In the forefront, a drying rack of ceramic armadillos at Central Academy’s pottery studio. In the background, students remove slip cast seams before firing.

Writer: Andrea Love

Photographer: Jami Milne

What do the South American three-banded armadillo and the coronavirus pandemic have in common? Artist Jami Milne identified it as self-preservation in a 2022 project titled “Under Pressure.”

In November 2021, Milne was one of 76 individual artists awarded more than $280,000 in American Rescue Plan arts grants distributed through the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs. The one-time funding opportunity was established to help revive the creative industry after the pandemic left many out of work. Grant guidelines specified that the funding needed to be applied toward job development or expenses incurred for a project responding to the pandemic.

In her request, Milne proposed a project based on an idea she had been mulling. “I kept thinking about the idea of being a creature, and that when danger is near, you can just roll yourself in a ball,” she says.

She began obsessively searching the internet for such an animal and found that the three-banded armadillo is the only one of its species that, when sensing danger, rolls itself into a ball, using its outer shell as protection.

At the same time, she was perplexed that this self-protective response by some humans seemed to frustrate others. “It felt like during the pandemic, everyone is doing their best to go into that ball, to go in their family and into protection, but it also felt like people were trying to pull others out of the ball because they didn’t feel it was right. There seems to be this incessant need by society to pull away at these safety nets we’re creating for ourselves,” she explains.

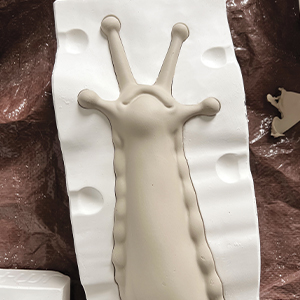

From the ceramic-making process, this image shows an opened snail mold in which casting slip has solidified.

Engaging Others

As a conceptual artist, Milne focuses her work on engaging others in the experience. “I have to create something to say what I feel. There is a sense of me working through a healing process, but I also don’t think I create work that isn’t intended to help someone else process as well,” she says.

Milne, who had no previous experience working with ceramics, wanted to partner with others on the project who could also benefit from the experience and believed teenagers would relate to the complexities of vulnerability and emotional strife.

She reached out to teaching artist Dara Green, the Central Academy pottery teacher. Green teaches functional pottery, like making cups and vases, to freshmen through seniors from Des Moines schools. Milne had previously worked with one of Green’s classes on a photography project and valued that the students came from all around the city. The studio also had a kiln for firing the clay pieces.

Milne’s grant proposal included working alongside the teenage students to create ceramic creatures with casting slip (wet clay), focusing on armadillos and other vulnerable animals and prey like rabbits, birds, snails and fish. Slip casting requires a lot of precision to produce an intact ceramic piece: the right ingredients, proper timing when removing clay from plastic molds, firing in a kiln and careful handling throughout. The artistic vision was to compare the potential cracking of the ceramic by mishandling to forcing a person out of their safe place when they aren’t ready.

Artist and former Central Academy pottery student Sabrina Konchan worked as an apprentice alongside Jami Milne, helping with the casting and installation process.

A pottery student fills an armadillo mold with casting slip during class. Slip casting is the process of filling the mold with slip (liquid clay), allowing it to solidify and form a layer, called the cast, inside the mold’s walls.

Pressed Timeline

Milne was granted only part of the funding she needed for the project and there were delays in receiving the money, so her timeline changed from three months to three weeks. As soon as Milne had the funds, she began practicing slip casting, the first time she’d ever attempted the process.

“Jami was clear that she didn’t have any [ceramics] experience, but she did it anyway,” Green says, adding that part of the lesson for students was not to give up. “One of the many important things they learn in the studio is how to fail, persist and problem-solve, and these are skills they all need to have in life.”

Learning to slip cast was harder than Milne had anticipated, but she says experiencing the mistakes together with the students was part of the art. The students were also receptive to the conceptual learning process. She reminded them that every piece was beautiful no matter how it turned out.

“I really liked how she did not throw any of [the broken ceramic pieces] away,” says Eva Aguero, a 16-year-old Roosevelt student who is in the pottery program. “I liked the model that even if it’s broken, it can still be used.”

Milne checks the casting process of a potter to ensure adequate slip usage.

Safe Space

Milne involved students in every part of the project, including how they would communicate the concept to viewing audiences. She was interested in students’ emotional responses throughout, which Milne and Green had to talk through based on their differing approaches to the studio environment. Green focuses on creating a “safe space” in the studio; she wants students to have a creative place where the stresses of everyday life can be left at the door.

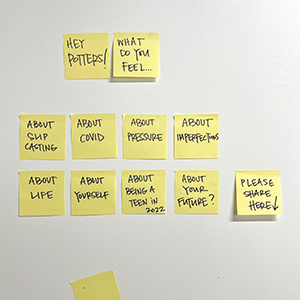

“That was an interesting balance that we needed to have,” Green says. She explained that after a school shooting, some teachers make a point to talk about it and dissect it with their students. She wants her students to know the studio is a place where they can shed all of their worries. So Milne found a non-intrusive form of communicating feelings: Post-it notes.

Milne would post prompts in the form of questions or art display ideas around the studio. Then students would leave Post-it notes to share ideas or feelings anonymously whenever they wanted.

“I had probably 60 Post-its with things like ‘I feel hope for the future,’ ‘I feel terrified,’ ‘I feel vulnerable,’ ‘I feel pressure from my parents.’ There were things that ran the gamut from COVID to just life,” Milne says.

The class ended up with 280 ceramic pieces that were displayed in an art installation Milne and student Aguero created together in Mainframe Studios.

Green says Milne’s approach was the right one for the students because it allowed them the freedom to emotionally participate at the level they felt comfortable with. “I found that more meaningful and authentic,” Green says. “And I’m telling ya, that’s what kids respond to.”

Artist Milne found unobtrusive ways to connect with students’ emotions during the collaboration. She provided Post-it notes for students to share their feelings, if they wished, about the pandemic, their lives and their perceptions about the future.

More Info: To learn more about the project, go to jamimilne.com/under-pressure. To learn more about Central Academy’s state-of-the-art pottery studio, check out this story from the dsm archive.