While Jeff Fleming doesn’t yet have any set plans for retirement, he hopes to work on more of his own art. Here he draws with chalk, a reference to his own artworks, he says, which consist of paintings on canvas that depict chalkboard drawings

Writer: Christine Riccelli

Photographer: Ben Easter

Jeff Fleming grew up in in Ahoskie, a town of about 5,000 people in rural eastern North Carolina that had no art museum and few arts offerings.

But no matter. “Even though [the town] didn’t have theater, ballet or symphony, it still had a lot of culture … [which] broadened the imagination and my desire to know about the rest of the world,” recalls the now 66-year-old Fleming, director of the Des Moines Art Center.

Then when he was around 10, his parents took him to the North Carolina Museum of Art, about two hours west in Raleigh. “It was transformative,” says Fleming, who will retire in April after having the position longer than any director in the Art Center’s history. “The art museum helped fulfill that curiosity I had. It was beautiful. It was complex. It was fascinating. It was wonderful. All the adjectives that you can ascribe to it, the museum did that for me. That has always been what I believe any museum can do and certainly what [the Art Center] can do.”

His enchantment with art led him to major in painting. He earned a BFA from East Carolina University in Greenville, followed by an MFA in 1981 from the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. While in New York, he got a job working in the development department at the Metropolitan Opera, which, he says, “broadened my view of what is possible in terms of making a living” in the arts.

Not only that, but he found he enjoyed administrative work as he made stops at the Spoleto Festival in Charleston, South Carolina, and at Folger Shakespeare Library and the Smithsonian Institution, both in Washington, D.C. “None of these jobs were important, believe me,” he claims, “but one thing always leads to another.”

Specifically, they led in 1983 to the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where Fleming started in audience development and eventually became curator. Sixteen years later, he joined the Des Moines Art Center as a curator, followed by stints as senior curator and deputy director before being named director in 2005.

Over the years, Fleming’s impact has been wide and deep. Artists and board of trustee members praise his strong leadership, not only in running the museum but in engaging the community in an inclusive fashion. “Jeff is such a quiet, powerful force,” says trustee Rosemary Parson, a comment echoed by others. “How he leads and what he’s made happen is awe-inspiring,” including increasing classes and educational outreach; making events and exhibits more inclusive; helping ensure the museum’s financial security; and “peeling back the walls of the secrecy of the museum.”

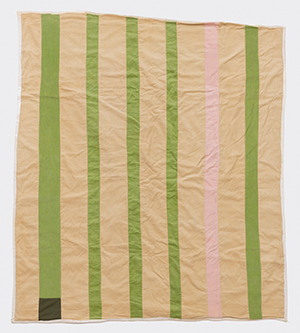

This 3-by-5-foot work by Jeff Fleming may look like a chalk drawing, but it’s actually a painting on canvas.

Groundbreaking Exhibitions

Fleming also has been nationally recognized for the Art Center’s focus on presenting the first one-person museum shows in the United States for younger national and international artists. They include, among numerous others, painter John Currin and multimedia artist Ellen Gallagher, both American; British painter Glenn Brown; and Chinese painter Yan Pei-Ming.

In addition, Fleming presented the first survey exhibitions of the drawings of American Kara Walker, best known for her black cut-paper silhouettes that explore race, gender, sexuality, violence and identity; the ceramics of American Sterling Ruby; and the drawings of German artist Neo Rauch.

“Jeff and his curators have done an extraordinary job building fabulous shows,” says Des Moines-based artist Larassa Kabel, whose work will be part of the upcoming Iowa artists exhibit. “Giving up-and-coming national and international artists their first big museum show is a super smart niche for a midsized museum.”

What’s more, she says, the fact that “you can meet these artists is amazing. You can see their work in person, then go up and talk to them. That’s crazy good, the kind of access that has spoiled us in Des Moines. … The [Art Center] provides so many opportunities to meet interesting thinkers and makers.”

When asked to name his favorite exhibit, Fleming, not surprisingly, looks like he’s just been asked to choose his favorite child. “There are many favorite projects,” he insists, a claim that’s easy to believe given his long tenure and impressive exhibition record. Still, when pressed, he mentions, in addition to Ruby and Walker, designer and sculptor Maya Lin, his first exhibit; and “Black Stories,” a 2020 exhibit that showcased works by Black artists and was co-curated by local artists Mitchell Squire and Jordan Weber. (To read more about the exhibit from the dsm archive, search: “Black Stories” dsm magazine.)

Cultivating the Collection

In addition to exhibitions, the permanent collection has flourished under Fleming’s direction, growing to around 6,000 artworks and becoming more diverse not only in terms of artists but also in forms of media.

For example, ceramics and photography have grown during his tenure, notes board of trustees member Ellen Hubbell. “When I met Jeff close to 20 years ago, photography was just becoming a category in museums,” says Hubbell, who collects photography with her husband, Jim. “Jeff has really ridden the wave on that,” acquiring works by such notable photographers as Gordon Parks and Margaret Bourke-White.

Additional acquisition highlights include works by Sally Mann, Ai Weiwei, Roni Horn, Cecily Brown, El Anatsui and Wangechi Mutu, among many others. “Jeff has a deep, uncanny knowledge of the permanent collection and each artist who’s represented,” says Jim Hubbell, a former board chair. “I’ll listen to the rationale for buying a particular piece and [understand] how and why it adds depth to the collection.”

As with exhibits, Fleming is reticent to name his favorite permanent works. But stroll around the museum with him and the passion of the typically soft-spoken director quickly emerges. He grows animated as he talks about a patchwork quilt by Helen McCloud of Gee’s Bend, a recent acquisition. Quilts from Gee’s Bend, Alabama, are created by a group of women who live or whose ancestors lived in the rural hamlet, many of whom trace their roots back to enslaved people. The quilt is “an extraordinary, craft-based folk work,” Fleming says, explaining that it represents an important visual and cultural contribution to art history.

Another craft-based work Fleming is eager to show off is “Rhino,” a fantasy coffin in the form of a rhinoceros by Paa Joe, a “coffin artist” from Ghana whose hand-crafted casket designs take figurative forms.

Outside of the museum, Fleming’s legacy includes the 4.4-acre John and Mary Pappajohn Sculpture Park, which opened in downtown’s Western Gateway Park in 2009 and today includes 31 sculptures by 25 internationally acclaimed artists, such as Willem de Kooning, Louise Bourgeois, Yayoi Kusama and Keith Haring. The sculptures donated by philanthropists John and Mary Pappajohn represent the biggest single gift—about $40 million—in the Art Center’s history.

This corduroy quilt, one of Jeff Fleming’s favorite recent Art Center acquisitions, was made by Helen McCloud of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. The rural hamlet (population around 200) is known for being the home of notable quilters and their ancestors, most of whom can trace their lineage back to enslaved people. When she was 10, McCloud started learning how to make quilts from her mother, but she took up the craft in earnest after having six children. “We didn’t have no blankets then, so I had to keep making them things,” she told the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting the work of Black artists from the South. Photographer: Rich Sanders. Helen McCloud (born 1938), “Lazy Gal,” 1975; corduroy, 89 x 80 inches; Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections.

Behind the Scenes

Still, in terms of his accomplishments, Fleming says he’s as proud of the less-visible people and things that make up the Art Center as he is of widely heralded projects. For example, after visiting the museum, a Chicago-based curator told Fleming “how welcoming, knowledgeable and approachable” the security guards were, he says. “To hear that was just as [rewarding] as creating something like the sculpture park.” (Read an earlier dsm story about the security guards.)

While Fleming calls his tenure at the Art Center an “extraordinary experience,” he notes that “being at a museum for 24 years is a very long time. That’s one-third of the Art Center’s history. It’s probably time for another point of view.”

When interviewed in the fall, Fleming had no specific plans for retirement, though he says he hopes to work on his own art, which he describes as a mix of drawing and painting. He shows a visitor a work of his that’s hanging in the Art Center’s education wing, an intriguing painting on canvas that depicts a chalkboard. For many years, he didn’t have time for his own art, he says, “but I’m doing a little more now.”

Whatever projects he decides to pursue, he says that he and his wife, Carrie Marshburn-Fleming, plan to stay put. “Our [two daughters] grew up in Des Moines; one lives here and one lives near here,” he says. “This is home now.”