Jordan Weber maintains a house in Des Moines but spends most of his time at his home and studio in New York, where photographer Andre D. Wagner recently shot this rooftop portrait.

Writer: Michael Morain

Take a deep breath the next time you zip past downtown on Interstate 235. If you look at the skyline, you might catch a glimpse of two words — “INHALE … EXHALE …” — on the roof of Mainframe Studios, the big brightly painted building on Keosauqua Way. Seven-foot-tall aluminum letters spell out the words, with back-lighting that slowly pulses to the speed of someone breathing in and out. In . . . and out . . .

It’s a “hopeful visual mantra,” said Jordan Weber, the artist who designed it. “Breathing is essential for calming the mind.”

He hopes the message benefits everyone who sees it, but he made sure to point it northwest toward the Oakridge Neighborhood, the low-income housing development where more than half the residents are kids and two-thirds are immigrants and refugees from two dozen countries. The artist’s message is a reminder that “maintaining a meditative breath can be healing when facing challenges, including discrimination.” The sculpture carries extra weight after George Floyd’s last words, “I can’t breathe,” in another mostly white Midwestern city became a rallying cry for the Black Lives Matter movement.

As part of its mission, Mainframe elevates the role artists play in the community. The new rooftop beacon does that, literally, in an area where Black culture thrived before bulldozers demolished parts of Center Street in the 1960s under the banner of urban renewal. Weber’s installation sends an even stronger signal when you consider the skyrocketing career of the artist himself, who grew up north of downtown, started drawing by copying Saturday morning cartoons and now has a resume stacked with a Guggenheim Award, a Harvard fellowship and residencies with Yale and the Pulitzer Arts Foundation. He’s received major commissions across the country and exhibited work last year at the Venice Biennale.

“I feel like I’ve infiltrated the Ivy Leagues,” he said. “But it took some hustle, like being Black or brown in Iowa.”

Weber specializes in unusually large public artwork on the scale of architecture and even landscape architecture. Most of his recent projects focus on social justice and the environment in areas where people of color have been, as he put it, “pushed and pulled around in a small space” through generations of redlining and other forms of systemic discrimination.

He recently designed a community garden in north Minneapolis near a shingle factory and scrap metal yard, in a predominantly Black neighborhood where rates of cancer are twice as high as in the general population, according to the Star Tribune. Asthma is nine times as prevalent. “In extremely ghettoized areas,” he said, “there’s no difference between violence against the land and violence against Black, brown and Indigenous bodies, especially in the Midwest.”

A decade ago, Weber was just starting to get a foothold in the art world, with exhibitions at Moberg Gallery here in Des Moines and similar spaces in Omaha and Kansas City. When a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, shot and killed Michael Brown in the summer of 2014, Weber drove down to join the protests and returned to Iowa with a new determination. He bought an old Ford Crown Victoria on Craigslist, painted it to look like a police car and filled it with invasive plant species and dirt he’d collected from Ferguson. It caught the attention of a curator who invited him to Crenshaw, a mecca for Black art in Los Angeles.

“That’s when everything blew up,” he said.

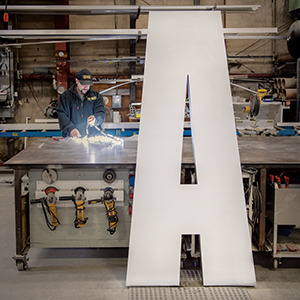

Troy Kenney, a fabricator at Chesnut Signs on the city’s northeast side, tinkers with the lights that will illuminate the giant “A” and other letters in Jordan Weber’s rooftop sculpture at Mainframe Studios. Photo: Duane Tinkey

Artistic Roots

Weber and his wife, Julia, own a house near Roosevelt High School but spend most of their time in New York, raising two daughters on the Upper West Side. He’ll turn 40 in September.

His first memories of making art were in grade school, when he sketched Spider-Man and his favorite X-Men from TV. His mom had studied art at Drake University and made sure he always had some crayons and markers close at hand.

In third grade, at Woodlawn Elementary School, he made a poster about Jesse Jackson, who saw it during a visit to the school and kissed him on the forehead. Years later, Weber posted a video of the encounter on Instagram (@jordan_j_weber) for all “the homies” who thought he was making it up.

Weber went to Hoover High School and distinguished himself on the basketball team. A while later, he worked a stint for the Boys and Girls Club at the former First Christian Church, near Drake, and McCombs Middle School on the south side, where he helped kids express themselves through art. He showed them some of his own paintings and helped them design a mural.

“He was absolutely amazing with the kids,” his supervisor, Mary Lou Warner, recalled. “He used his art and his fascination with art to connect with them in a way I hadn’t seen in 20-some years.” She encouraged him to pursue an art career and has watched it take off. “I can’t imagine the lives he’s touched along the way,” she said. “I’m just incredibly proud of him.”

In 2013, Weber decided to stencil some jumbo Louis Vuitton logos on a boarded-up house at 15th Street and University Avenue. A neighbor pulled up to caution him — or shoo him away — until Weber explained the idea behind it, that he wanted to add an ironic touch of luxury to the last place anyone would expect it. (You can still find the “Louis Vuitton Crack House” on the Greater Des Moines Public Art Foundation’s website.)

Two years later he had more explicit permission, and a legit commission, to paint the Pop Art mural at 309 Locust St. in a prominent spot next to Cowles Commons. By that point, he’d received a fellowship from the Iowa Arts Council and had started to adapt his street art for galleries and museums. The Des Moines Art Center bought one of his Pop Art collages and a mixed-media sculpture from his “Chapels” series, which includes soil and chunks of marble from the site of the church in Charleston, South Carolina, where nine African Americans were murdered during a Bible study in 2015. That piece was part of the museum’s 2020 exhibition “Black Stories,” which Weber co-curated with the Ames artist Mitchell Squire, before the Black Lives Matter movement took off nationwide.

“From early on, it was obvious that the conversation [Weber] was having with his art was very important, very potent, very powerful,” former Art Center director Jeff Fleming said.

In St. Louis, Weber built an open-air chapel that incorporates lines from a poem by Cheeraz Gormon: “We remember what it means to love and how to put ourselves and each other back together.” In Omaha, he built a greenhouse modeled after the childhood home of Malcolm X. And last summer, in Detroit, he planted a whole “regenerative forest” to create a healing green space in a historically Black neighborhood that bumps up against a Stellantis-Mack assembly plant.

Fleming said Weber’s artwork follows in the tradition of the New York artist David Hammons, whose multimedia work focuses on African American culture and history, and Rick Lowe, who transformed a cluster of dilapidated row houses in one of Houston’s oldest Black neighborhoods into a thriving art colony. “That type of work — investigating the background and bringing it into the future — that’s very much a part of what Jordan is doing,” Fleming said.

Rebuilding Community

“Investigating” is a good way to describe Weber’s approach to the project at Mainframe. After the studios’ former director, Siobhan Spain, invited him to propose a public artwork for the site, he dug into the history of the Center Street neighborhood between 15th Street and Keo Way. Between the early 1900s and 1960s, the area flourished with Black-owned grocery stores, hotels, restaurants, the state’s first cosmetology school and jazz clubs that hosted legends like Josephine Baker, Count Basie and Ella Fitzgerald.

The construction of Keo Way displaced several buildings in the 1920s, and the MacVicar Freeway (I-235) pushed out other property owners in the 1960s. The five-story concrete building that houses Mainframe was built in 1983 to house a data center for Northwestern Bell, followed by a call center for Qwest and then CenturyLink.

“It’s critical to acknowledge the past, how things came to be, and to re-imagine how things could be in the future,” said Mainframe’s current director, Julia Franklin, who stepped into the role in December.

She said Weber’s installation opens up “a way to make amends” and signals that everyone belongs in the studios and the public programs they host. Mainframe is set up as a nonprofit — the largest of its kind in the country — to safeguard against gentrification, so artists of all kinds can afford to rent space even if property values rise in the surrounding neighborhood. Its mission statement includes a goal “to advance equity” in addition to providing opportunities in the arts.

Siobhan Spain’s sister, Molly Spain, designed the abstract mural, “Critical Mass,” that wraps around the Mainframe building. She teamed up with Weber early on to figure out how their projects could complement each other. “We drove all around,” she said, “looking at the building from different hilltops.”

Sometimes, when Weber takes a step back to examine his own career, he seems a little surprised by how far it’s taken him. “What I’ve accomplished, being from Des Moines, it all started with drawing in a small apartment complex on the north side,” he said. He’s grateful for his family and friends, who have supported him “from the foundation to the scaffolding to the shingles on the roof.”

But he knows his success is rare. Since he “made it through,” as he put it, he wants to lift up others along the way.

Several years ago, he worked with Oakridge to memorialize one of its residents, Yore Jieng, who was 14 years old when a stray bullet cut his life short in 2016. Weber met with many of Jieng’s friends and neighbors to create a fitting tribute, a mural on a basketball court where Jieng often played, and another mural on a nearby building.

But Weber went a step further, Oakridge president and CEO Teree Caldwell-Johnson said. “The time Jordan spent with the kids — just educating them and talking about public art and the importance of representation — that made a huge difference in how they viewed not only the artwork itself but the ideas and concepts and, really, the magic they brought to the overall project,” she said. Weber even hired some of the Oakridge kids to help paint the murals, so they could feel a sense of ownership every time they passed by.

Caldwell-Johnson remembered Weber from his days on the Hoover basketball team and said she was both surprised and impressed by his transition to art. “It became clear to me that it was his calling,” she said.

These days Weber often says that his artwork is informed by trauma. It’s sparked by injustice but offers a glimmer of hope. As he put it, “I want to create work that inspires some sort of healing” — one step, even one breath, at a time.

Rendering of Water Curia. Image: Jordan Weber and Hartman Trapp Architecture Studio

A Proposal for Water Works Park

Jordan Weber’s design for a proposed sculpture at Water Works Park takes the form of a circular pavilion, open to the sky. Its walls have boulders at the base, medium rocks in the middle and sand near the top.

It’s like “a giant soil sample,” said Graham Gillette, a Des Moines Water Works trustee. The form suggests how the facility filters water for use throughout Central Iowa.

The project’s other source of inspiration was the late Bill Stowe, the water works CEO who championed the fight for clean water until he died in 2019, after a bout with pancreatic cancer. “Bill was a good friend of mine,” Gillette said, “so I want to stick his name on something because it would have made him mad.”

“He would have hated that,” agreed Amy Beattie, Stowe’s wife.

So instead of creating a big plaque with Stowe’s name — or a statue of his likeness, with his famous white mane — his family and friends decided to honor his legacy by promoting something he cared about: environmental education. They originally considered building an outdoor classroom that included some sort of artistic component.

But when they met with former Des Moines Art Center director Jeff Fleming, “he said you have it backwards,” Gillette recalled. “Instead of building a classroom that’s pretty, what you need is an art installation that can function as a classroom.”

Fleming introduced the team to Weber, who took to the idea right away.

“When you think about environmental justice and environmental apartheid, Iowa is at the epicenter of that,” Weber said, noting the state’s role in the Gulf of Mexico’s “dead zones” caused by agricultural runoff. “Iowa is one of the culprits.”

Pollution and climate change tend to disproportionately affect communities of color, Weber said, especially in Midwestern cities where historically Black and brown neighborhoods are relegated to floodplains or areas with fewer trees.

Weber likened the pavilion to a small coliseum or a stadium, and he calls it the “Water Curia,” borrowing a Latin word for “assembly” or “dialog.”

The project team enlisted Drake University’s School of Education to develop on-site signs and an accompanying curriculum to help teach the general public and visiting school groups about water quality and ecology. As Beattie put it, “We want to make sure this is a place that’s used to push forth the ongoing dialog about water use.”

“Water Curia” is planned for a site between the Lauridsen Amphitheater and Fleur Drive. At press time, the project team had raised about $900,000 toward the goal of $1.1 million for the sculpture’s installation. A second campaign will fund its maintenance and evolving educational materials.

Sharing the Spotlight

Since Jordan Weber’s artwork focuses on community, he made a point to offer some shoutouts for other local artists of color. Here are a few he singled out, in his own words.

Robert Moore

He’s been painting for only five or six years, and he’s doing extremely well, dissecting the actual business of the national arts scene. It’s really impressive to see him flourish. It’s wild that he’s been able to do that in such a short time. (Read more about him in “Raw and Real,” published in dsm in November 2020.) Photo: Duane Tinkey

Swan Youth Ballet Project

The Swan program is part of the nonprofit SEEDS, which Dontreale Anderson and Sarah Jae founded to help BIPOC youth use the arts for self-expression and empowerment. They’ve really stepped up over the last few years to fill a gap where some other youth nonprofits left off. They’re bringing in national artists and dance artists to lead programs with kids, and they’re producing some incredible results. Since they’re still struggling to find adequate funding, I really want to highlight them, first and foremost, because they’re doing the work and picking up the slack. Photo: Rajaa Camp-Bey of 7Mindz Productions

Billy Weathers

I was in Ferguson and then Minneapolis when George Floyd was killed, and Billy was holding it down and leading the charge with other individuals here in Des Moines. He’s stayed in the pocket of frontline activism through music and other forms of direct action through his nonprofit, the B. Well Foundation, which has given funds to Des Moines Public Schools and other organizations. (Read more about him in the profile “The Many Sides of Billy Weathers,” published in dsm in March 2021.) Photo: Janae Gray

Jill Wells

Jill is the one doing all the Black empowerment murals around Iowa. She’s helped me with quite a few projects and has always been just the most gracious, loving, supportive Black female artist in the city for almost a decade now. She’s surpassed my skill and talent with murals, which is one reason I don’t do murals anymore. Her murals speak about Blackness, and she does that beautifully. (Read more about her in “Making Art Accessible to All,” published in dsm in November 2022.) Photo: Janae Gray