotional release that happens when audiences view a particularly poignant theater performance. But it’s more than this, too: The power of art as a tool for change isn’t just that it makes us feel, but that it shakes up our perceptions and delivers us new ways of seeing our world.

Photos from This Body is Worthy.

Jo Allen

Creating a Safe Space

Photographer: Anthony Arroyo

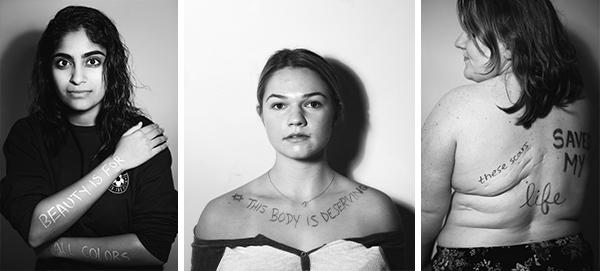

Jo Allen is a nonbinary photographer who launched Jovisuals last fall. In addition to running the photography business, Allen organized the rally in support of transgender rights that took place at the state Capitol in early April. Allen also spearheaded a fellowship program for this year’s 80/35 Music Festival through which photographers ages 16-21 will have the opportunity to shoot the event and have their work published. A 24-year-old Des Moines native who graduated from Iowa State University in 2021 with a degree in journalism, Allen spoke to dsm about their journey and how they hope their photography can make a difference in the lives of LGBTQ individuals and those in other underrepresented communities.

What led you to start Jovisuals?

Growing up black and queer in Iowa, I didn’t see any representation of people like me anywhere—not in the media, not in school, not in government, not in any spaces I existed in. If you come from an identity that isn’t white, you just don’t see yourself. Once I left that space and recognized the value, beauty and power in being visible, I was able to direct my photography toward uplifting others. I work primarily with folks in the LGBTQIA+ community, but also with people of color and anyone with a marginalized identify.

In an essay you wrote for one of dsm’s sister publications, the Business Record’s Fearless, you shared your story of being diagnosed with and treated for stage 4 non-Hodgkin’s Burkitt lymphoma in 2016 when you were 18. How did that experience shape the work you do today?

I actually started cultivating the idea for Jovisuals when I was battling cancer. That life-and-death situation was the turning point for me. I was thinking, “What about other kids who have cancer or other life-changing health issues? Where are they?”

Then that idea started to sprout into something else that eventually became Jovisuals. Being on my deathbed made me realize I would never go back to suppressing who I was and who I wanted to be. I kept thinking to myself, why would you hide who you are for the rest of your life?

And I decided that I was also going to make sure that people in my community are being empowered and supported. Being transmasculine and nonbinary and queer and black and immunocompromised—there are so many intersections of my identity that play a role in making me who I am. I understand what my community needs, which is why I wanted to provide an affirming and safe space for folks with marginalized identities. (Editor’s note: Allen has been cancer-free since 2017.)

Can you elaborate on the importance of creating that safe space?

It’s hard to exist in a world where you need to be constantly aware of your surroundings in order to stay safe. I know that my brown skin and short hair and masculine look puts a target on my back. People like me have to be careful about making choices about the most mundane things. The obstacles we encounter navigating our daily life can make it difficult to feel like there is a space you will ever fit in.

In my practice as a photographer, it is my job to ensure that I cultivate a comfortable space for queer people to express themselves. The photos I provide accurately capture and represent who they are in this world. I’m their hype person; I’m there to reaffirm how incredible they are.

It’s a tender space where we’re able, on the purest level, to connect human to human. When you strip everything away, all of us are just humans. And we, as humans, simply need to understand that we must support one another in order for anything to get better.

Photos by Jo Allen.